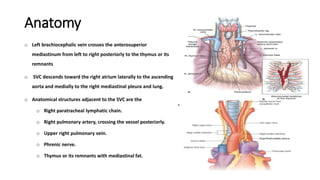

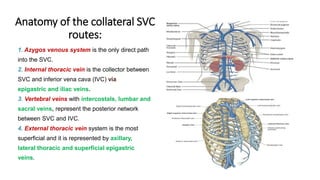

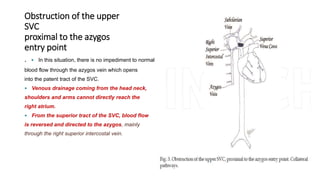

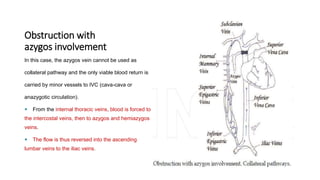

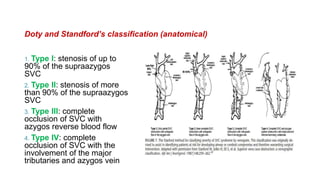

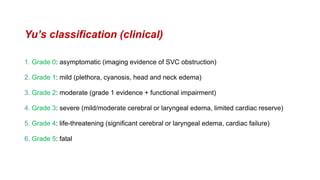

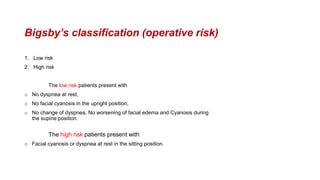

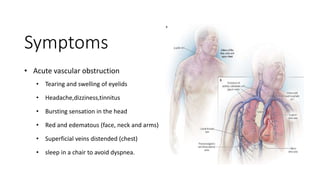

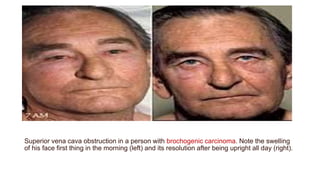

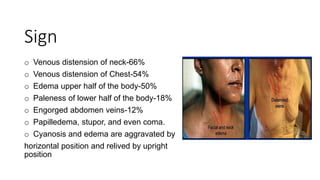

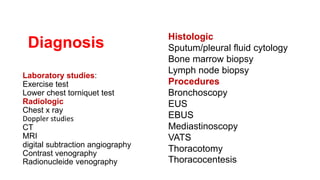

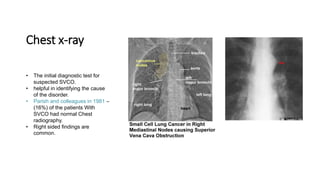

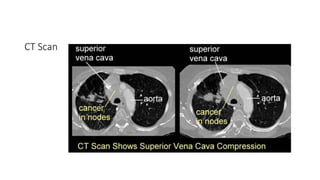

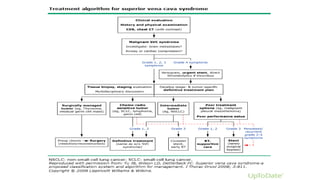

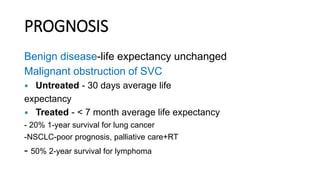

Superior vena cava obstruction (SVCO) results from compression or obstruction of the superior vena cava (SVC) system, commonly due to malignancy, particularly lung cancer. The document reviews the anatomy, etiology, history, symptoms, diagnostic methods, and treatment options, noting that the incidence of SVCO has increased due to factors like catheter use. Treatment focuses on symptom relief and may include medical care, radiation, chemotherapy, thrombolytic therapy, stents, and surgery, with varying prognoses based on whether the obstruction is benign or malignant.