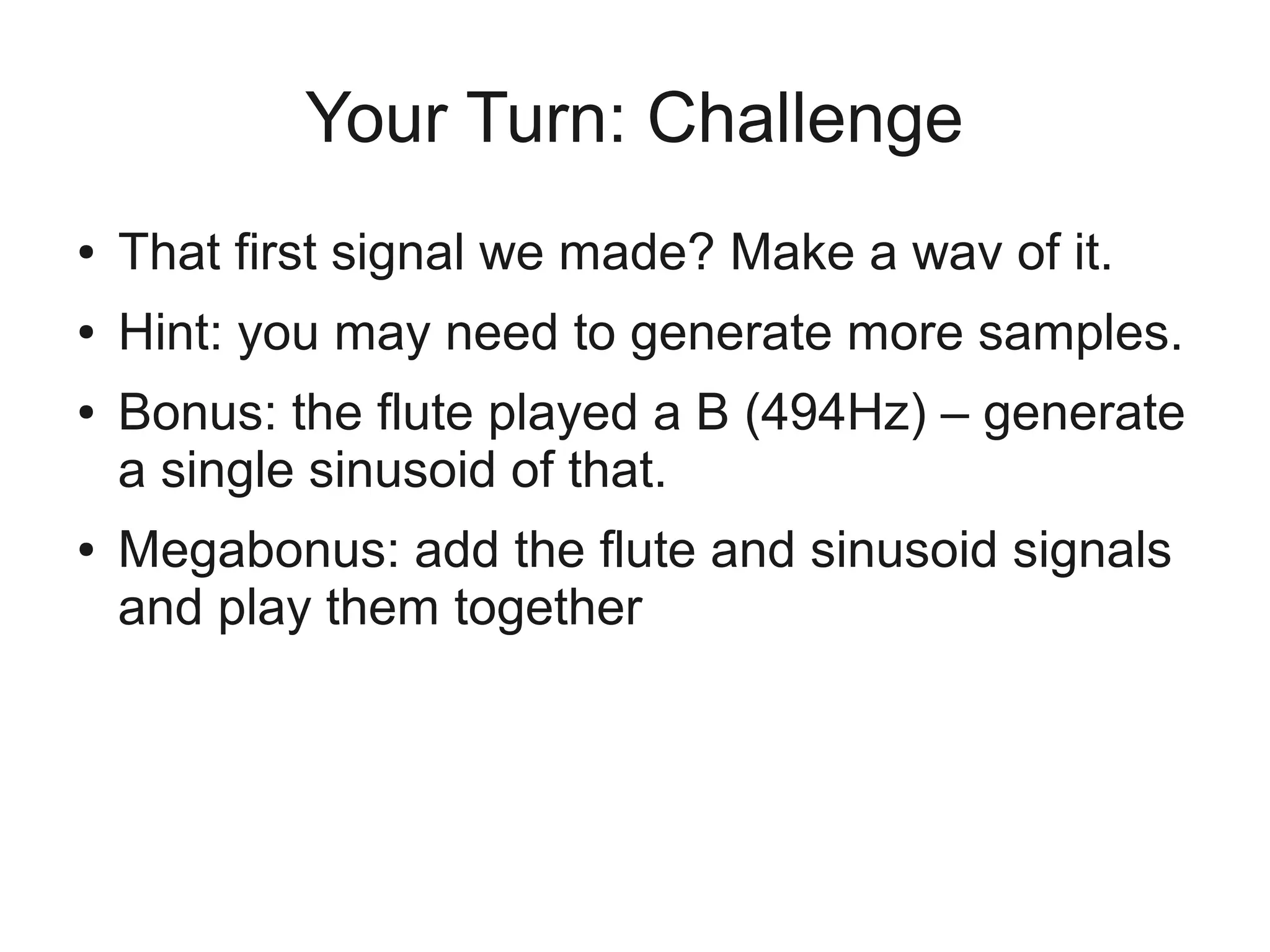

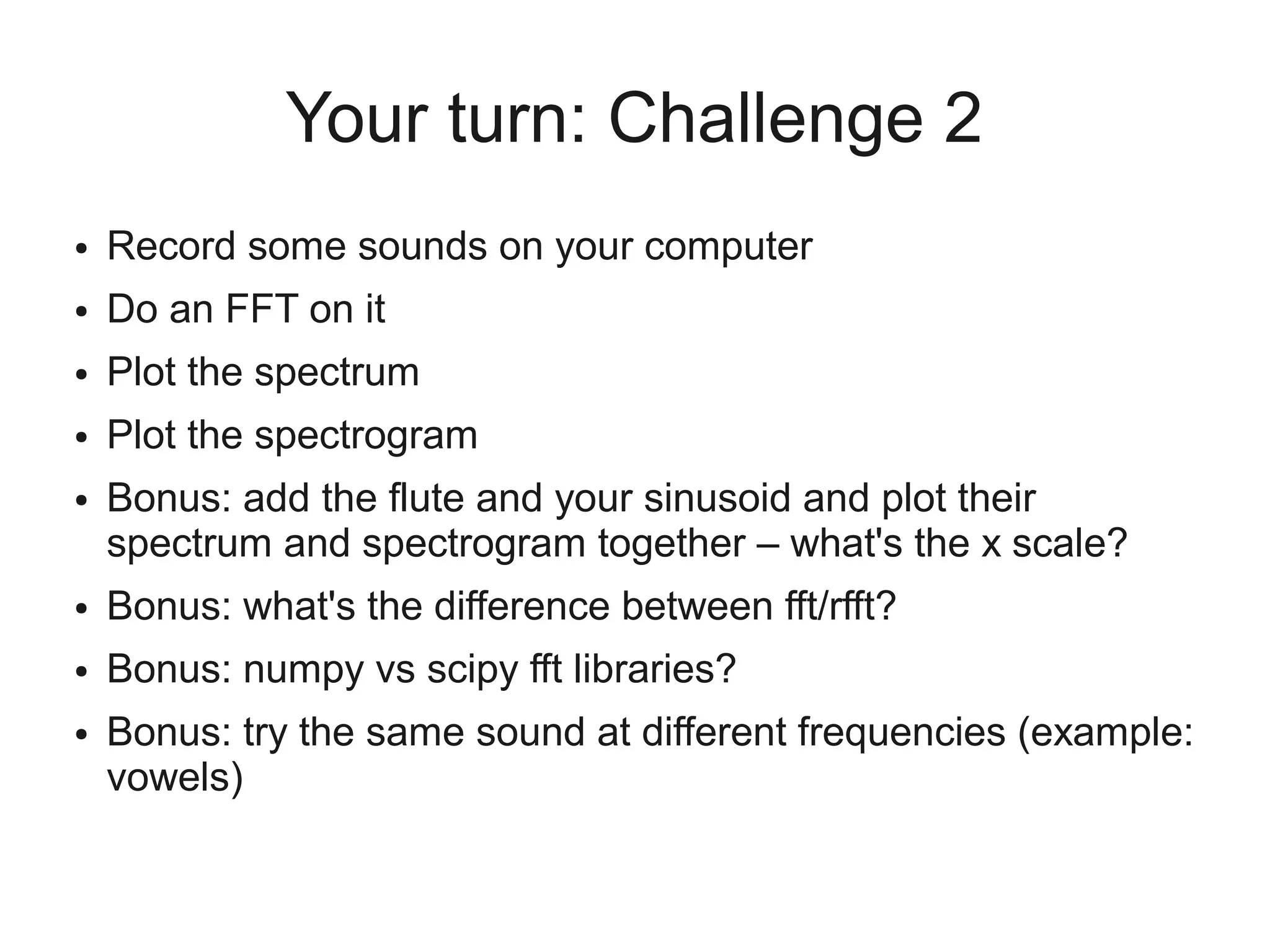

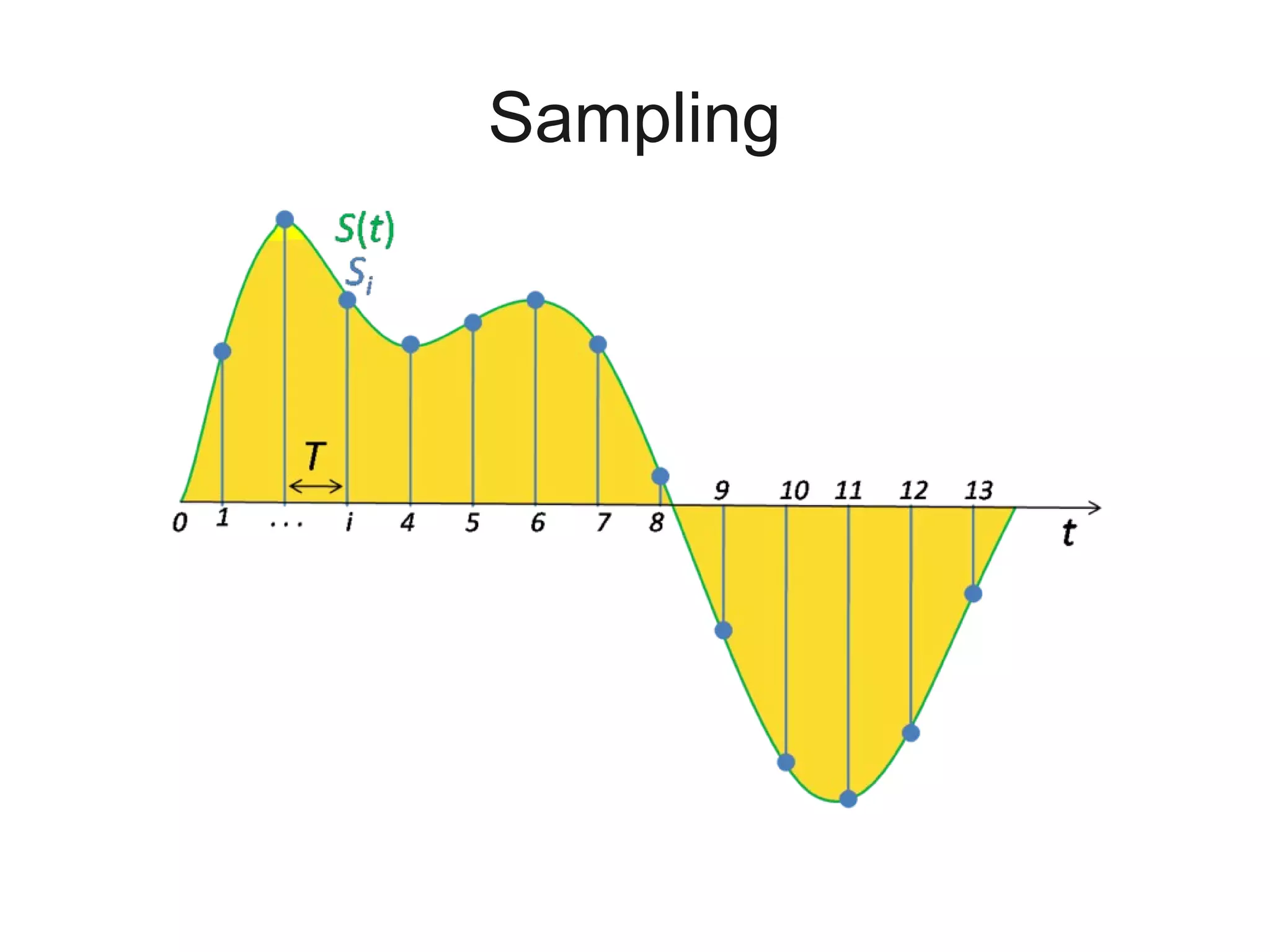

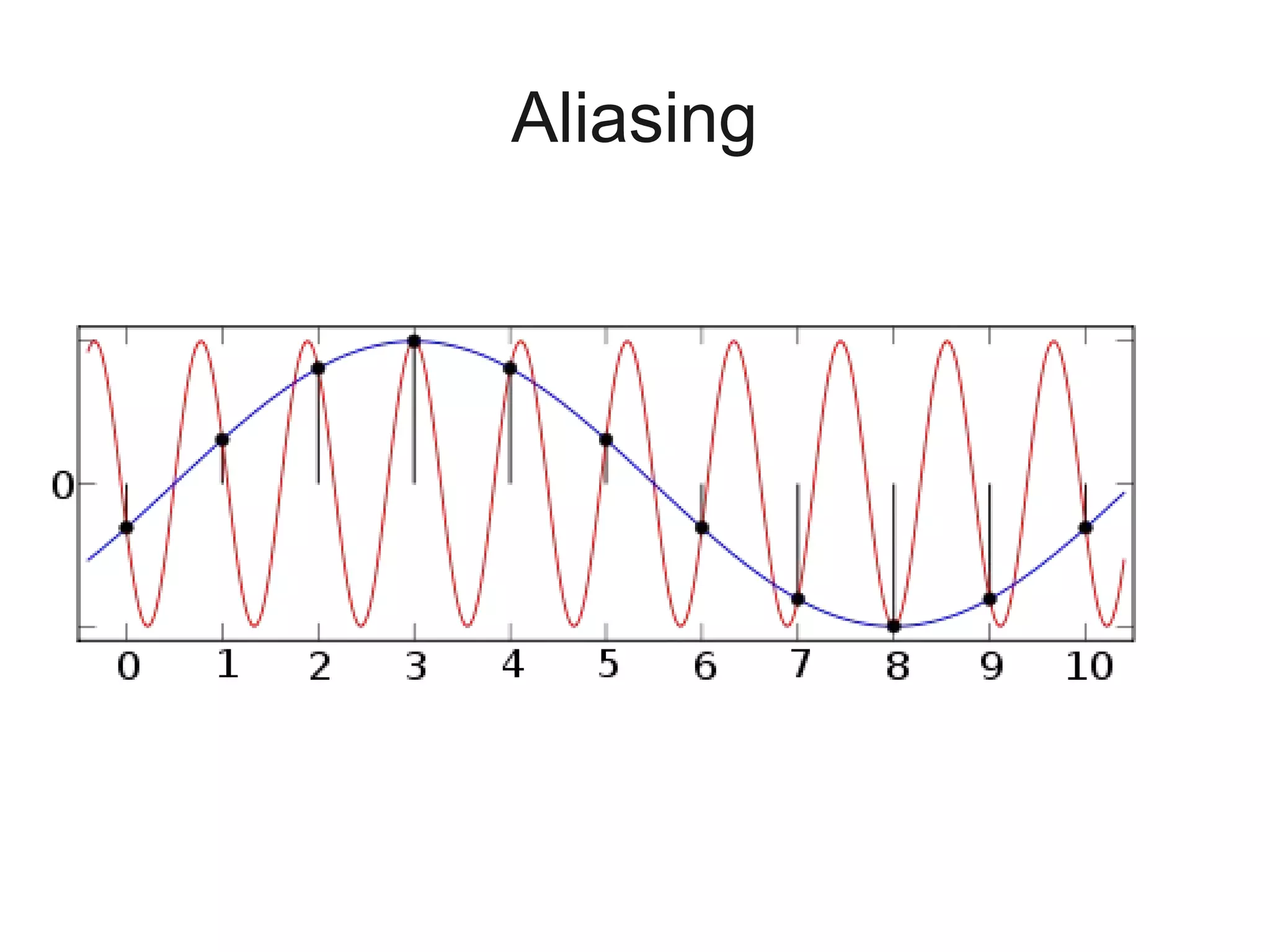

This document is a tutorial on digital signal processing using Python, focusing on audio analysis and manipulation. It covers concepts like Fourier transforms, signal visualization, sampling, and filtering, while providing hands-on coding exercises that encourage interactive learning. The tutorial is designed for participants with basic knowledge of Python and aims to accomplish in three hours what typically takes 144 hours in a standard class.

