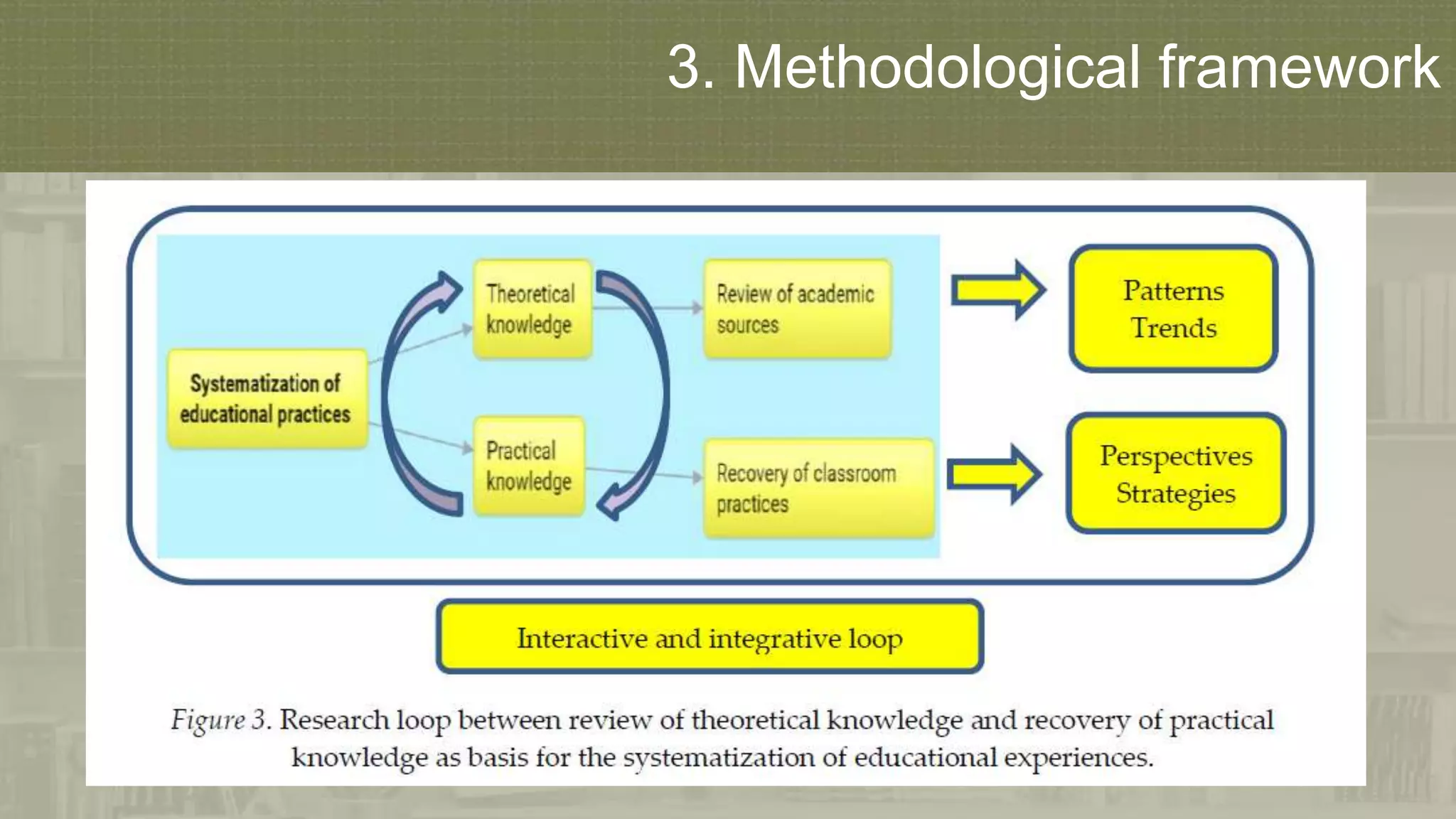

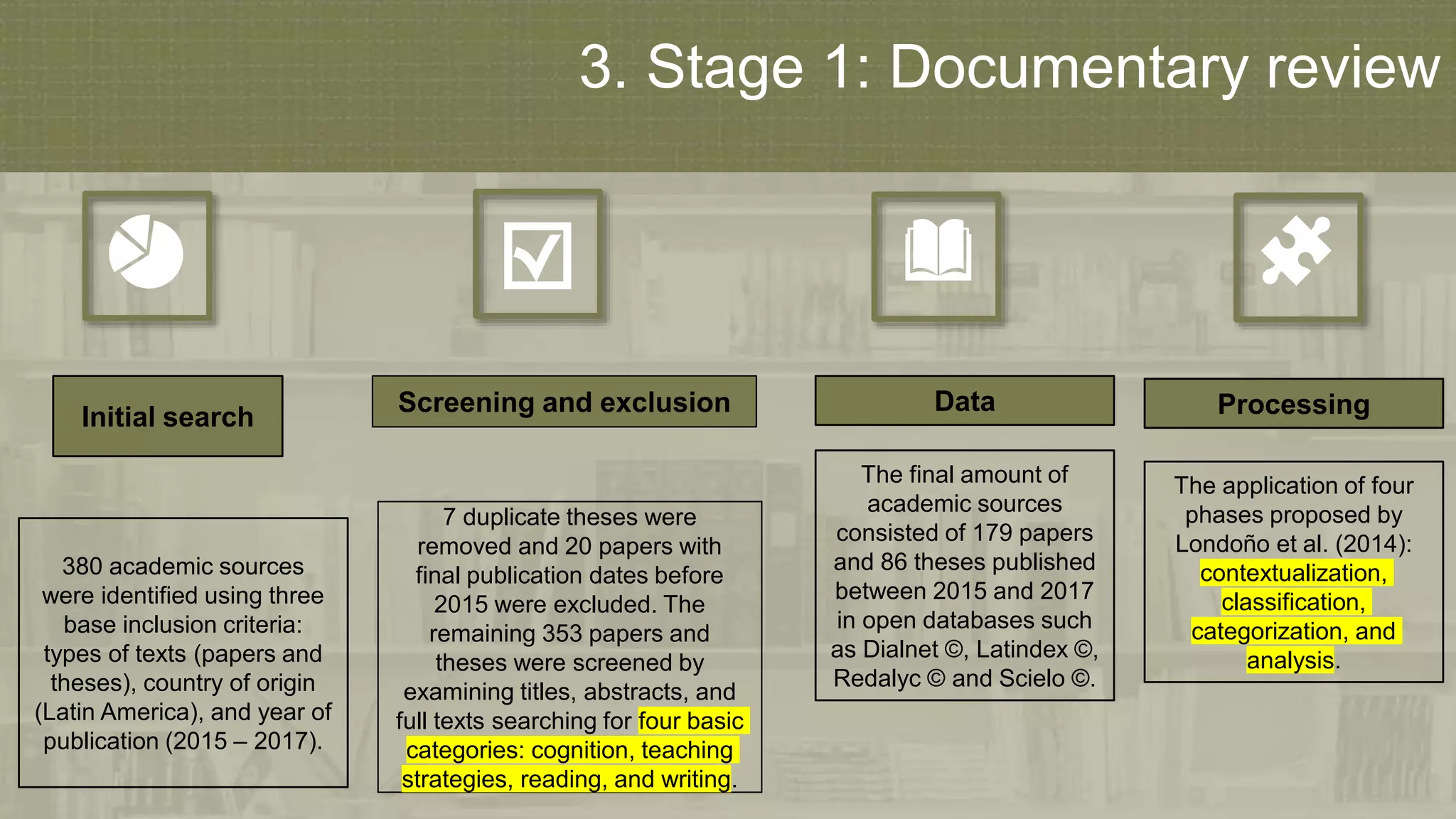

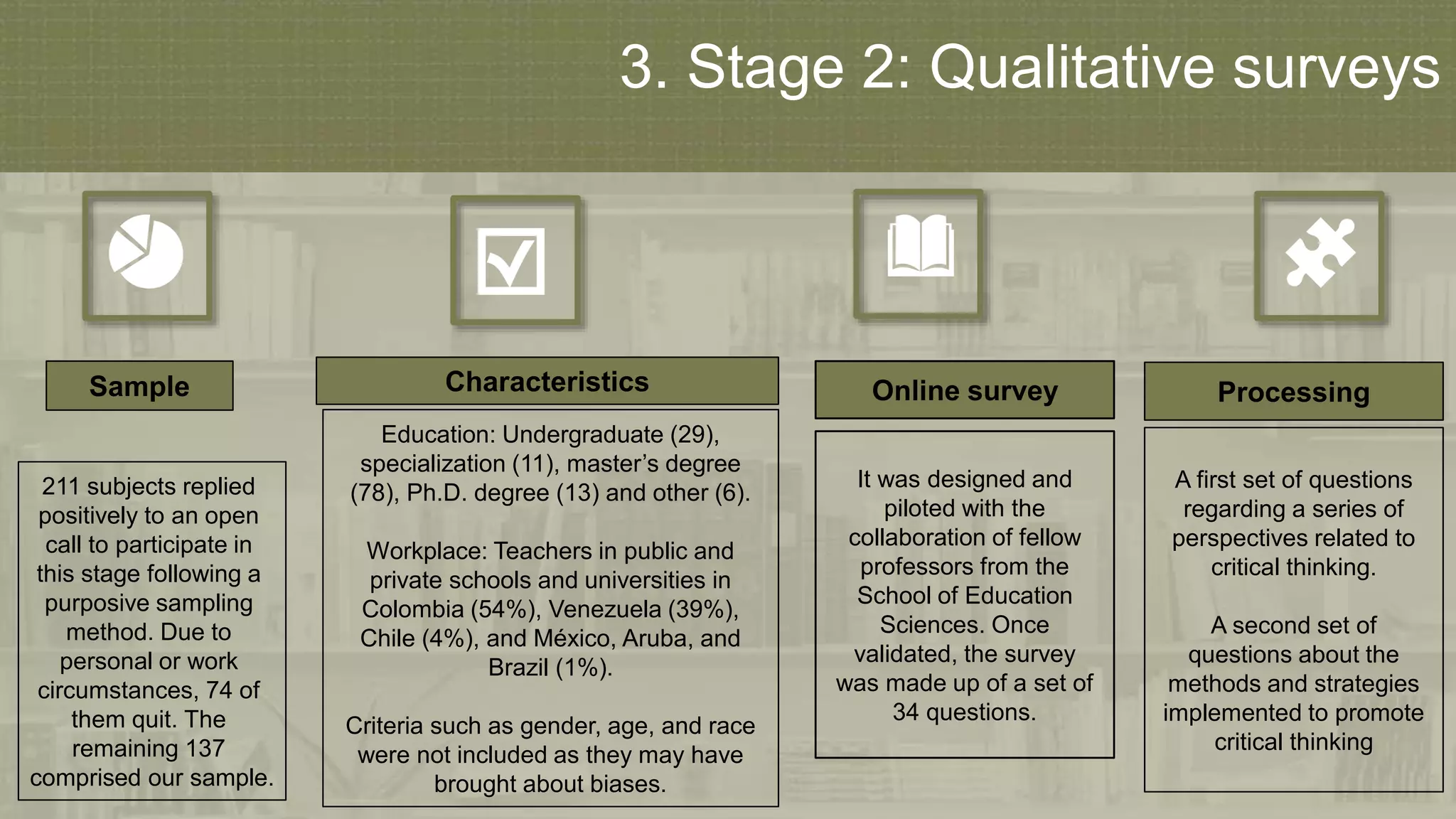

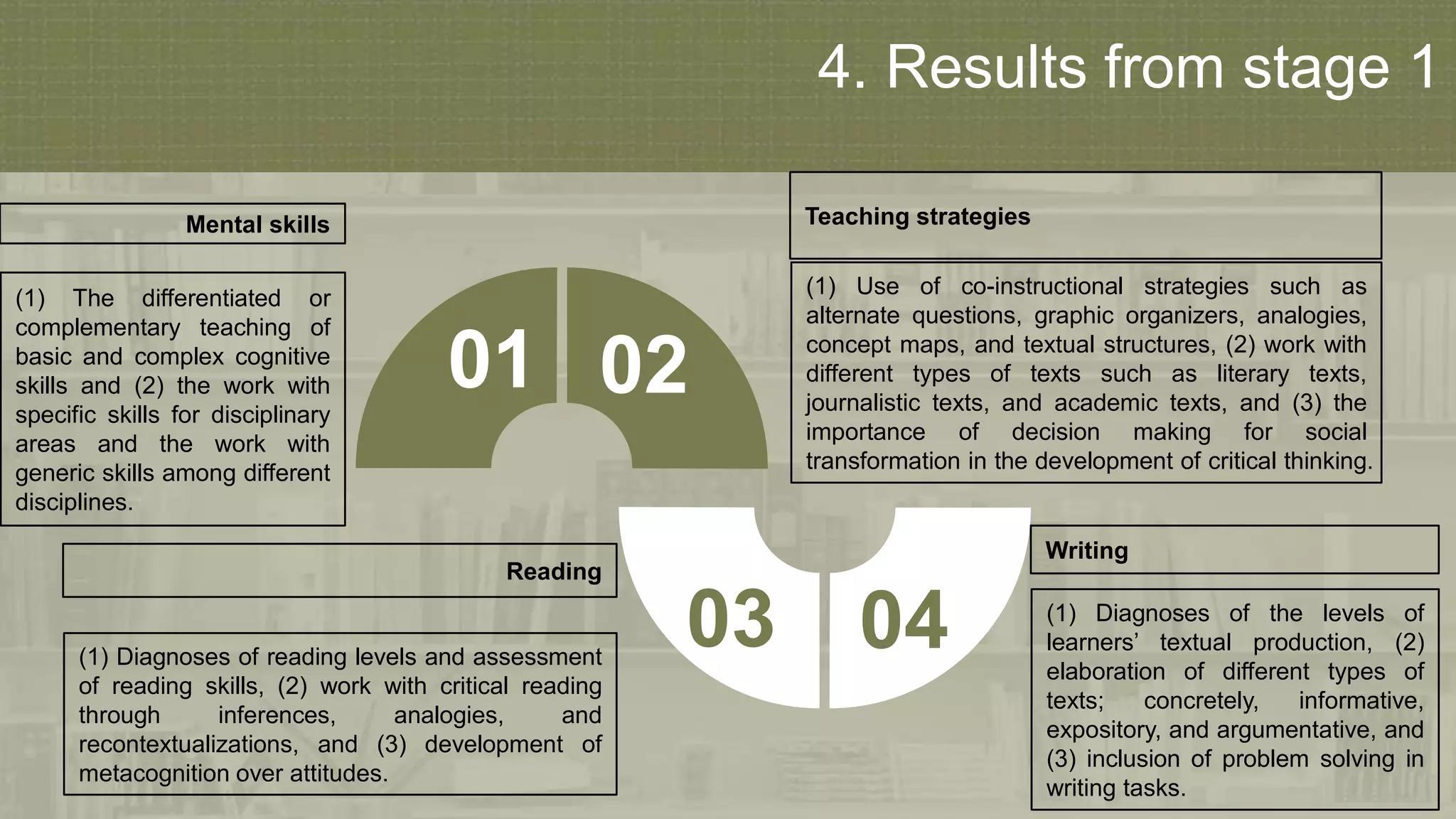

This document summarizes the findings of a research project on teacher education and critical thinking in EFL teaching. The research had two stages: a documentary review of 179 academic sources, and qualitative surveys with 137 EFL teachers. Key findings from the documentary review included the importance of developing cognitive skills, critical reading strategies, using various teaching strategies, and promoting different types of writing. Survey results showed teachers viewed critical thinking as developing higher-order thinking skills and saw value in learner-centered activities. The conclusion is that EFL teacher education programs should adopt progressive pedagogies to help teachers develop knowledge, skills, and attitudes to be lifelong learners and agents of social change.