This document discusses the evolution and functions of the temporal lobe. It notes that the temporal lobe is larger in humans compared to apes, with increased gyral white matter and interconnectivity. This supports the development of social cognition abilities in humans. The temporal lobe, and specifically the amygdala, plays a key role in social processing, interpreting facial expressions and eye gaze. Damage to the temporal lobe can cause a variety of cognitive, behavioral and neurological symptoms, depending on whether the left or right lobe is affected. Syndromes like Geschwind-Gastaut syndrome and Kluver-Bucy syndrome may result from right temporal lobe lesions.

![83

© Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2016

M. Hoffmann, Cognitive, Conative and Behavioral Neurology,

DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-33181-2_5

Temporal Lobe Syndromes

5

Evolution of the Temporal: Some

Pertinent Details

This is one of the few cortical regions that are larger

in size in humans in comparison studies with apes.

Overall there is a relative white matter increase but

with a specific gyral white matter increase as

opposed to core white matter which is not rela-

tively increased. Gyral white matter increase as

opposed to core white matter is thought to mediate

much greater interconnectivity, enabled by the

short association fibers [1]. In comparative analy-

ses, amongst modern humans, relatively wider

orbitofontal cortices, enlarged olfactory bulbs, and

larger and more forwardly placed temporal lobe

poles are evident, consistent with social brain

development [2]. The amygdaloid complex is par-

ticularly concerned with the social brain develop-

ment such as social cognition, coalitions, and

emotional regulation. Another unique human

development is the relative enlargement of the

basolateral nucleus of the amygdaloid group of

nuclei (lateral, basal, accessory nuclei). This is also

consistent with the general surge in interconnectiv-

ity of the temporal lobe association cortices [3, 4].

The Evolutionary Importance

of the Social Circuitry

and the Social Brain

Hypothesis

The importance of social cohesiveness and the

challenge of the polyadic relationships are con-

sidered to be a major if not key drivers of

increasing human brain size (Fig. 5.1) [5]. With

the temporal lobe a central component of social

processing with the amygdala in particular it is

not surprising that some significant human

enlargements have been reported in this part of

the brain. Human gaze and eye contact are

important initial contact modes and ascertaining

eye gaze direction of a conspecific or other

human and its monitoring are functions of supe-

rior temporal lobe [6]. The amygdala also has a

key role in interpreting social facial signals

from the face. A functional MRI study revealed

that during eye contact (and also without eye

contact) the direction of gaze activated the left

amygdala indicating a general role in monitor-

ing eye gaze. This differed from the right side

where only during eye contact was the right

amygdala activated [7].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/temporallobesyndrome-220709151117-1d3c0312/85/temporal-lobe-syndrome-pdf-1-320.jpg)

![84

Neuroanatomy and Neurophysiology

The anatomical confines of the temporal lobes

include (Fig. 5.2):

Lateral

Heschl’s gyrus, planum polare, planum tempo-

rale (BA 41, 42, 22)

Superior temporal middle and inferior temporal

gyrus (BA 22, 21, 20)

Medial

Inferior temporal gyrus (BA 20)

Parahippocampal gyrus (BA 27, 28, 34, 35)

Fusiform gyrus (BA 36)

The posterior temporal lobes are delimited by

an arbitrary line drawn from the parietooccipital

sulcus to the preoccipital notch (indentation in

the inferior temporal gyrus). A horizontal line,

drawn from the midpoint of this particular line to

the lateral sulcus, demarcates the temporal and

parietal lobes [8].

The temporal lobes are intimately tied to all

the other lobes through the association tracts.

Amongst the largest long-range association tracts

include the occipitotemporal and the uncinate

fasciculus. Anterior temporal lobe, inferior fron-

tal lobe lesions, and those of the uncinate fascicu-

lus may be affected together by lesions or disease

states with difficulty in parsing out which is the

most responsible. Accordingly some authors

regard syndromes of the uncinate fasciculus as an

appropriate approach.