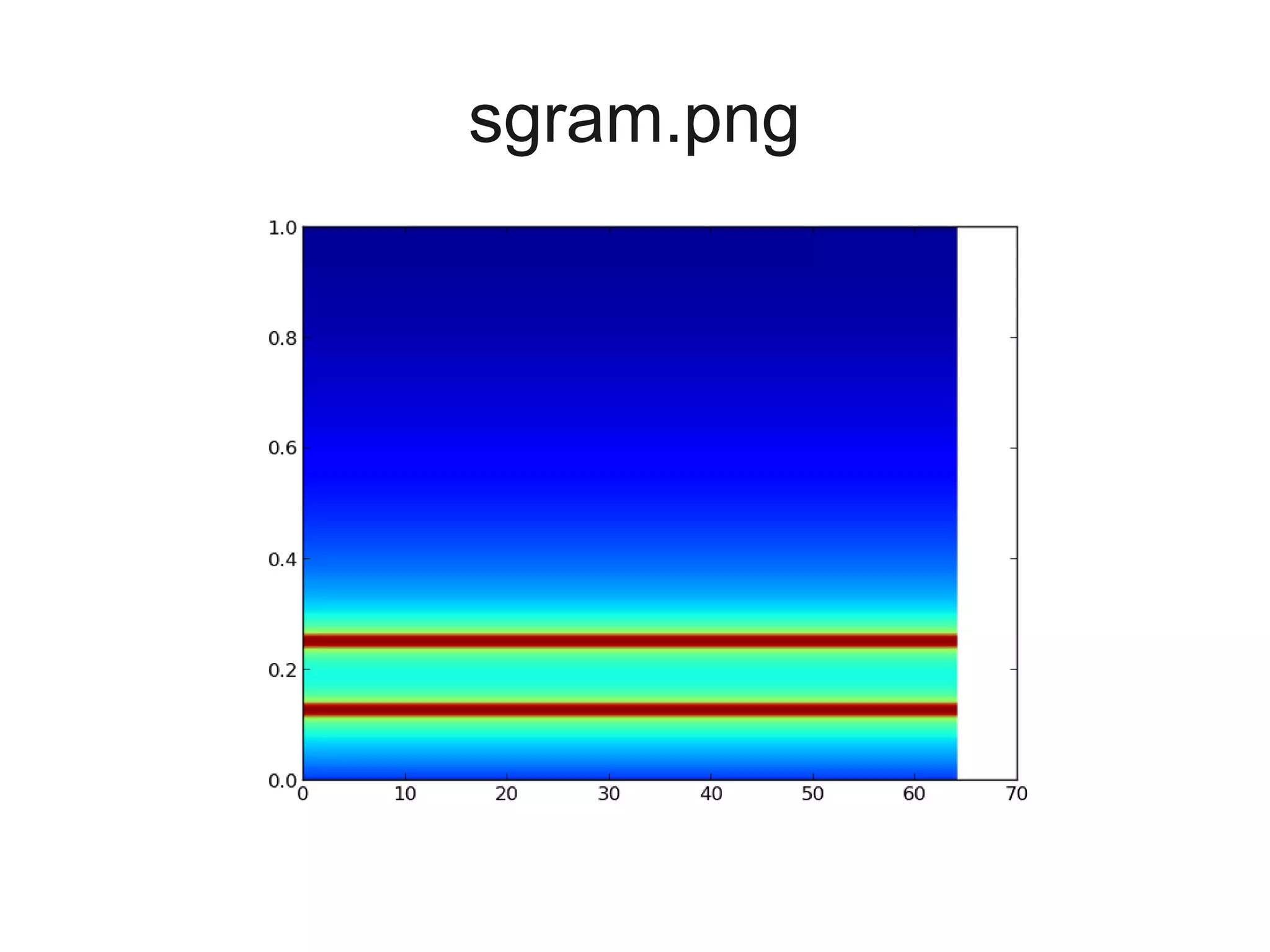

![Let's define a function to get the

data from the .wav file, and use it.

def getwavdata(file):

return scipy.io.wavfile.read(file)[1]

audio = getwavdata('flute.wav')

# more detail on scipy.io.wavfile.read

# in sigproc-outline.py, lines 117-123](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sigproc-selfstudy-130318120948-phpapp01/75/Digital-signal-processing-through-speech-hearing-and-Python-31-2048.jpg)

