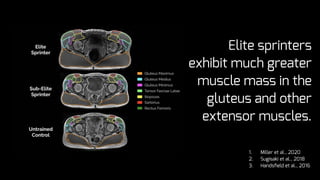

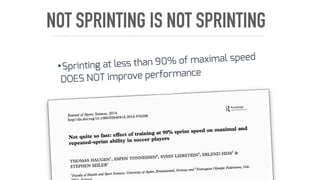

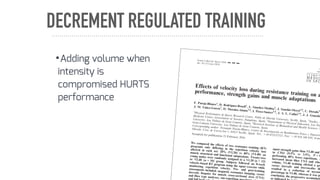

The document discusses determinants of speed and principles of elite speed development. It covers muscular, mechanical, kinetic, and neuromuscular factors that influence speed. Some key points include:

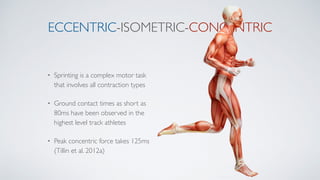

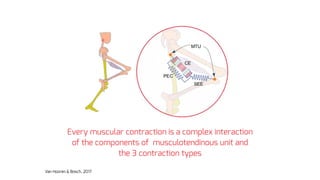

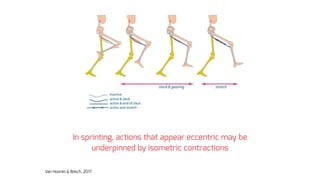

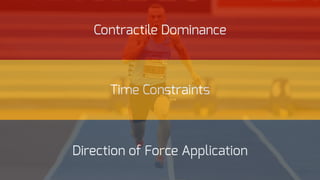

- Sprinting requires complex interactions between eccentric, isometric, and concentric muscle contractions under extreme time constraints.

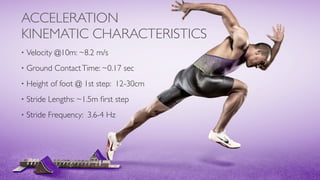

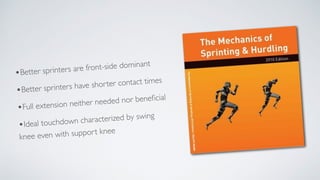

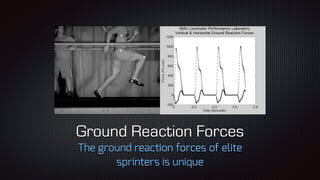

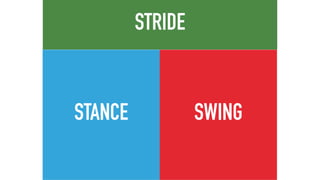

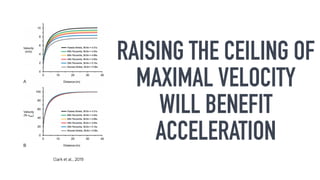

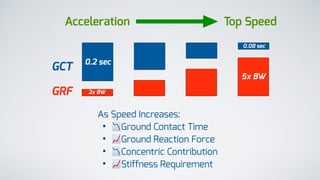

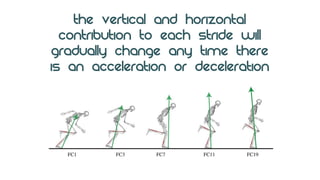

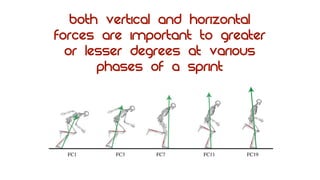

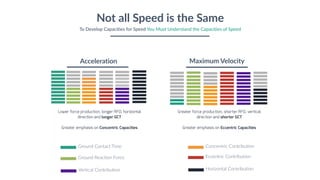

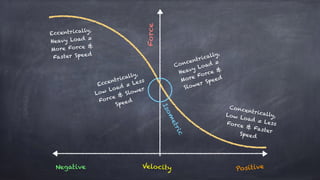

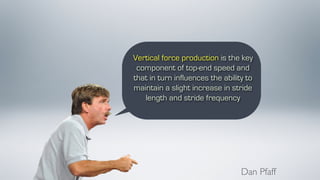

- Mechanical factors like ground contact time, stride length and frequency differentiate acceleration from maximum velocity.