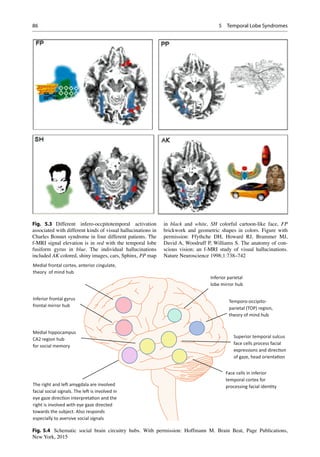

Sensory visual and auditory (much less olfac-

tory) inputs mediate evaluation of a conspecific’s

or other human’s eyes, faces, and body move-

ment. Specialized and separate temporal cortical

areas have been identified for these. Supportive

evidence comes from lesion studies as well as

functional imaging studies with fMRI. The study

by ffytche et al. demonstrated the parts activated

during visual hallucinations for faces, places, and

objects (Fig. 5.3) [9]. These are then subsequently

relayed to superior temporal gyrus and amygdala

for salience evaluation. The mirror neuron cir-

cuitry is concerned with theory of mind detection.

In addition the social semantic memory of the

anterior temporal lobe for faces for example forms

part of the social circuitry (Fig. 5.4).

Fig 5.1 The social

brain hypothesis: group

size for primates and

humans and neocortex

ratio. Index of relative

cortex size (neocortex

ratio) is neocortex

volume divided by the

volume of the rest of the

brain. Figure with

permission: Gamble C,

Gowlett J, Dunbar

R. Thinking Big. How

the evolution of social

life shaped the human

mind. Thames and

Hudson, London 2014

5 Temporal Lobe Syndromes](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/temporallobesyndrome-220709151117-1d3c0312/85/temporal-lobe-syndrome-pdf-2-320.jpg)

![87

Cognitive

Memory: Korsakoff amnestic state

Cortical deafness

Auditory agnosia (inability to identify sounds

despite normal peripheral hearing status)

Auditory paracusias

Auditory hallucinations (simple and complex),

illusions (differentiate from peduncular

hallucinosis)

Disorders of time perception (time may pass with

excessive speed or not at all)

Left

Elementary

Right upper quadrantanopia

Cognitive

Aphasias: Wernicke’s, transcortical sensory, and

anomic

Memory: Verbal amnesia

Visual agnosia

Amusia: Lexical amusia (impairment in reading

music)

Synesthesia

Right

Elementary

Left upper quadrantanopia

Cognitive

Memory: Visuospatial amnesia

Prosopagnosia (occipital–temporal region)

Auditory agnosia—verbal (pure word deafness)

and nonverbal (environmental sounds)

Amusias—receptive and expressive

Delusional misidentification syndromes

Theory of mind impairment (semantic dementia)

[10–17]

Neuropathological Processes

The more commonly encountered pathologies

that involve the temporal lobe in relative isolation

include inferior division middle cerebral artery

territory bland infarction, intracerebral hemor-

rhage (Fig. 5.5), epilepsy, encephalitis, tumors,

and traumatic brain injury. Aside from the apha-

sic presentations that are typical of left temporal

lobe involvement, right temporal lobe syndromes

may be more enigmatic or covert. These include

Kluver–Bucy syndrome (KBS) and Geschwind-

Gastaut syndrome (GGS) presentations or frag-

ments thereof or forme fruste varieties. The KBS,

originally described in monkeys, is rare and gen-

erally ascribed to bilateral lesions although cases

have been reported with unilateral lesions [18].

