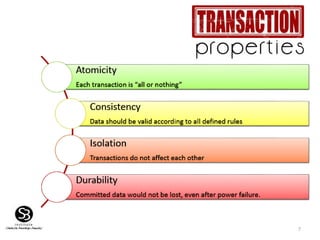

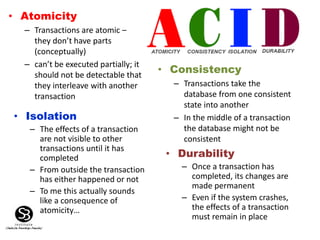

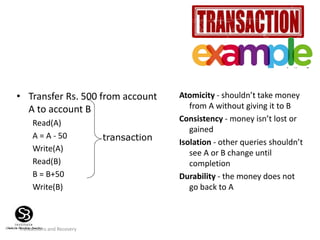

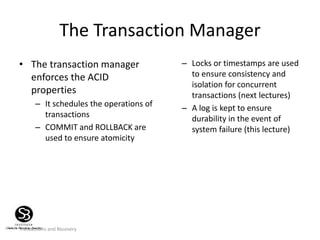

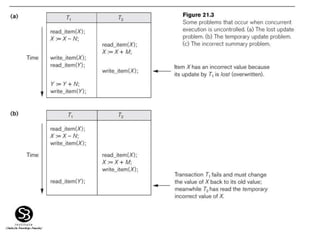

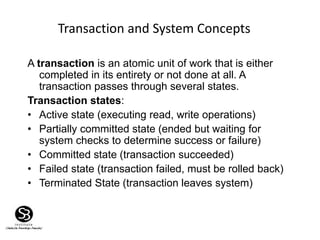

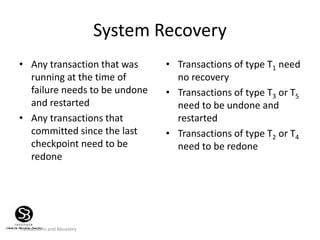

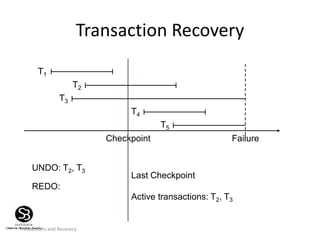

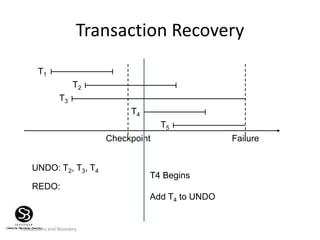

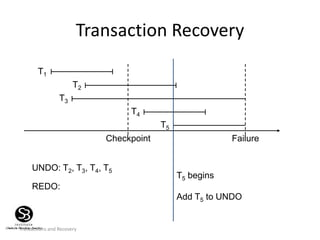

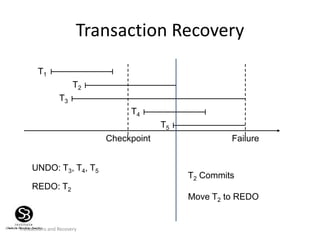

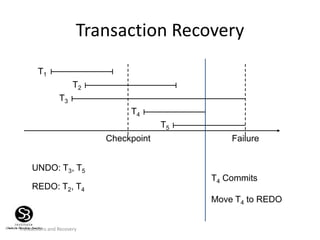

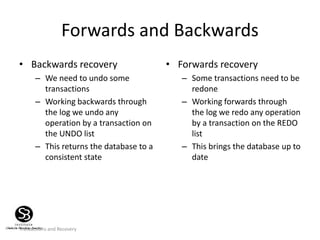

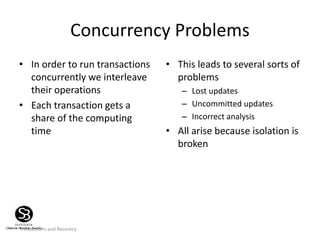

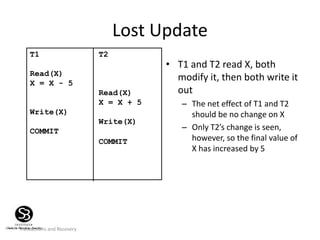

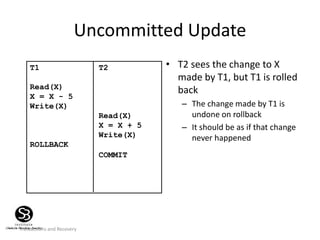

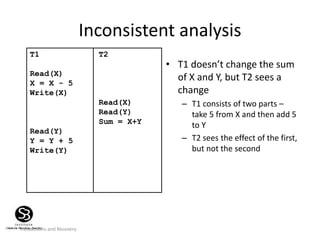

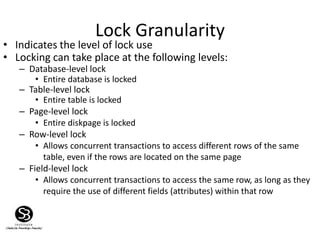

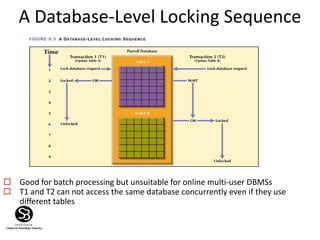

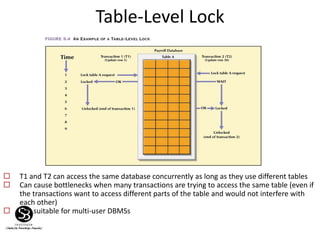

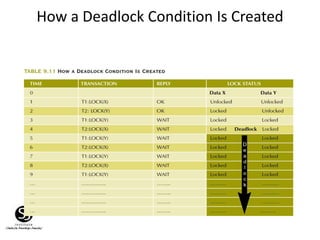

Transactions are defined as actions that read from or update a database, requiring atomicity, consistency, isolation, and durability (ACID properties). The document discusses challenges in managing transactions, including concurrency control issues like lost updates, and methods such as locking and optimistic approaches to ensure database integrity. Recovery techniques are emphasized to handle failures and ensure consistent state restorations through mechanisms like transaction logs and checkpoints.

