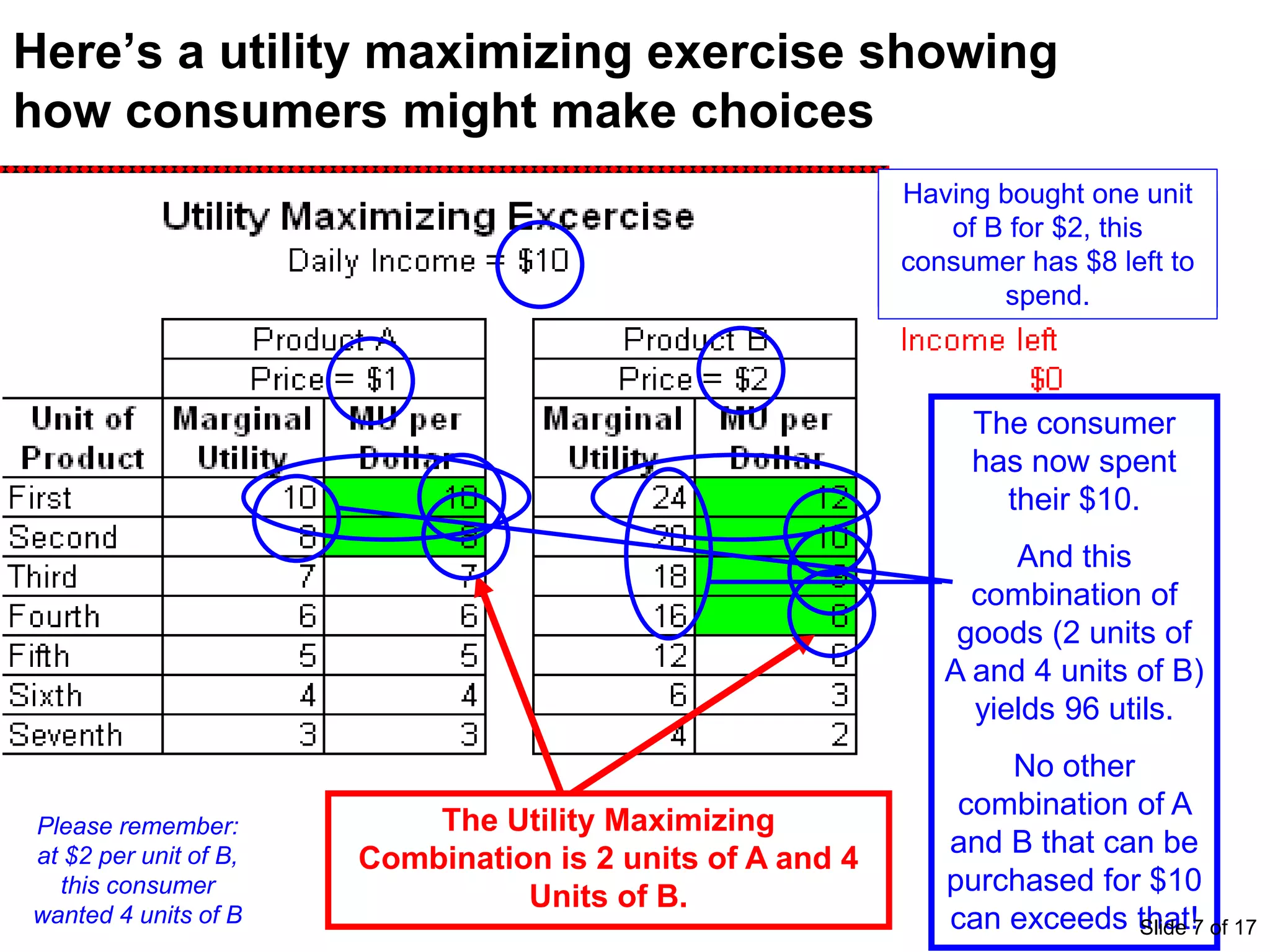

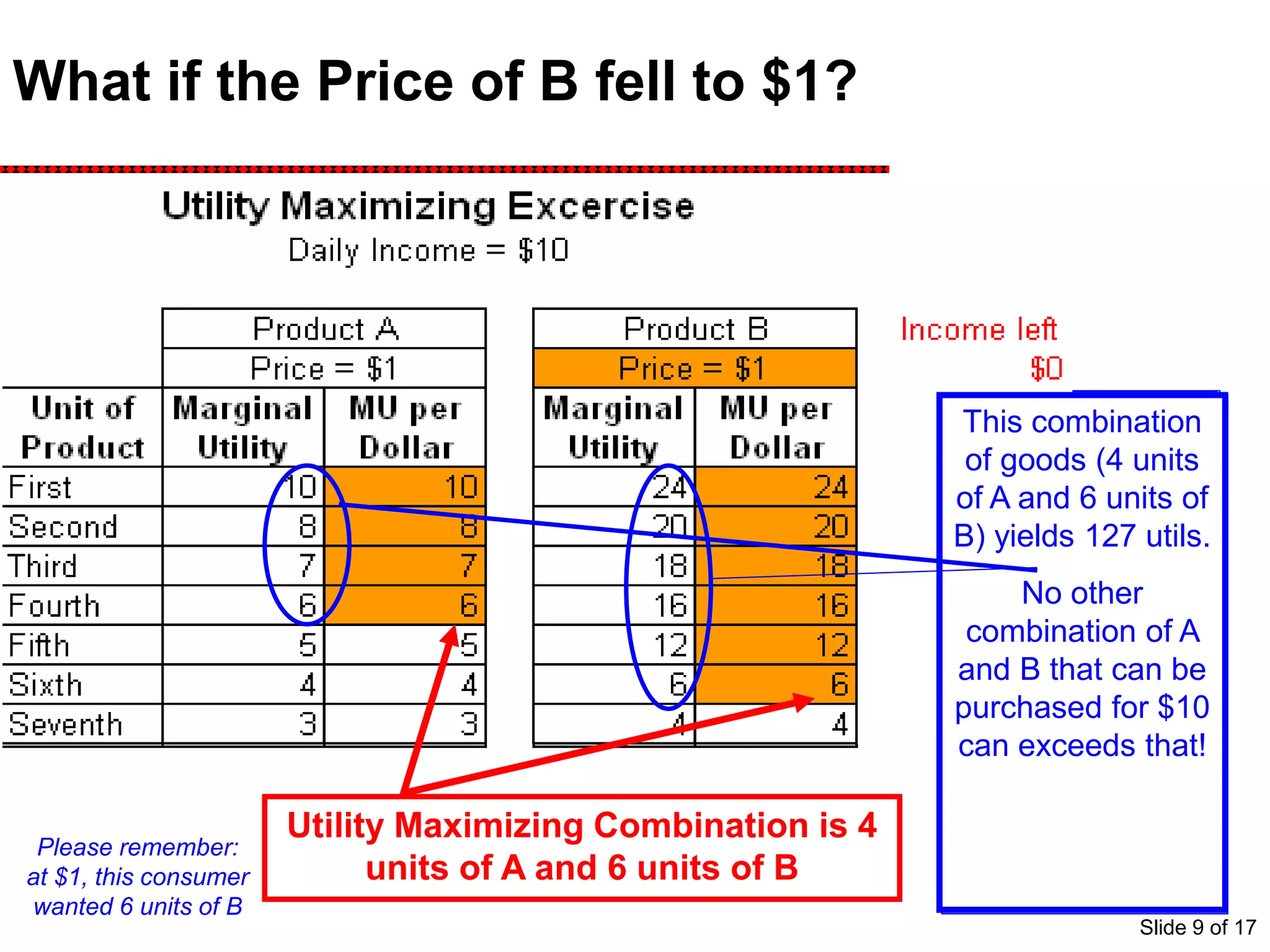

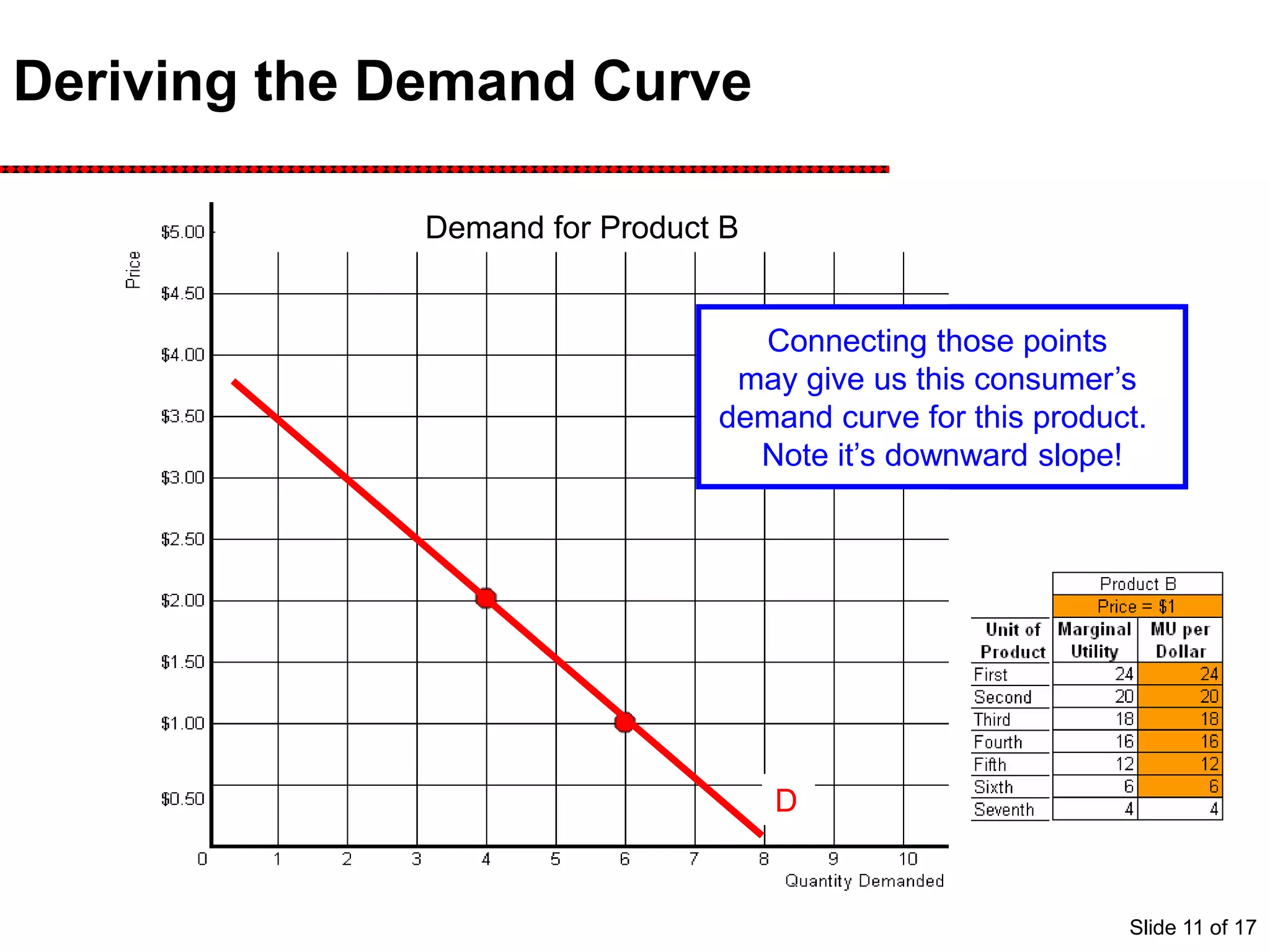

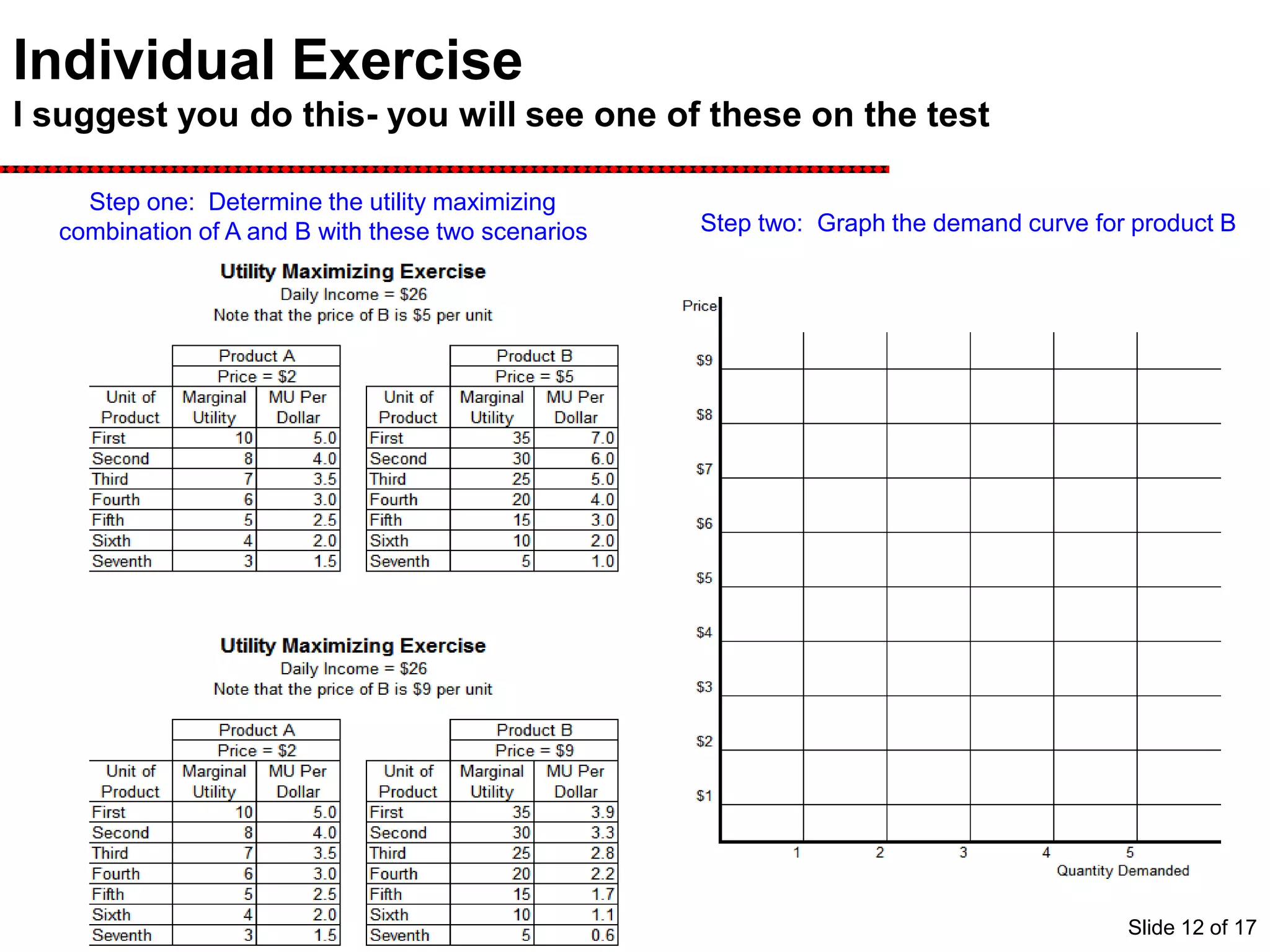