The presentation includes some or all of the

following:

• Visual agnosia

• Hyperorality

• Placidity

• Altered sexual activity both hypersexuality or

hyposexuality

• Hypermetamorphosis

Human forms of the KBS are being increas-

ingly described with manifestations such as com-

pulsive social kissing reported in a person with

Fig. 5.5 Isolated, discrete, right temporal lobe intracere-

bral hemorrhage (arrow)

Temporal Lobe Elementary Neurological, Cognitive, and Behavioral Presentations and Syndromes](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/temporallobesyndrome-220709151117-1d3c0312/85/temporal-lobe-syndrome-pdf-5-320.jpg)

![88

frontotemporal lobe dementia [19], hypersexual-

ity, and hyperphagia post-right temporal lobec-

tomy for seizure management [20]. KBS may be

permanent or transient and has been reported in

TBI, ICH, FTD, and infectious such as herpes

simplex encephalitis TBI and KBS [21, 22].

Geschwind-Gastaut Syndrome

Although the GGS had for many years been

described in the context of temporal lobe epilepsy,

specifically the interictal phase [23, 24], both iso-

lated bland infarcts and intracerebral hemorrhage

and so the right temporal lobe in particular have

been correlated with this syndrome. The right

temporal lobe had been regarded as one of the so-

called silent areas of the brain but in addition to

the GGS, delusional misidentification syndromes

and a variety of accompanying frontal network

syndromes are frequently encountered with

lesions of this area, if tested for. Importantly these

complex syndromes generally occur without her-

alding sensorimotor deficits (Fig. 5.6) [25].

This syndrome is comprised of three core fea-

tures; the diagnostic process is facilitated by the

Bear-Fedio Inventory (Table 5.1):

1. Viscous personality

2. Metaphysical preoccupation

3. Altered physiological drives.

The viscous personality may be regarded as the

key component of the GG syndrome and may

incorporate one or more of the following features:

• Circumstantiality in discourse

• Overinclusive or excessively detailed narrative

information

• Excessive detail may present with hypergraphia,

painting, drawing

• Undue prolongation of the interpersonal

exchange [26]

Metaphysical Preoccupation

1. Incipient and intense intellectual pursuits per-

taining to morality, religion, and philosophy.

Other behavioral and physiological deviations

such as hyposexuality or hypersexuality, undue

fear, or aggression [23, 24, 27].

Uncinate Fasciculus

The UF is a late-maturing (third–fourth decades),

major brain long-range association fiber tract

connecting the OFC and anterior temporal lobes

(Fig. 5.7). Of note is that it is particularly vulnerable

to traumatic brain shearing-type injury. Its late

maturation makes it a site for neuropsychiatric

Fig.5.6 Isolated right

frontal temporal

encephalomalacia

(arrows) post-

hemorrhage and

craniotomy in person

with classic Geschwind-

Gastaut syndrome

5 Temporal Lobe Syndromes](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/temporallobesyndrome-220709151117-1d3c0312/85/temporal-lobe-syndrome-pdf-6-320.jpg)

![90

syndromes affecting young adults [28]. Three

principal neurophysiological functions of the UF

include episodic memory, social emotional, and

linguistic processing. Pathological states linked

to UF injury include the following:

Social-Emotional Processing

Impairment

The anterior temporal pole is the site for storage

as well as retrieval of socially related memories

and person-related memories and a hub for the

theory of mind circuitry.

Uncinate Fits

These are dreamy states, involving olfactory

and/or gustatory hallucinations, sexual and other

emotional arousals, and involuntary facial or oral

activities [29].

Delusional Misidentification

Syndromes

The UF is the site of injury at times for the delu-

sional misidentification syndromes such as those

with Capgras delusions indicate an impairment in

the face-processing cortical regions to limbic

areas that convey emotional salience or valence

to the faces [30–32].

Cortical Deafness

Due to bilateral lateral temporal lobe lesions

involving Heschl’s gyrus very similar hearing

abnormalities may occur with brainstem stroke due

to anterior inferior cerebellar artery occlusion [33].

Auditory Agnosia

An inability to identify sounds that may be either

verbal (pure word deafness) or nonverbal, despite

normal peripheral hearing status [34].

Auditory Paracusias

These include auditory hallucinations (simple and

complex) and illusions. These need to be differ-

entiated from peduncular hallucinosis due to

pontine infarcts or other lesions that present with

very vivid, colorful, images. These are mostly

visual but can be auditory in nature with reports

of including people talking or shouting, when not

the reality [35–37].