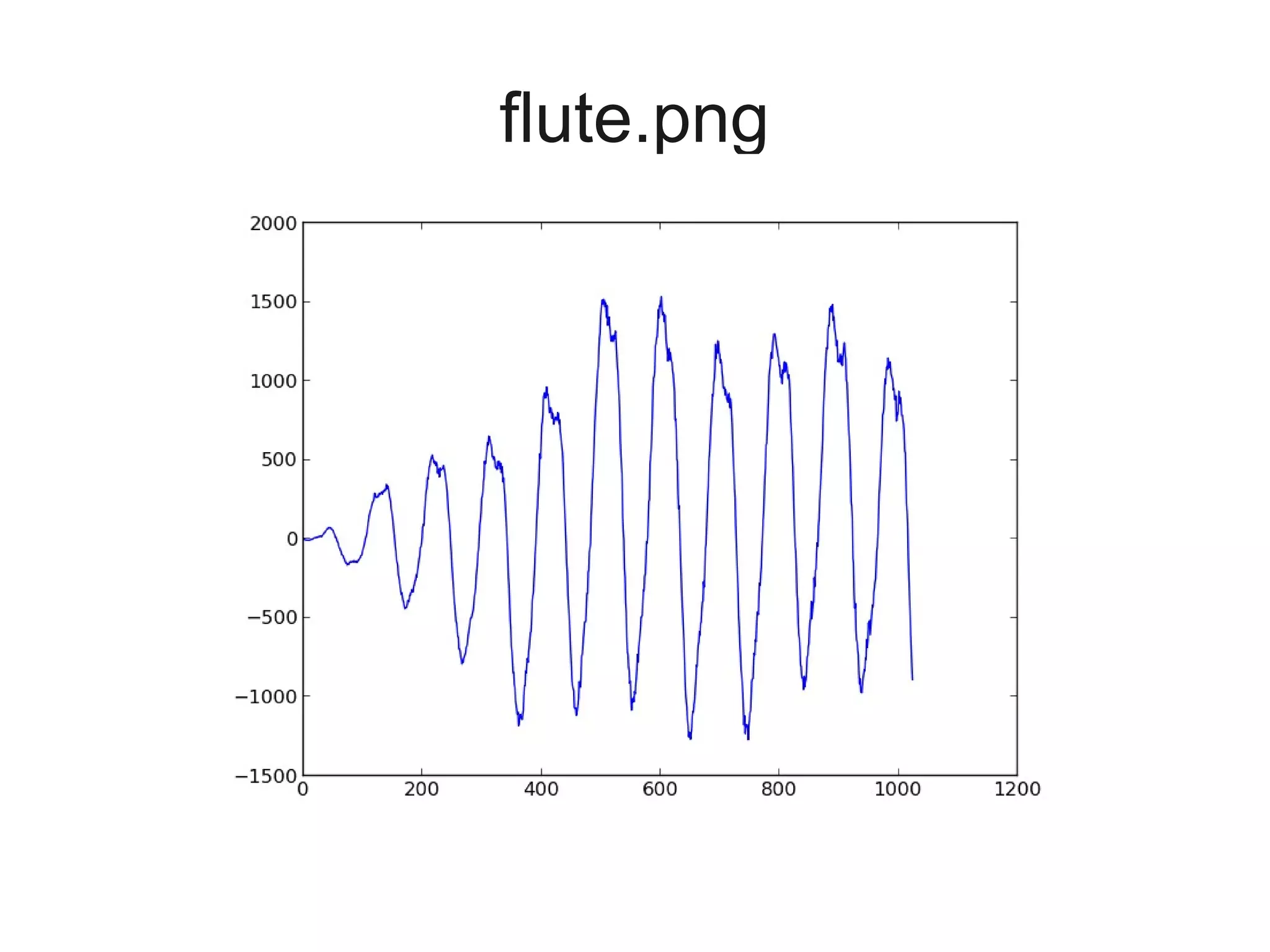

![Now let's see what this looks like in

the time domain. We've got a lot of

data points, so we'll only plot the

beginning of the signal here.