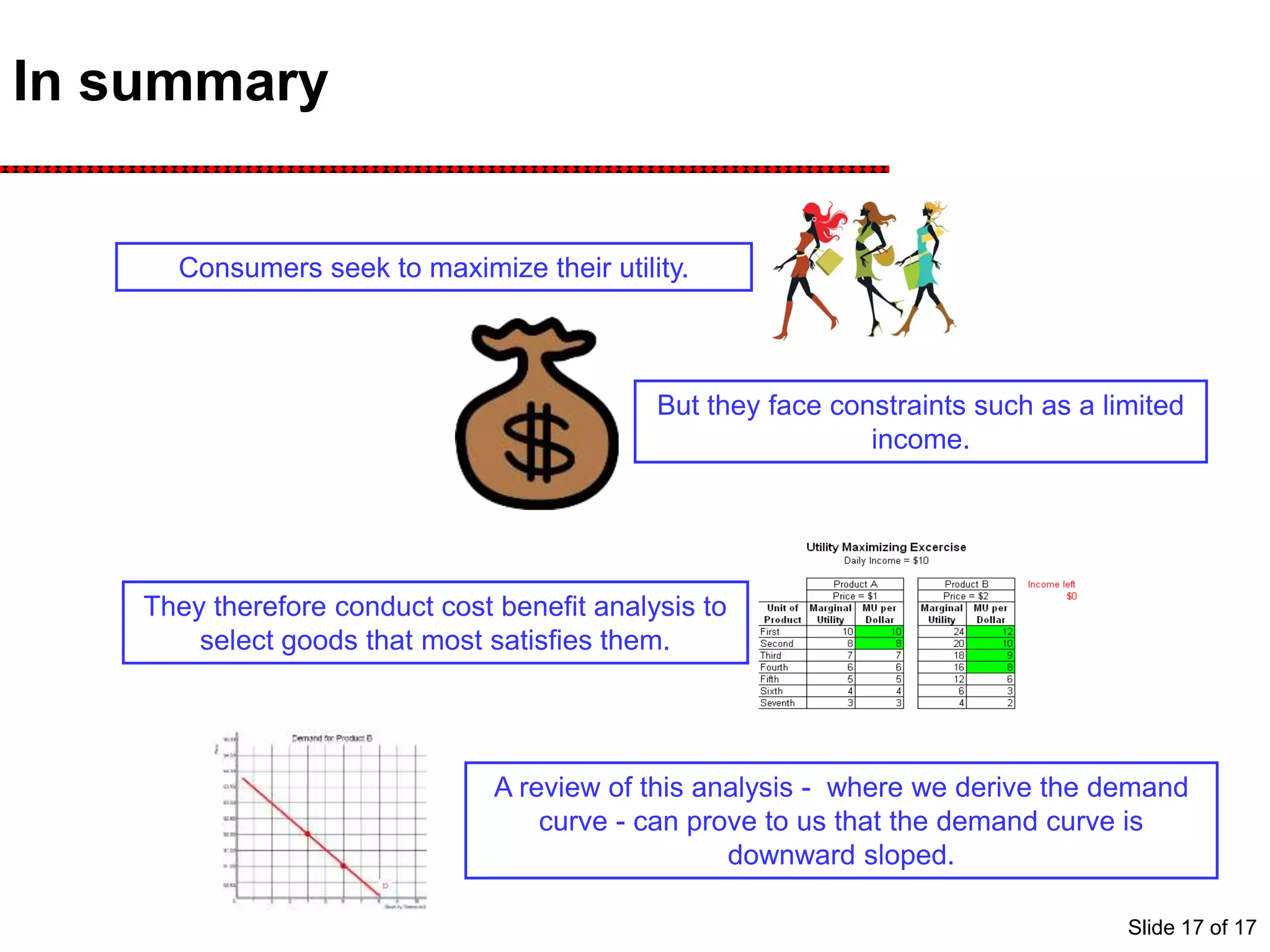

The document discusses the analysis of consumer choice and how to derive the downward sloping demand curve. It introduces concepts like marginal utility, the law of diminishing marginal utility, and utility maximization. An example is used to show how a consumer would make choices between goods A and B under different price scenarios to maximize their utility within their budget. By connecting the quantity chosen at different prices, the individual's demand curve for good B can be plotted, showing a negative slope as predicted by the law of diminishing marginal utility and the substitution and income effects.