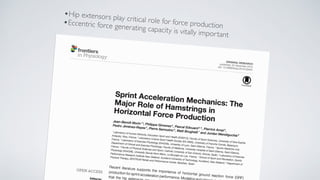

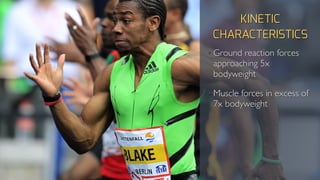

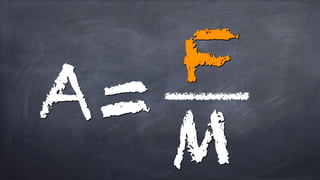

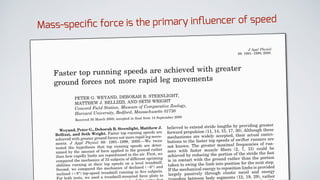

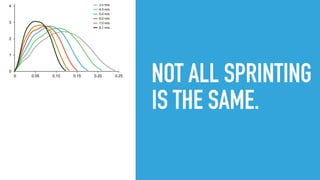

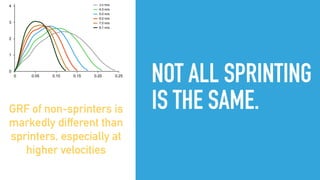

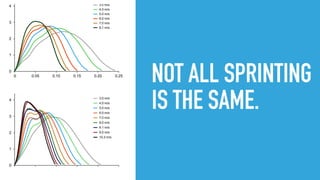

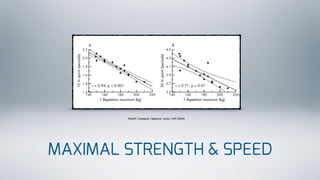

- Faster sprinters apply more mass-specific force to the ground in a shorter period of time.

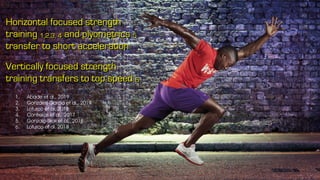

- Training should target the force-velocity continuum from maximum strength to maximum speed. Both horizontal and vertical strength are important for acceleration and top speed respectively.

![[Muscular Factors]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2021belgiumathleticssciencepracticeofelitespeeddevelopment-210703224927/85/Science-Practice-of-Elite-Speed-Development-3-320.jpg)

![[Mechanical Factors]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2021belgiumathleticssciencepracticeofelitespeeddevelopment-210703224927/85/Science-Practice-of-Elite-Speed-Development-10-320.jpg)

![[Kinetic Factors]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2021belgiumathleticssciencepracticeofelitespeeddevelopment-210703224927/85/Science-Practice-of-Elite-Speed-Development-24-320.jpg)

![[Acceleration:Max Velocity]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2021belgiumathleticssciencepracticeofelitespeeddevelopment-210703224927/85/Science-Practice-of-Elite-Speed-Development-51-320.jpg)

![[Neuromuscular]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2021belgiumathleticssciencepracticeofelitespeeddevelopment-210703224927/85/Science-Practice-of-Elite-Speed-Development-63-320.jpg)

![[Mechanical]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2021belgiumathleticssciencepracticeofelitespeeddevelopment-210703224927/85/Science-Practice-of-Elite-Speed-Development-70-320.jpg)

![With regards to what is

relevant to the coach &

athlete, horizontal & vertical

forces are quite similar [1/2]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2021belgiumathleticssciencepracticeofelitespeeddevelopment-210703224927/85/Science-Practice-of-Elite-Speed-Development-74-320.jpg)

![Horizontal force is just

vertical force turned on

its side [2/2]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2021belgiumathleticssciencepracticeofelitespeeddevelopment-210703224927/85/Science-Practice-of-Elite-Speed-Development-75-320.jpg)

![Horizontal force is just

vertical force turned on

its side [2/2]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2021belgiumathleticssciencepracticeofelitespeeddevelopment-210703224927/85/Science-Practice-of-Elite-Speed-Development-76-320.jpg)

![[General Speed Training

Guidelines]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2021belgiumathleticssciencepracticeofelitespeeddevelopment-210703224927/85/Science-Practice-of-Elite-Speed-Development-98-320.jpg)

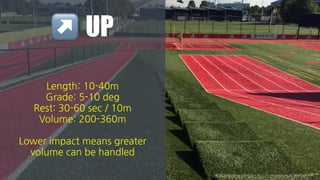

![[Hill Sprinting]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2021belgiumathleticssciencepracticeofelitespeeddevelopment-210703224927/85/Science-Practice-of-Elite-Speed-Development-106-320.jpg)

![[Resisted Sprinting]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2021belgiumathleticssciencepracticeofelitespeeddevelopment-210703224927/85/Science-Practice-of-Elite-Speed-Development-109-320.jpg)

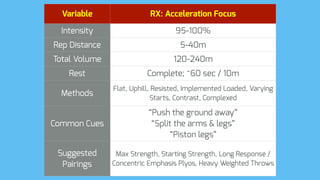

![[Acceleration

Development]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2021belgiumathleticssciencepracticeofelitespeeddevelopment-210703224927/85/Science-Practice-of-Elite-Speed-Development-111-320.jpg)

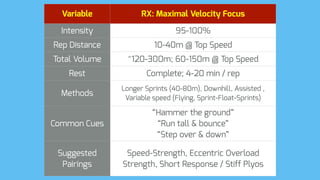

![[Top Speed Development]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2021belgiumathleticssciencepracticeofelitespeeddevelopment-210703224927/85/Science-Practice-of-Elite-Speed-Development-113-320.jpg)