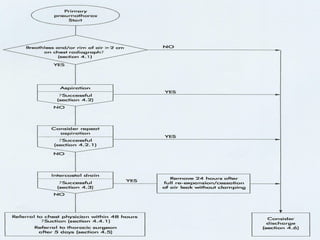

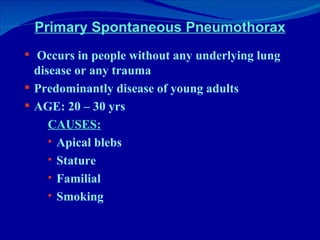

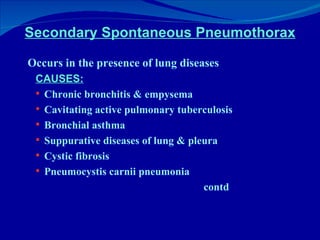

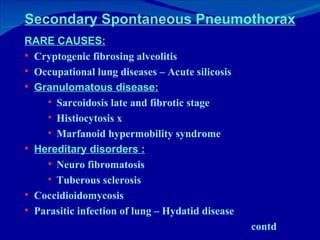

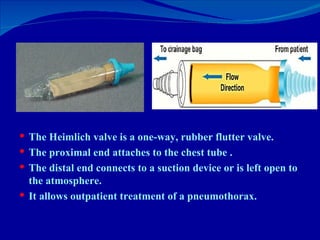

This document discusses the diagnosis and treatment of primary and secondary spontaneous pneumothorax. Primary pneumothorax typically occurs in young, healthy individuals and is usually treated initially with observation or simple aspiration. Secondary pneumothorax occurs in the context of underlying lung disease and may require chest tube drainage. Treatment depends on factors such as pneumothorax size and severity of symptoms. Surgical intervention is recommended for recurrent or persistent cases.

![Complications of ICD Penetration of the major organs such as lung, stomach, spleen, liver, heart and great vessels, and are potentially fatal. Pleural infection [ Empyema ] Surgical emphysema [ Malpositioned, kinked, blocked or clamped tube , small tube with large leak ]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/spontaneous-pneumothorax-an-update-1233086237554357-1/85/Spontaneous-Pneumothorax-An-Update-32-320.jpg)