![58

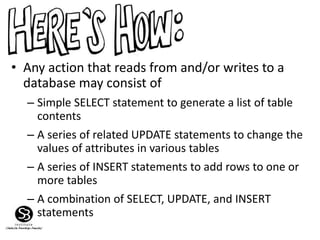

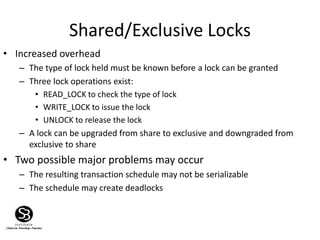

Schedules

• A schedule is a list of actions from a set of

transactions

– A well-formed schedule is one where the actions of a

particular transaction T are in the same order as they

appear in T

• For example

– [RT1(a), WT1(a), RT2(b), WT2(b), RT1(c), WT1(c)] is a well-

formed schedule

– [RT1(c), WT1(c), RT2(b), WT2(b), RT1(a), WT1(a)] is not a well-

formed schedule](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tranasactionmanagement-190926153954/85/Tranasaction-management-58-320.jpg)

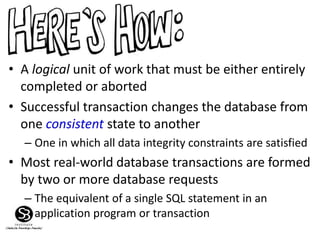

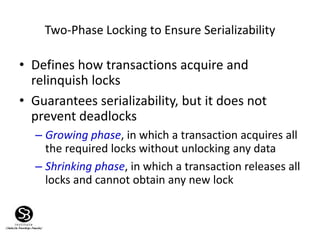

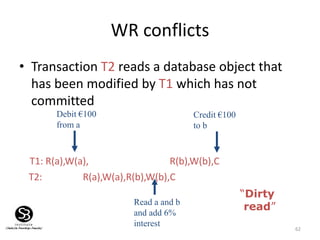

![64

WW conflicts

• Transaction T2 could overwrite the value of an

object which has already been modified by T1,

while T1 is still in progress

T1: [W(Britney), W(gmb)] “Set both salaries at £1m”

T2: [W(gmb), W(Britney)] “Set both salaries at $1m”

• But:

T1: W(Britney), W(gmb)

T2: W(gmb), W(Britney)

gmb gets £1m

Britney gets $1m

“Blind

Write”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tranasactionmanagement-190926153954/85/Tranasaction-management-64-320.jpg)