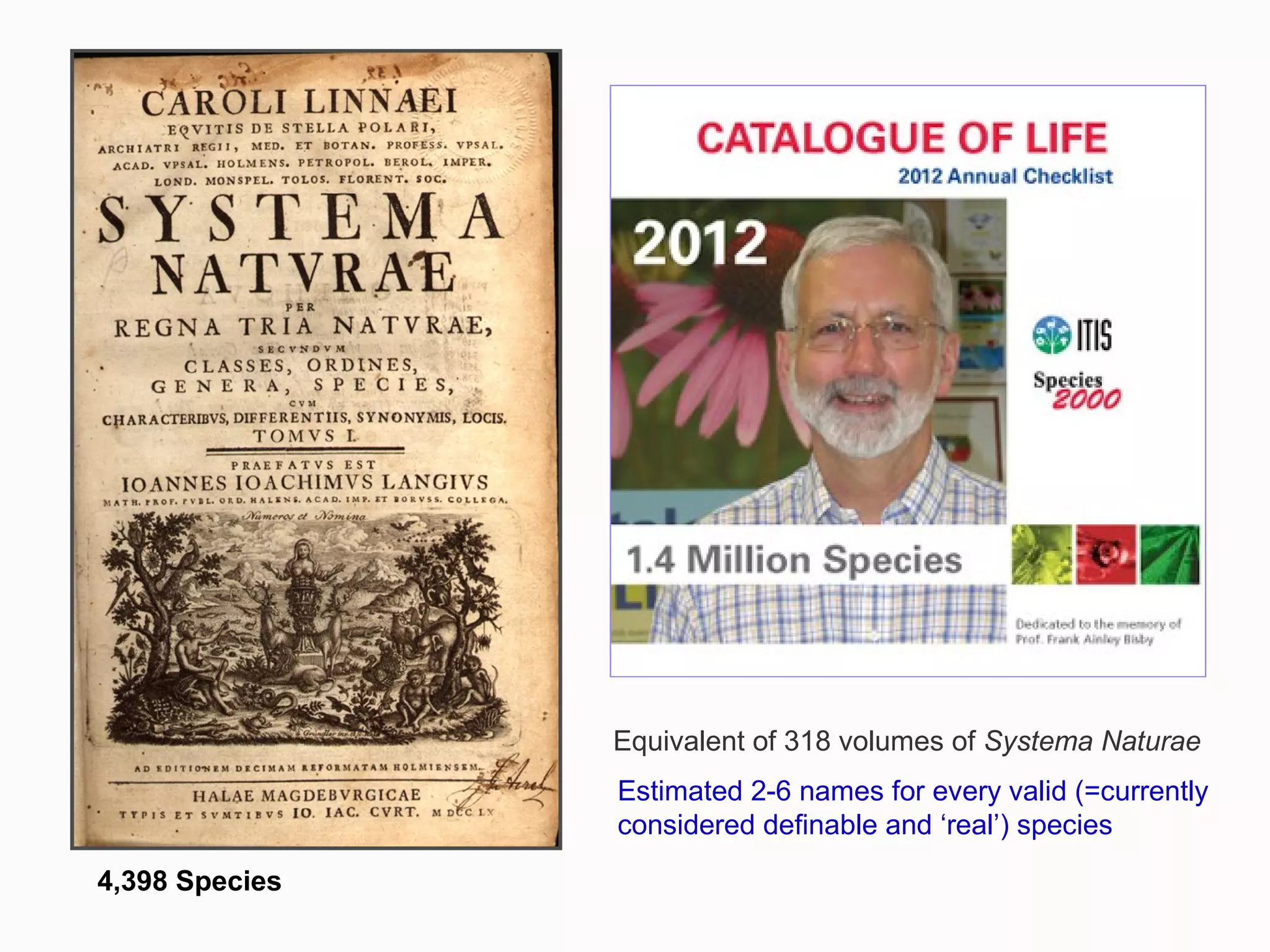

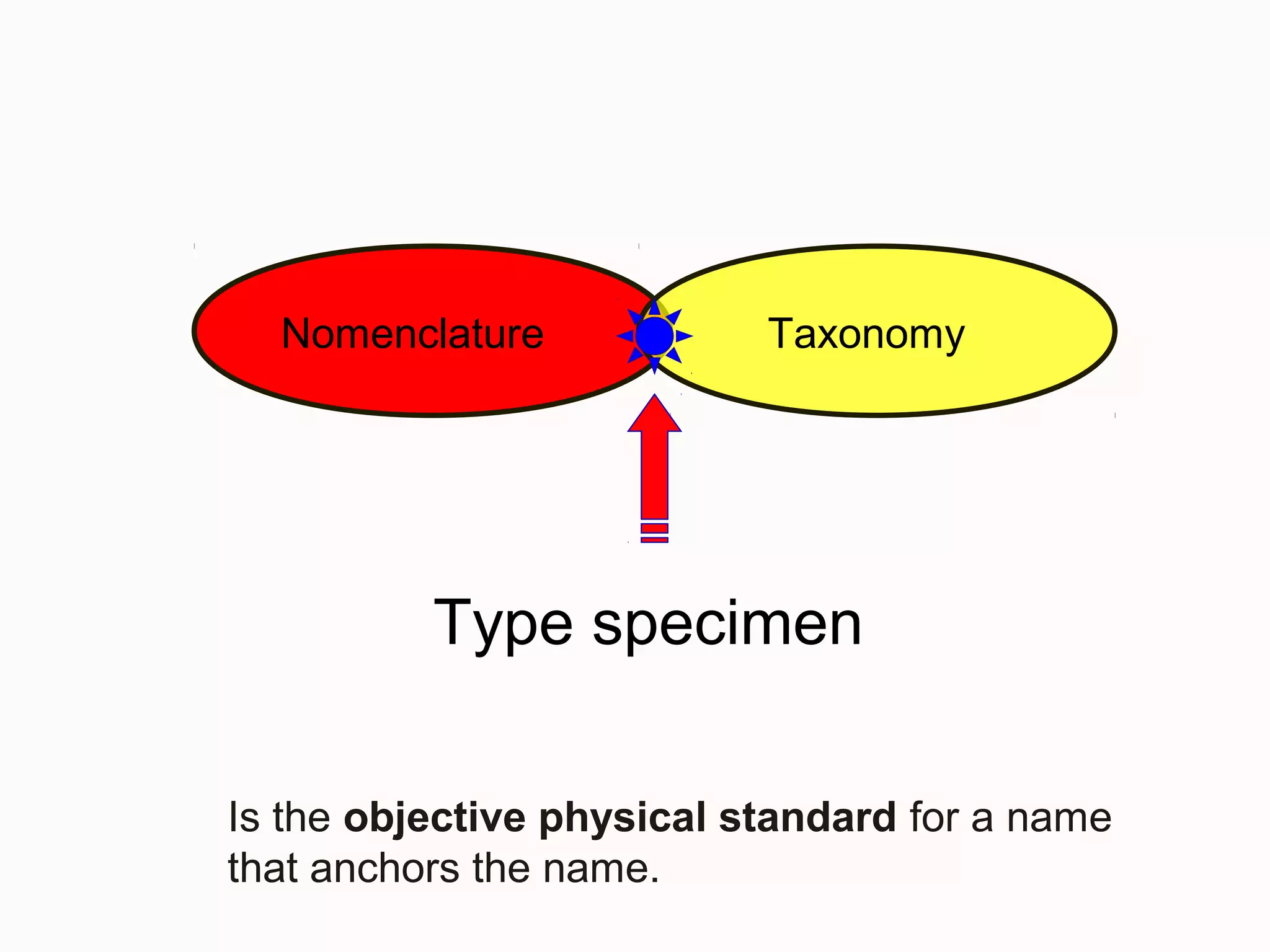

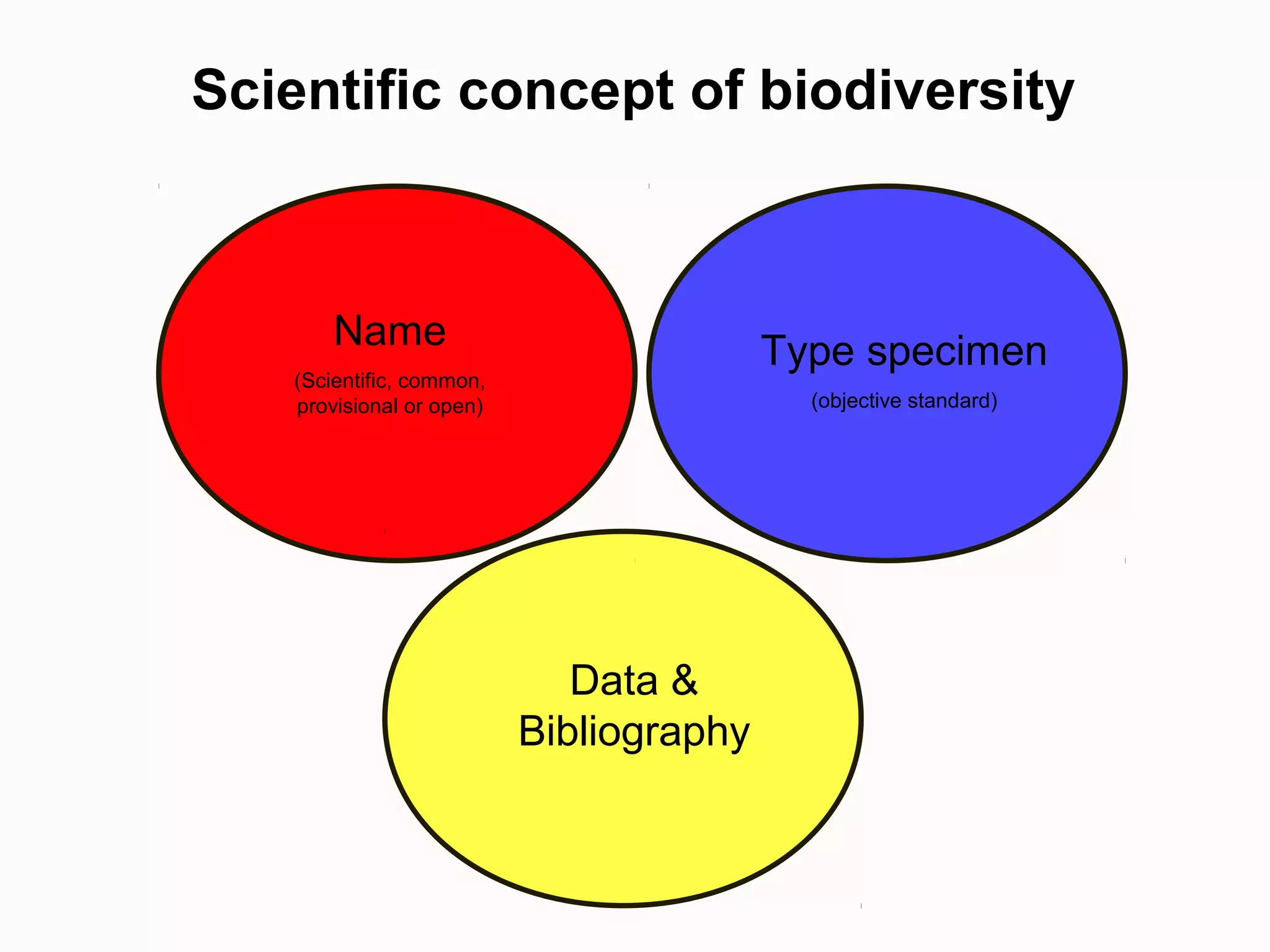

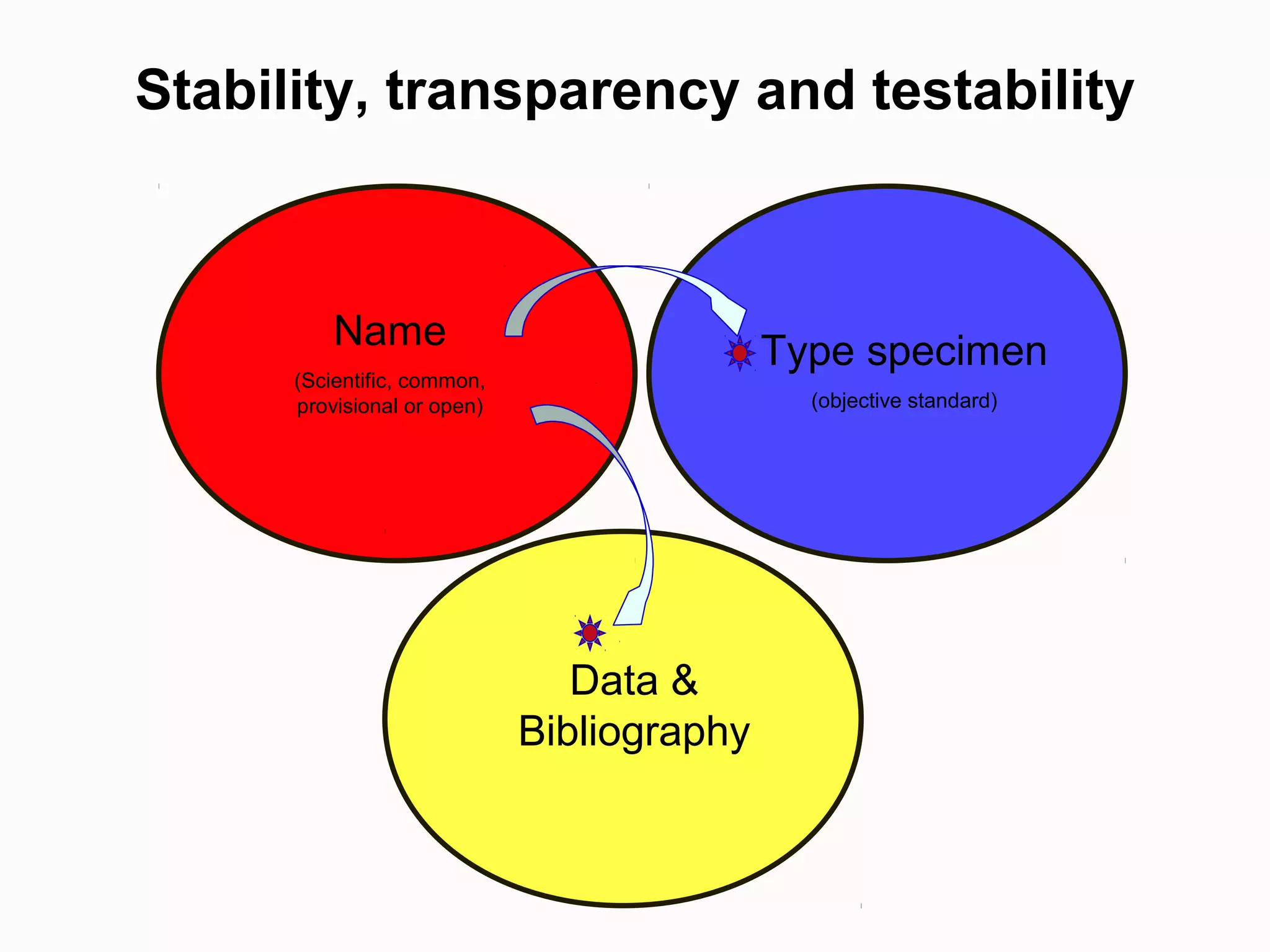