Disorders of Time Perception

The subjective impression that time may pass

with excessive speed or not at all [38, 39].

Amusia

This may include subtypes of receptive, expressive,

and lexical amusia (impairment in reading music [40].

Other Social Disorders Associated

with Temporal Lobe Pathology

(Discussed Under Frontal Network

Syndromes Chapter)

Frontotemporal lobe disorders.

Right—behavioral FTD syndrome

Left—semantic aphasia

Schizophrenia

Autism spectrum conditions

Involuntaryemotionalexpressiondisorder(IEED)

Other Social Disorders Associated

with Temporal Lobe Pathology

(Discussed Under Memory

Syndromes Chapter)

Social impairment associated with memory

impairments

Urbach–Wiethe disease

Autoimmune encephalitis

Acquired prosopagnosia

Progressive prosopagnosia

Prosopagnosia secondary to stroke

The left temporal pole is implicated in the pro-

cessing and storage of proper names, important

for social interaction. This relationship is sup-

ported by both lesion studies and functional

imaging activation reports [41].

5 Temporal Lobe Syndromes](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/temporallobesyndrome-220709151117-1d3c0312/85/temporal-lobe-syndrome-pdf-8-320.jpg)

![91

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI):

Orbitofrontal,Anterior Temporal

Lobe and Uncinate Fasciculus

Predilection of Injury

Although brain injury may be both focal and dif-

fuse, extensive and widespread processes in both

a temporal domain and a spatial domain have

been established. In brief vascular, neurotrans-

mitter perturbation, glucose metabolism, and net-

work disturbances have been established. In

addition there is a more focal frontotemporal pre-

dilection of involvement in TBI. Both blast injury

and nonpenetrating head trauma of the anterior

temporal lobes, the inferior frontal lobes, and the

uncinate fasciculus as a functional unit appear to

bear the brunt of injury. This had been estab-

lished as long ago as 1937 and more recently cor-

roborated by MRI imaging data in 40 patients

[42]. Subsequent functional imaging with PET

scans has also implicated the inferior frontal and

temporal lobes indicating post-acute to chronic

injury hypermetabolism [43]. Finally, resting-

state network imaging has elucidated the much

more diffuse consequences of TBI revealing the

extensive cognitive and neuropsychiatric effects

of the disconnected hub networks [44].

Williams Syndrome

This syndrome presents during childhood with

features of:

Wide mouths

Upturned noses

Small chins

Curious starry eyes

Cardiac abnormalities

Hypercalcemia

Cognitively these children have intellectual

prowess in some areas and weakness in others.

They are described as being hypermusical, hyper-

narrative, and hypersocial. Notably they are

remarkably social displaying effervescence;

readily acquaint strangers are loquacious and

seem to delight in story telling. Some of their

weaknesses are akin to the autism spectrum

people. Certain neuroimaging features have been

reported including relatively smaller occipital

and parietal cortices and larger temporal lobes.

Functional imaging in relation to music has

revealed increased activation in the cerebellum,

temporal lobes, and amygdala [45].

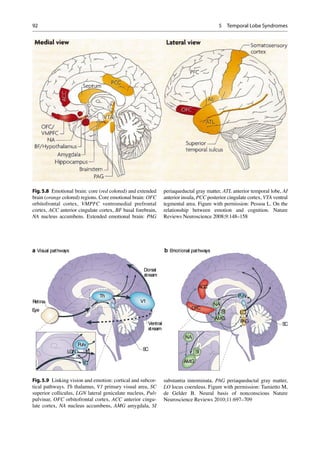

Emotion Disorders

Although the brain’s emotional circuitry is exten-

sive and widespread involving many cortical and

subcortical regions, the temporal lobe serves as

an important hub. Our understanding of the much

more expansive neural circuitry involved has

prompted a reappraisal of the critical, necessary,

and other involved brain regions in emotional

assessment, regulation, and impairments secondary

to disease processes (Fig. 5.8).

