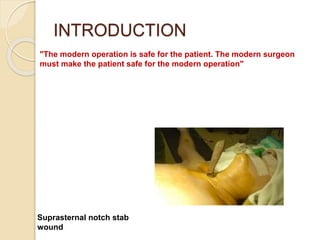

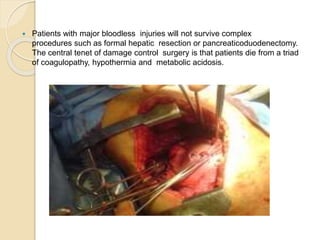

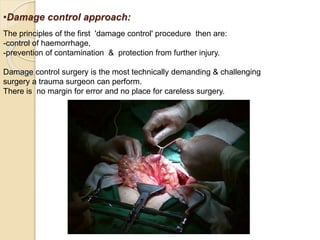

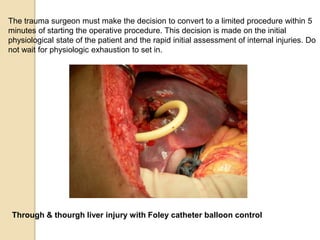

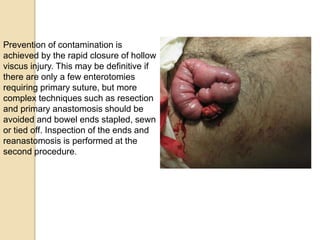

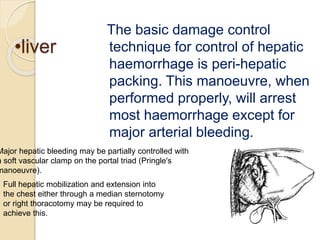

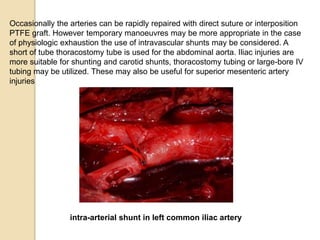

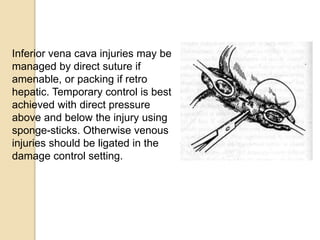

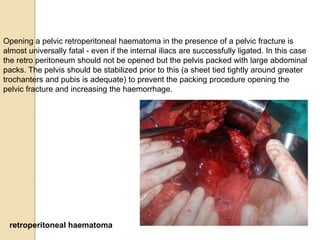

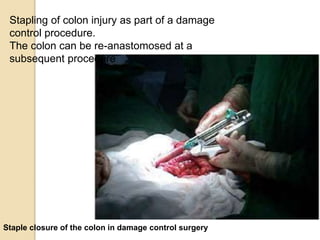

Damage control surgery is a vital technique for trauma patients, focusing on controlling hemorrhage and stabilizing metabolic derangements before performing definitive procedures. Key principles include rapid hemorrhage control, contamination prevention, and minimizing physiological exhaustion from hypothermia, acidosis, and coagulopathy. The process involves immediate surgical intervention with delayed comprehensive repair to improve patient survival rates amidst life-threatening injuries.