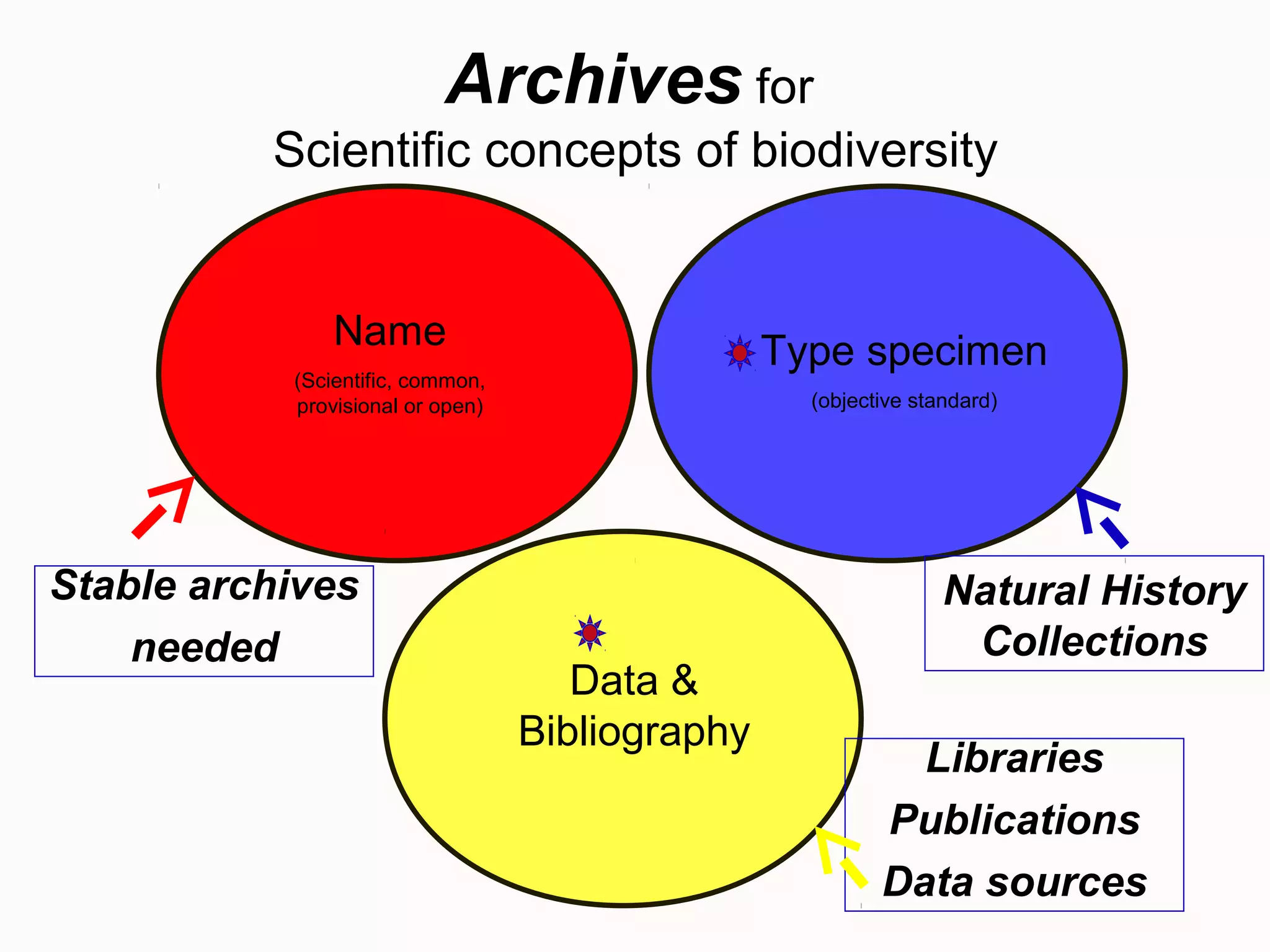

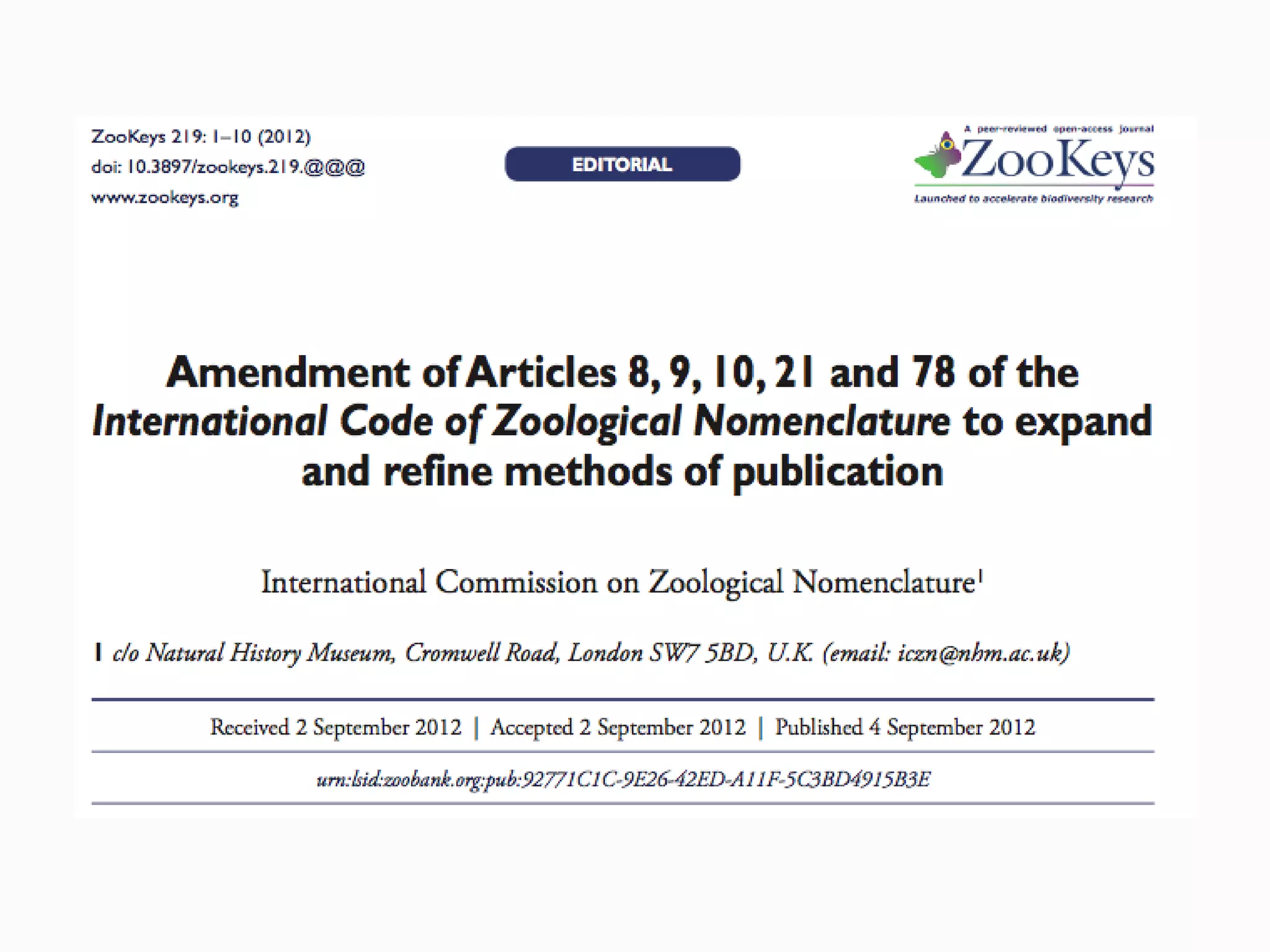

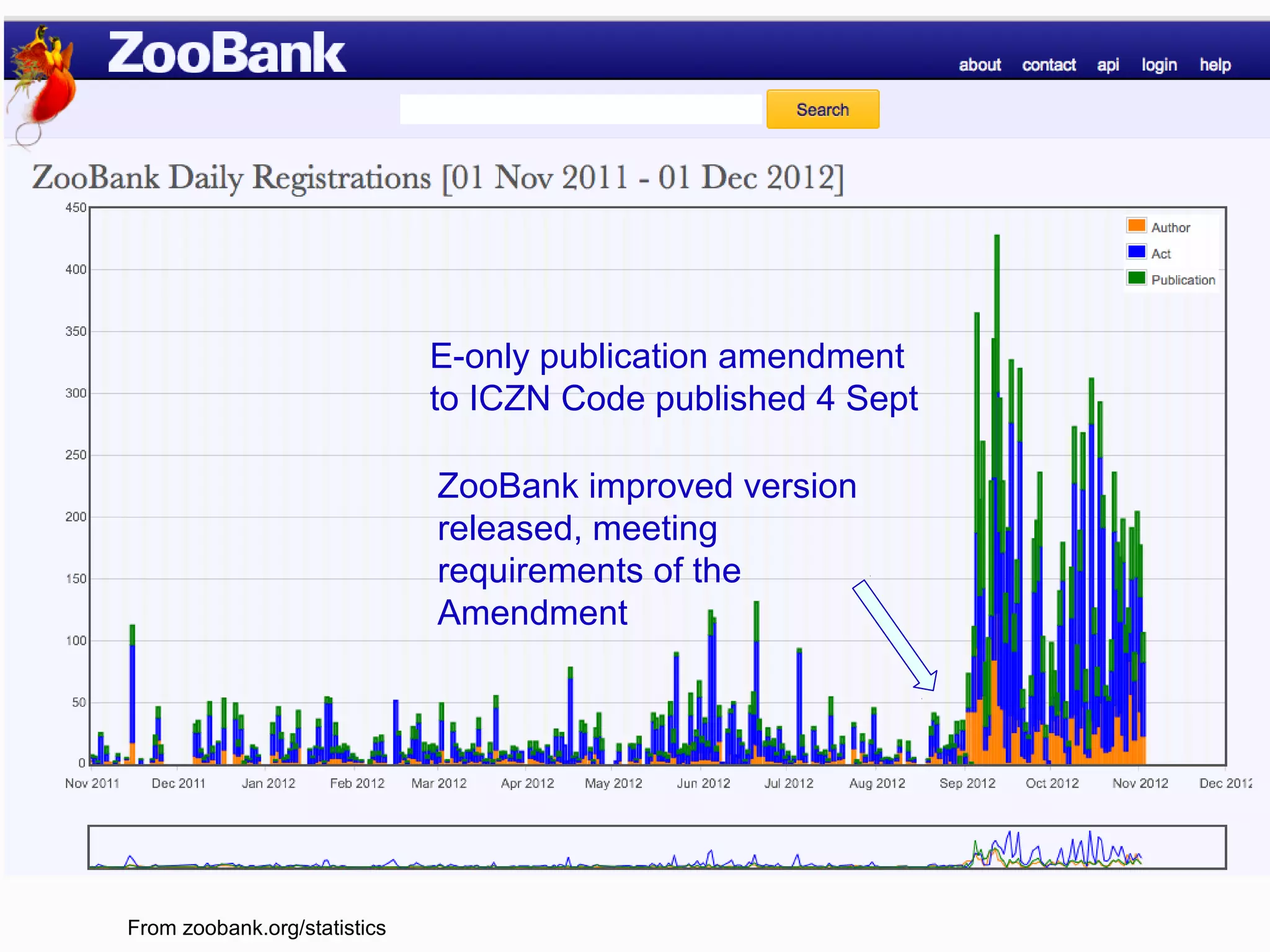