Evolutionary Insights

The brain has a two-tier system to help cope with

survival. Primates and humans inherited vision

as the predominant sense which is closely linked

to the emotional brain centers. These enable a

rapid and nonconscious reaction to environmen-

tal stimuli or predators that can be life saving,

being a more ancient and “unconscious,” system

which developed earlier in evolution concerned

with more elementary functions and survival,

not the least of which is dealing with the vast

sensory information that requires processing.

This is a standard infrastructure amongst verte-

brates in general. The conscious component

became a later elaboration of the primate brain

(Fig. 5.9) [46]. The occipitotemporal fasciculus

is a particularly large fiber tract in humans, part

of the inferior longitudinal fasciculus that allows

rapid transfer of visual information to the ante-

rior temporal lobe and amygdaloid complex for

environmental threat or predator evaluation and

human social and emotional salience processing

(Fig. 5.10) [47].

As humans we are particularly cooperative as

a species and our coordinated behavior is in

Emotion Disorders](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/temporallobesyndrome-220709151117-1d3c0312/85/temporal-lobe-syndrome-pdf-9-320.jpg)

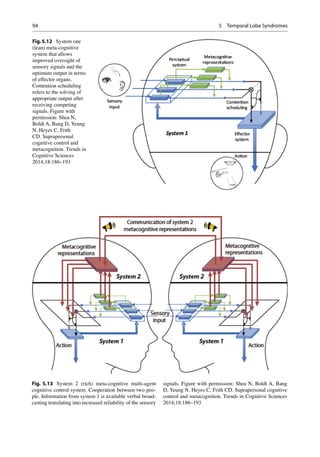

![93

marked contrast to all other animals [48].

Metacognition, a function of the frontopolar

cortex (BA 10), represents the apex of higher

cortical function ability. This region may be

divided into medial lateral and anterior regions

within BA 10, mediating self-reflection, intro-

spection, the monitoring and processing of

internal states with the externally acquired infor-

mation, episodic memory subfunctions such as

source memory and prospective memory, and

contextual and retrieval verification (Fig. 5.11)

[49, 50].

Shea et al. have proposed a two-level meta-

cognitive control system, a system 1 and system

2. System 1 (also called cognitively lean system)

of metacognition operates nonconsciously or

implicitly and is hypothesized to be involved in

processing information from the senses for intra-

personal cognition relevant to many animals

(Fig. 5.12). System 2 (also termed cognitively

rich system) is thought to be unique to humans

and is concerned with processing high-level

information amongst several conspecifics or peo-

ple, also termed suprapersonal control (Fig. 5.13).

Shea et al. conjecture that the suprapersonal

coordination metacognitive system antedated

system 1 or that which controlled the intraper-

sonal cognitive processes that underlie emotional

intelligence and inhibitory control [51]. In line

with these hypotheses is that one of the core frontal

functions of disinhibition was a critical development

in human evolution.

Fig.5.10 Occipito-

temporal pathway.

Figure with permission:

Catani M. Jones DK,

Donato R, ffytche

DH. Occipito-temporal

connections in the

human brain. Brain

2003;126:2093–2107

MNT

MLT

EP

EP

Fig. 5.11 Frontopolar cortex subregion activation pat-

terns (regional cerebral blood flow and blood oxygen level

dependent). MLT multitasking, MNT mentalizing, EP epi-

sodic memory. Figure adapted from: Gilbert SJ, Spengler

S, Simons JS, Steele JD, Lawrie SM, Frith CD, Burgess

PW. Functional Specialization within the Rostral

Prefrontal Cortex (Area 10): A Meta-analysis. Journal of

Cognitive Neuroscience 2006;18:932–948

Emotion Disorders](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/temporallobesyndrome-220709151117-1d3c0312/85/temporal-lobe-syndrome-pdf-11-320.jpg)

![95

Clinical

Emotional intelligence (EI) defined differently

according to the various clinical brain specialties

such as psychology, neurology, and psychiatry. EI

has been shown to be important for personal suc-

cess and career success and in navigating the social

complexities in day-to-day living [52]. EI impair-

ment may be apparent in both apparently healthy

people and after brain illnesses such as stroke, fron-

totemporal lobe dementia, Alzheimer’s disease,

and multiple sclerosis [53, 54]. Baron for example

has proposed that EI comprises of the group of

abilities that allow one to

1. Understand one’s own emotions and be able

to express feelings

2. Understand how others that one interacts with

feel and how one relates to them

3. Manage and be in control of one’s own

emotions

4. Use one’s emotions in adapting to one’s

environment

5. Generate positive emotions and use them for

self-motivation in facing challenges

The neural circuitry for EI involves orbitofron-

tal, anterior cingulate, the insula, and amygdaloid

complex regions [55, 56]. Processes that injure

these areas in particular include traumatic brain

injury, stroke, multiple sclerosis, and frontotempo-

ral lobe disorders. A holistic clinical brain injury

assessment should therefore involve all the clinical

brain specialties, neurological, neuropsychiatric,

psychological, and speech and language. EI assess-

ment has already been extensively embraced in the

corporate arena in view of its relationship with not

only career success but also productivity and insti-

tutional health [57, 58] and EI is amenable for

behavioral intervention programs [59, 60]. In a

study involving stroke patients, many different

brain lesions affected EI scores, including with

frontal, temporal, subcortical, and subtentorial

stroke lesions. The most significant abnormalities

were however associated with the frontal and tem-

poral region lesions, supporting Pessoa’s extended

emotional brain circuitry [61, 62].

Involuntary Emotional Expression

Disorder

Involuntary emotional expression disorder

(IEED) refers to clinically recognized syn-

dromes that are characterized by intermittent

inappropriate laughing and/or crying as well as

intermittent emotional lability. Lesion studies

have implicated the frontal primary motor (BA

4), premotor (BA 6), supplementary motor (BA

8), dorsal anterior cingulate gyrus, posterior

insular and parietal regions, and corticopontine

projections to the amygdala, hypothalamus,

and periaqueductal gray matter. In addition sei-

zure activity of these circuits may result in

laughing (gelastic) or crying episodes (dys-

crastic) [63]. Dextromethorphan is a sigma-1

receptor agonist and noncompetitive N-methyl-

d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist.

Quinidine is a competitive inhibitor of CYP2D6

which increases plasma levels of dextrometho-

rphan. In placebo, double-blinded studies

using validated IEED scales, the Center for

Neurologic Study-Lability Scale, in multiple

sclerosis and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

patients, the combination drug was superior to

placebo [64].

References

1. Schumann C, Amaral DG. Stereological estimation

of the number of neurons in the human amygdaloid

complex. J Comp Neurol. 2005;491:320–9.

2. Bastir M, Rosas A, Gunz P, Peña-Melian A, Manzi G,

Harvati K, et al. Evolution of the base of the brain in

highly encephalized human species. Nat Commun.

2011;2:588. doi:10.1038/ncomms1593.

3. Semendeferi K, Barger N, Schenker N. Brain reorgani-

zation in humans and apes. The human brain evolving.

Gosport, IN: Stone Age Institute Press; 2010.

4. Barton RA, Aggleton JP, Grenyer R. Evolutionary

coherence of the mammalian amygdala. Proc Biol

Sci. 2003;270:539–43.

5. Dunbar RIM. The social brain: mind, language and

society in evolutionary perspective. Ann Rev

Anthropol. 2003;32:163–81.

6. Pelphrey KA, Viola RJ, McCarthy G. When strang-

ers pass: processing of mutual and averted social

gaze in the superior temporal sulcus. Psychol Sci.

2004;15:598–603.

References](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/temporallobesyndrome-220709151117-1d3c0312/85/temporal-lobe-syndrome-pdf-13-320.jpg)