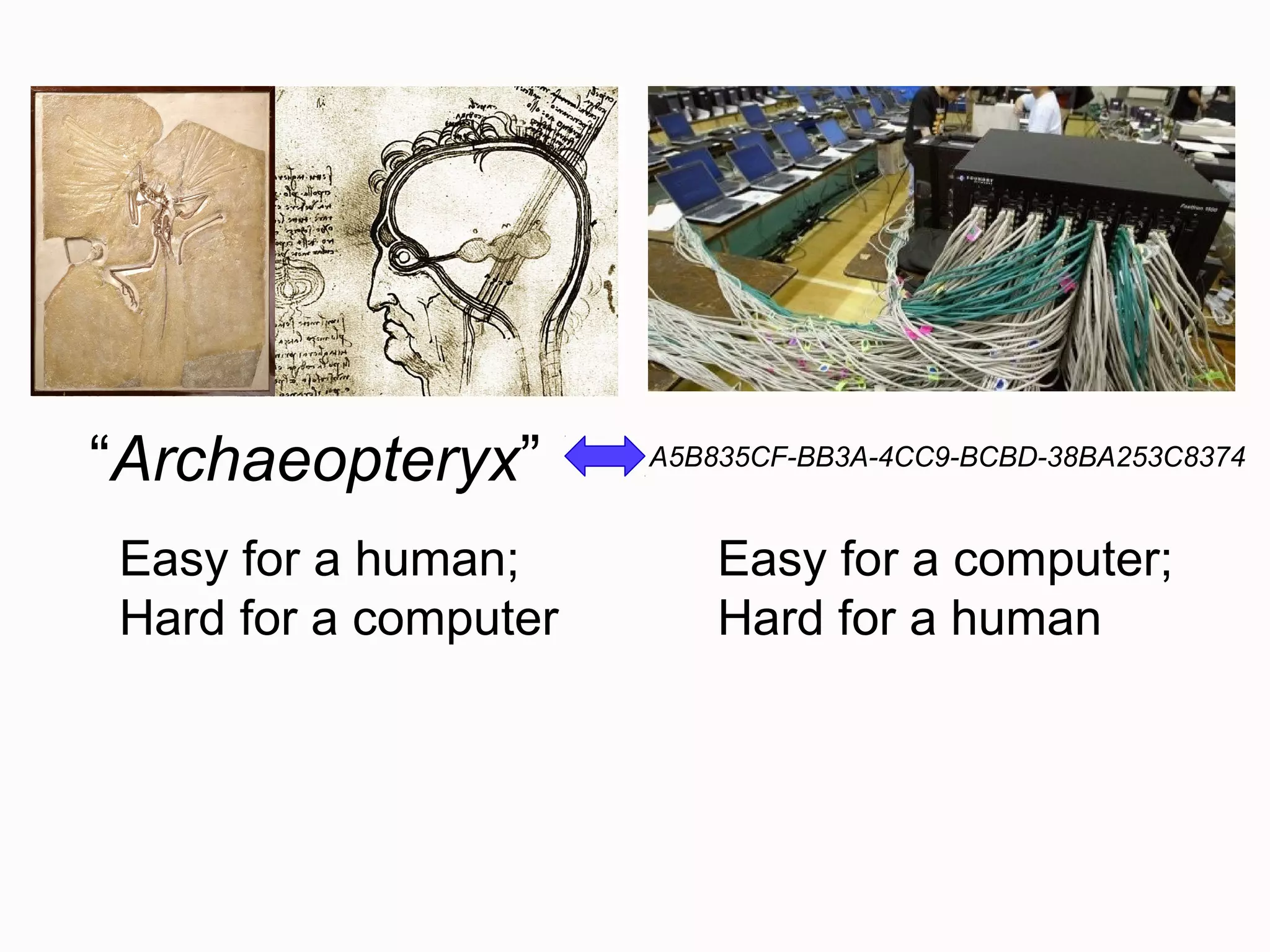

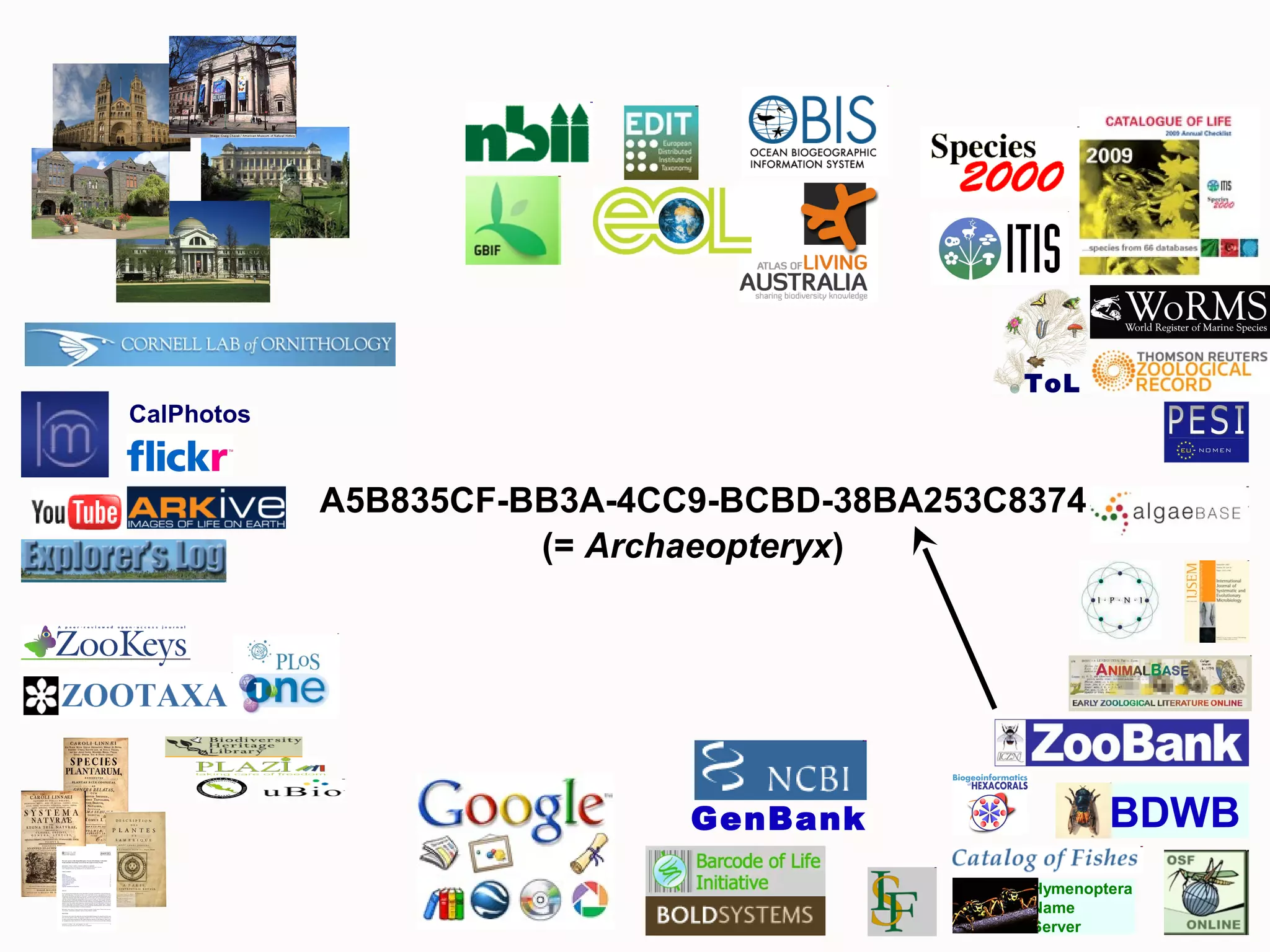

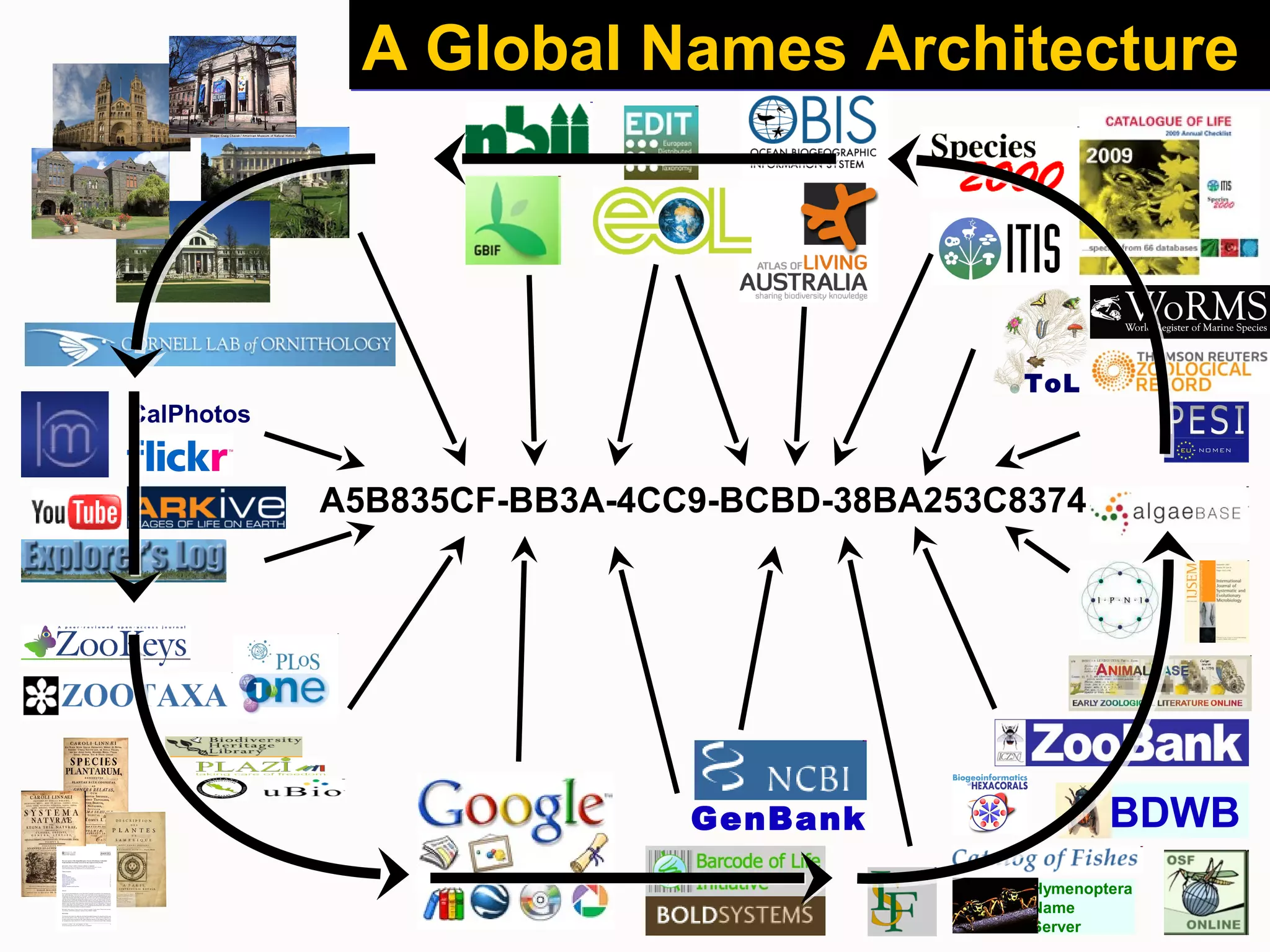

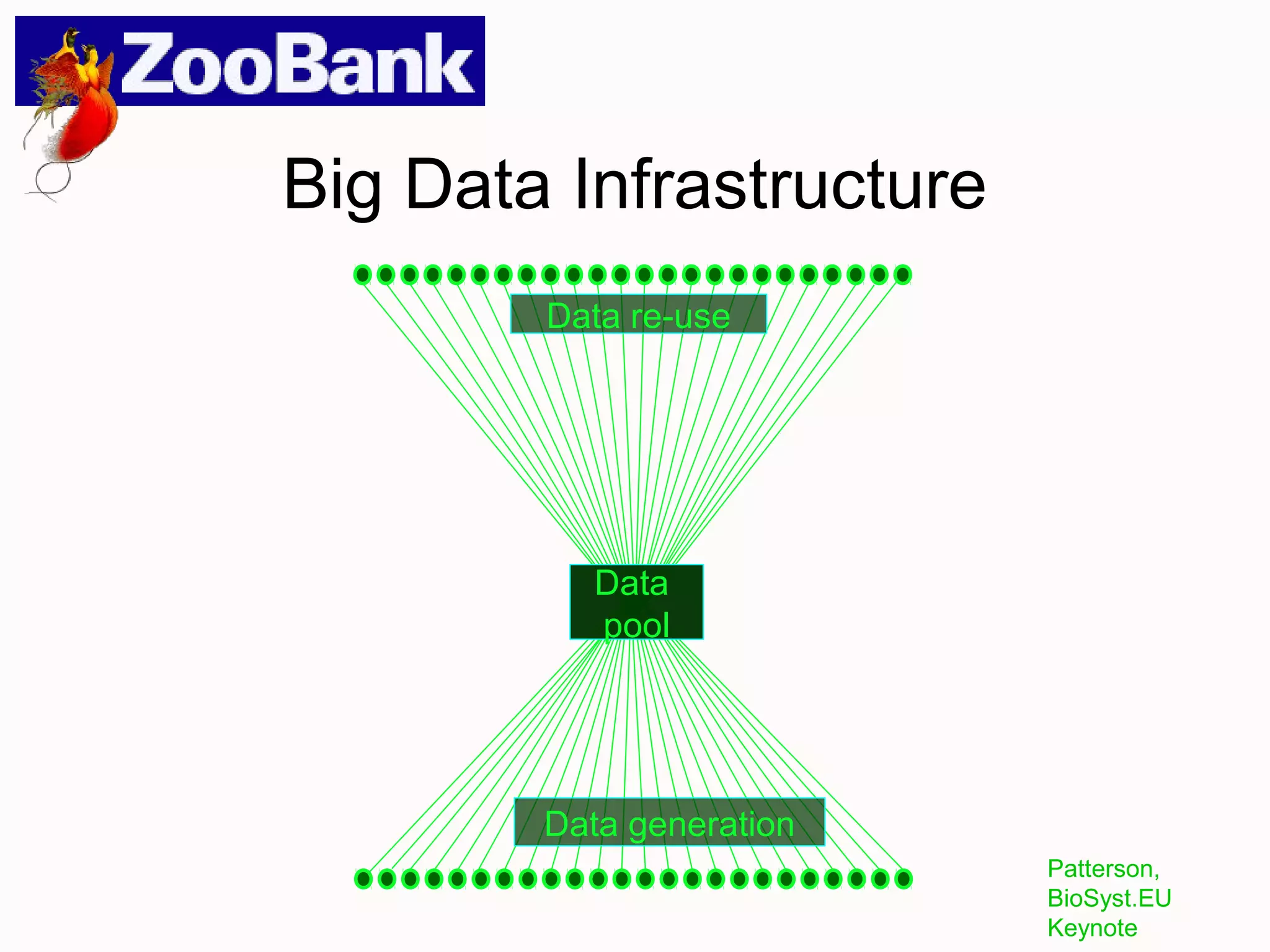

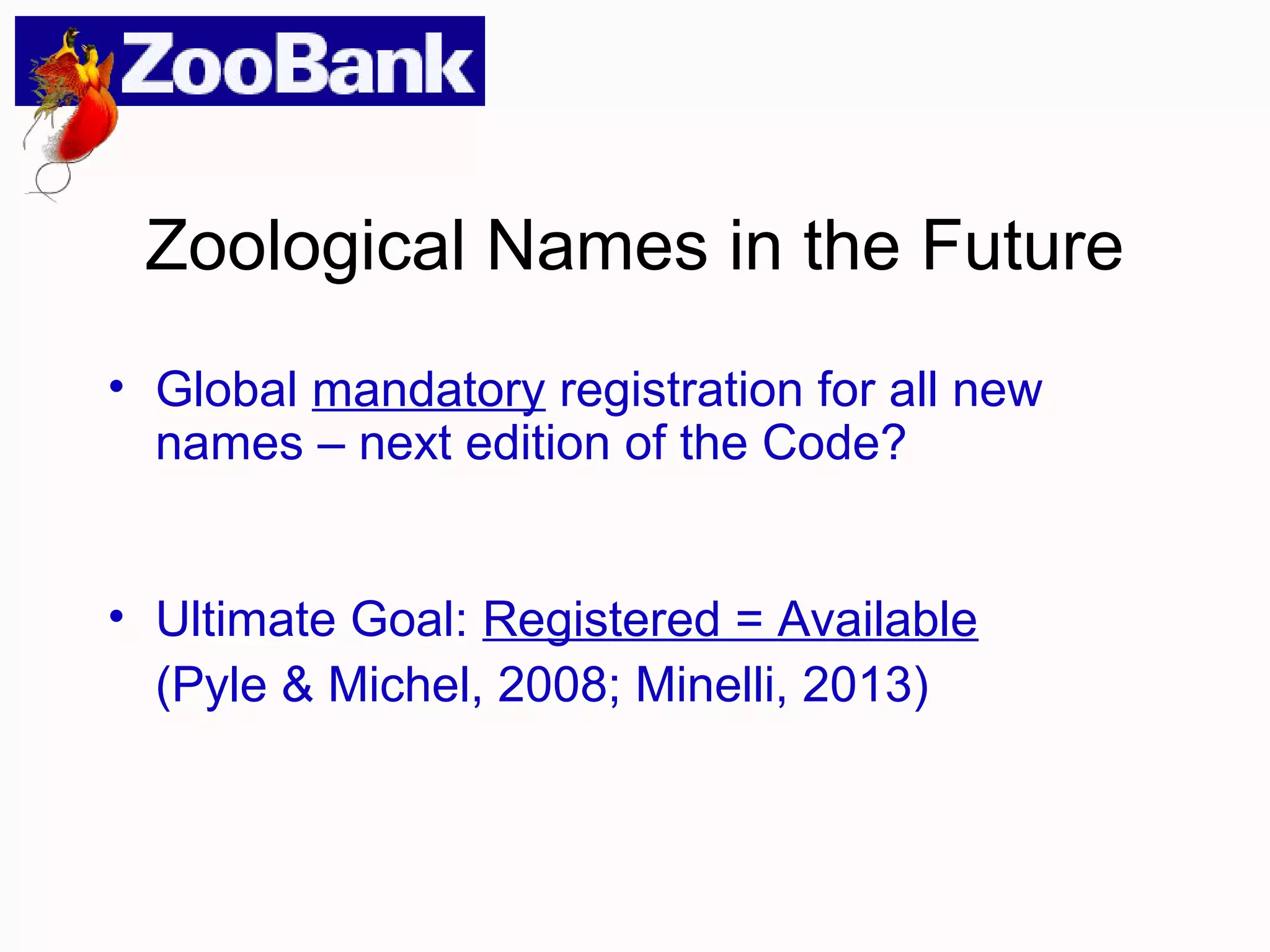

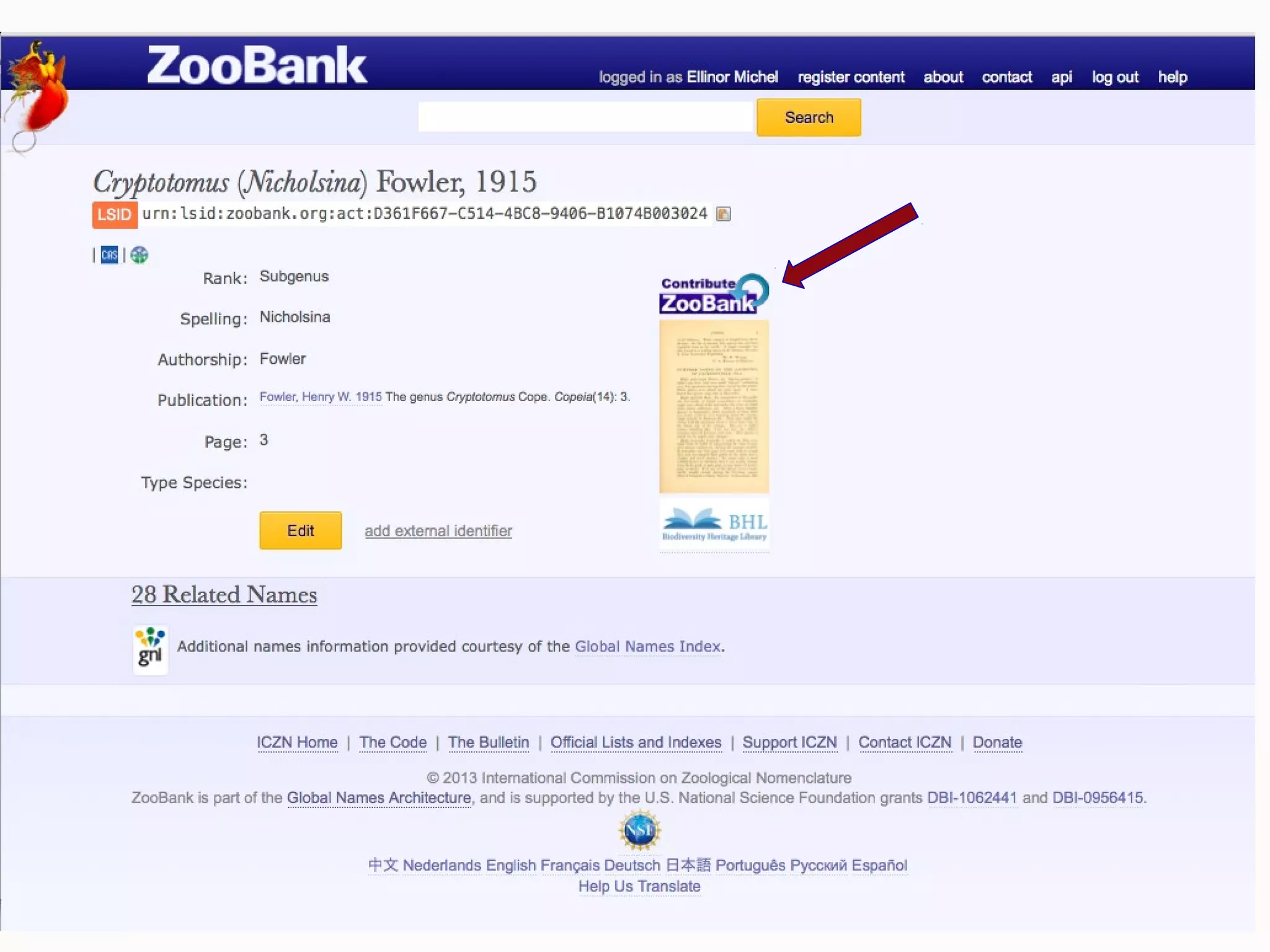

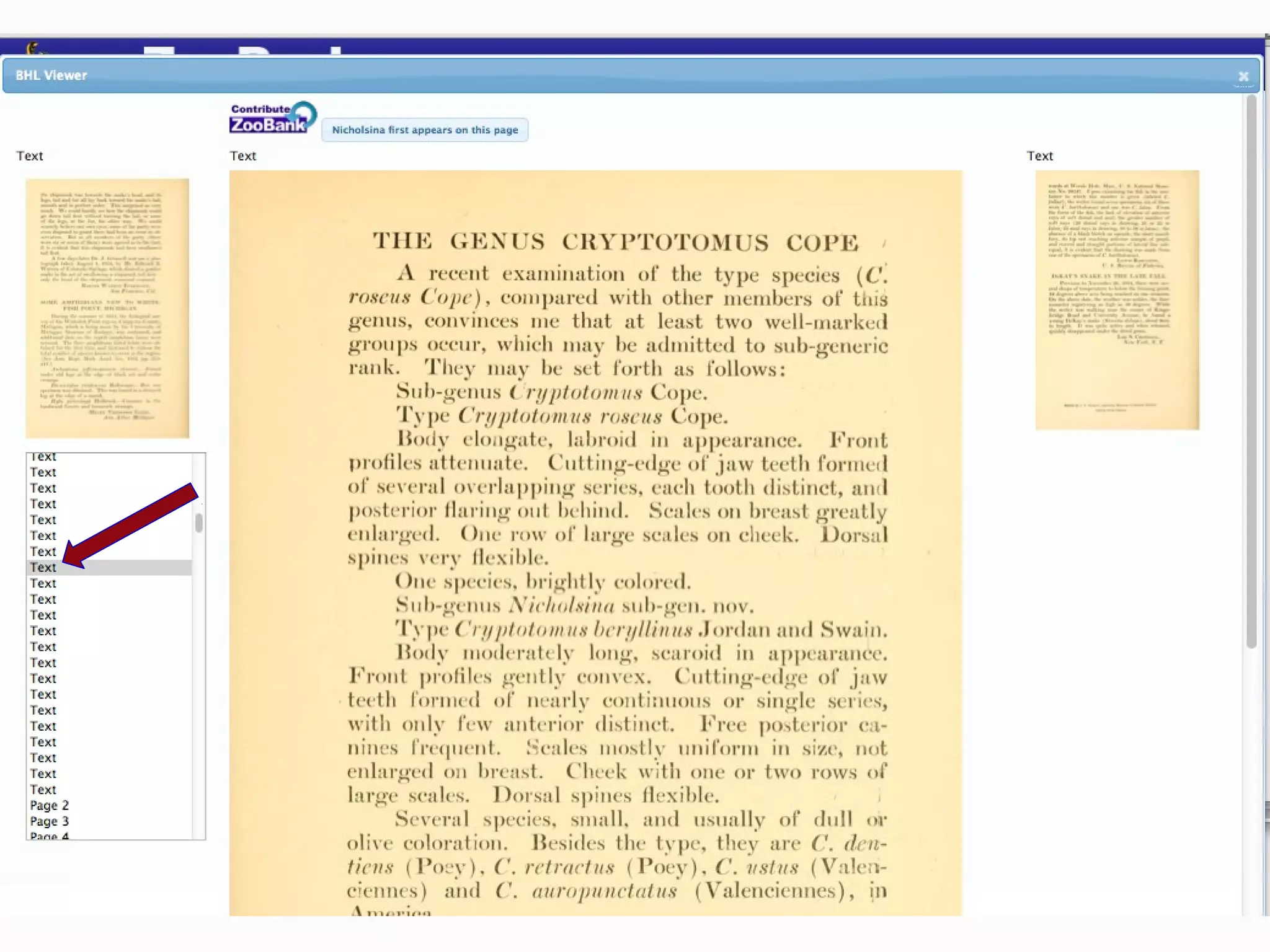

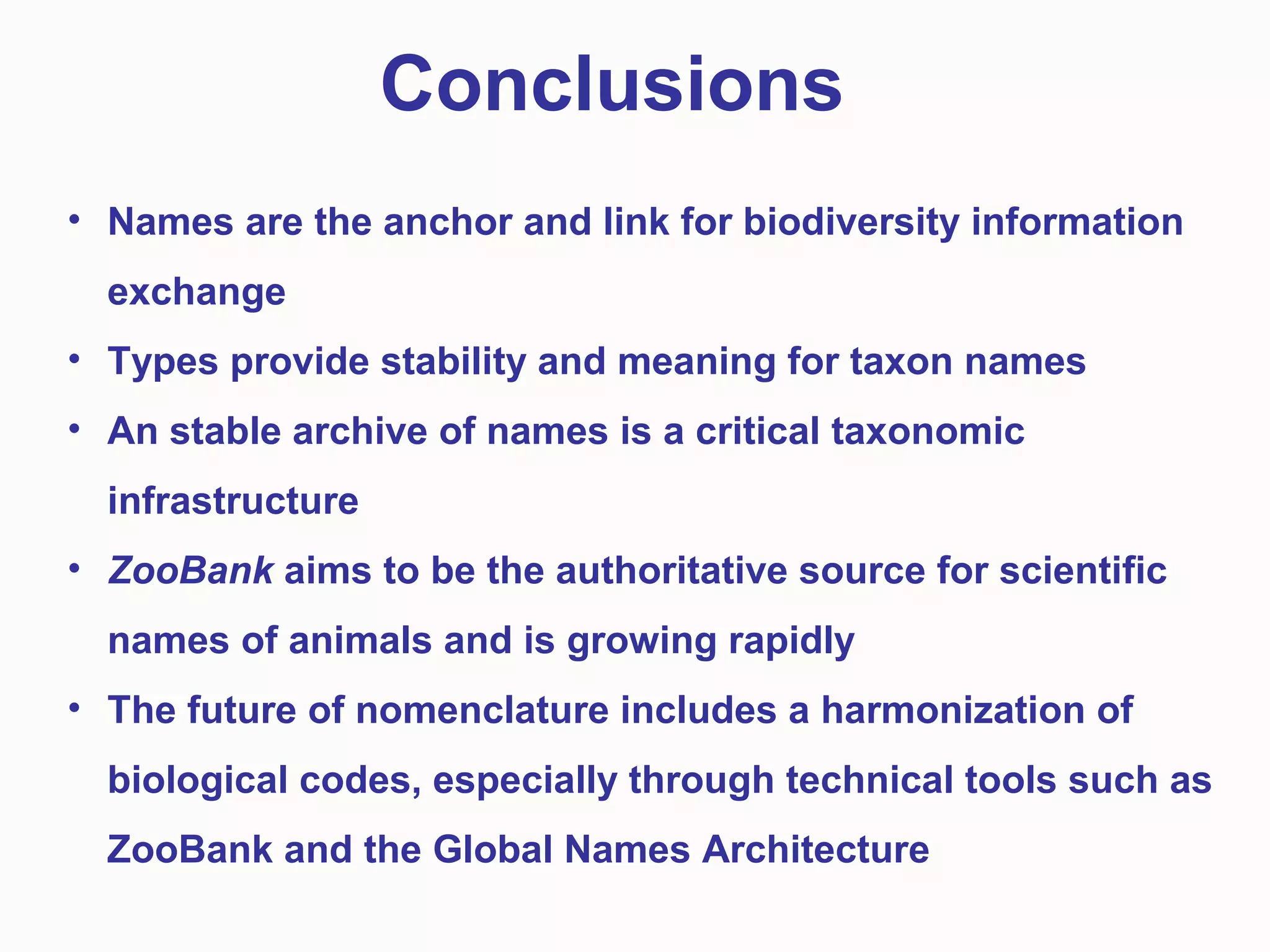

This document discusses the future of scientific naming for animals and the challenges involved. It notes that scientific names serve as links between past and current knowledge about a species. While millions of animal species are estimated to exist, only a small fraction have been named so far. The document advocates for registering all new and existing scientific names in ZooBank to create a global standardized nomenclature system and infrastructure. This would help link names to taxonomic and bibliographic data across different databases for improved information sharing and analysis of biodiversity.