makegraph(audio[0:1024], 'flute.png')](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sigproc-selfstudy-130318120948-phpapp01/75/Digital-signal-processing-through-speech-hearing-and-Python-33-2048.jpg)

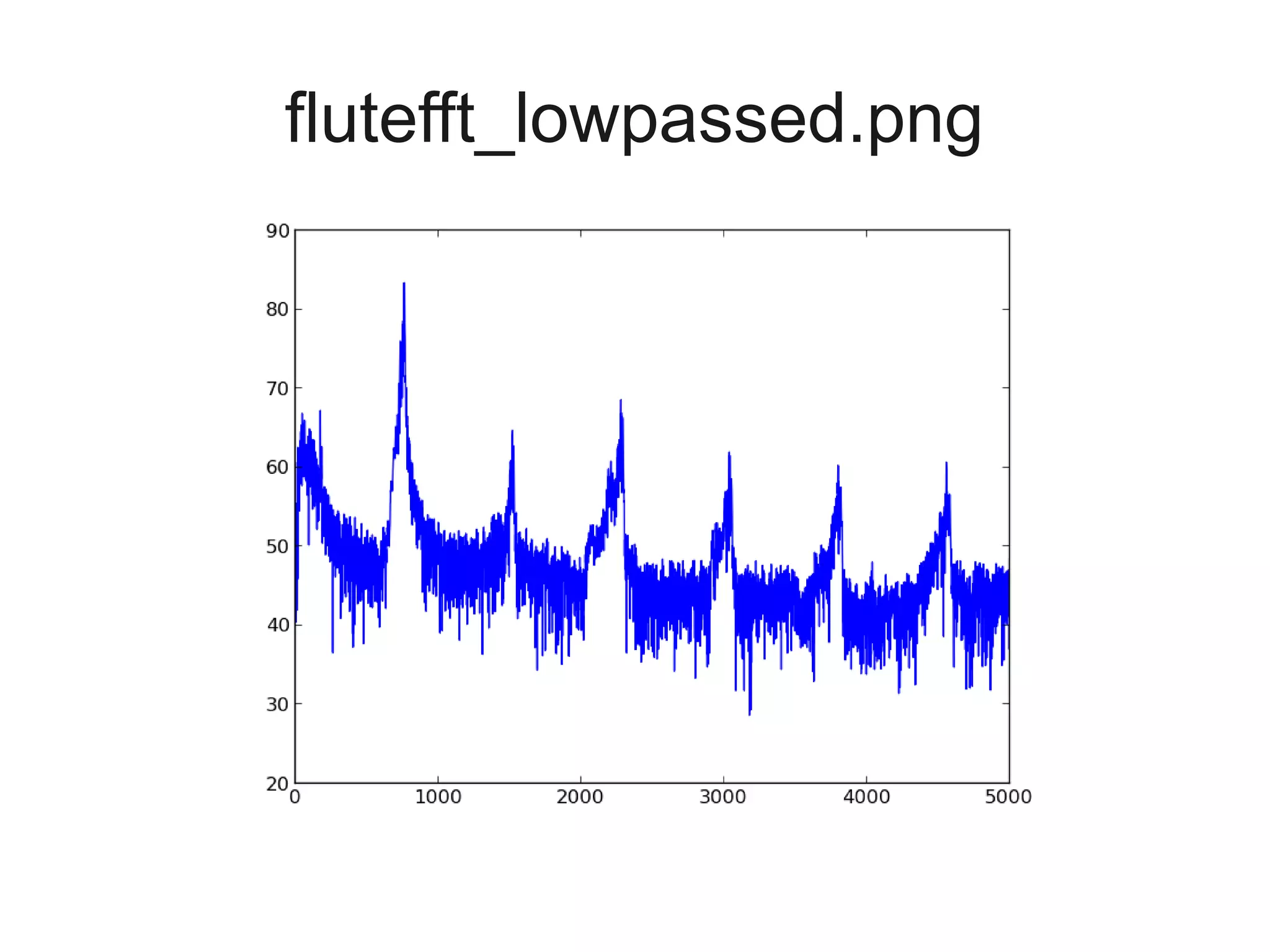

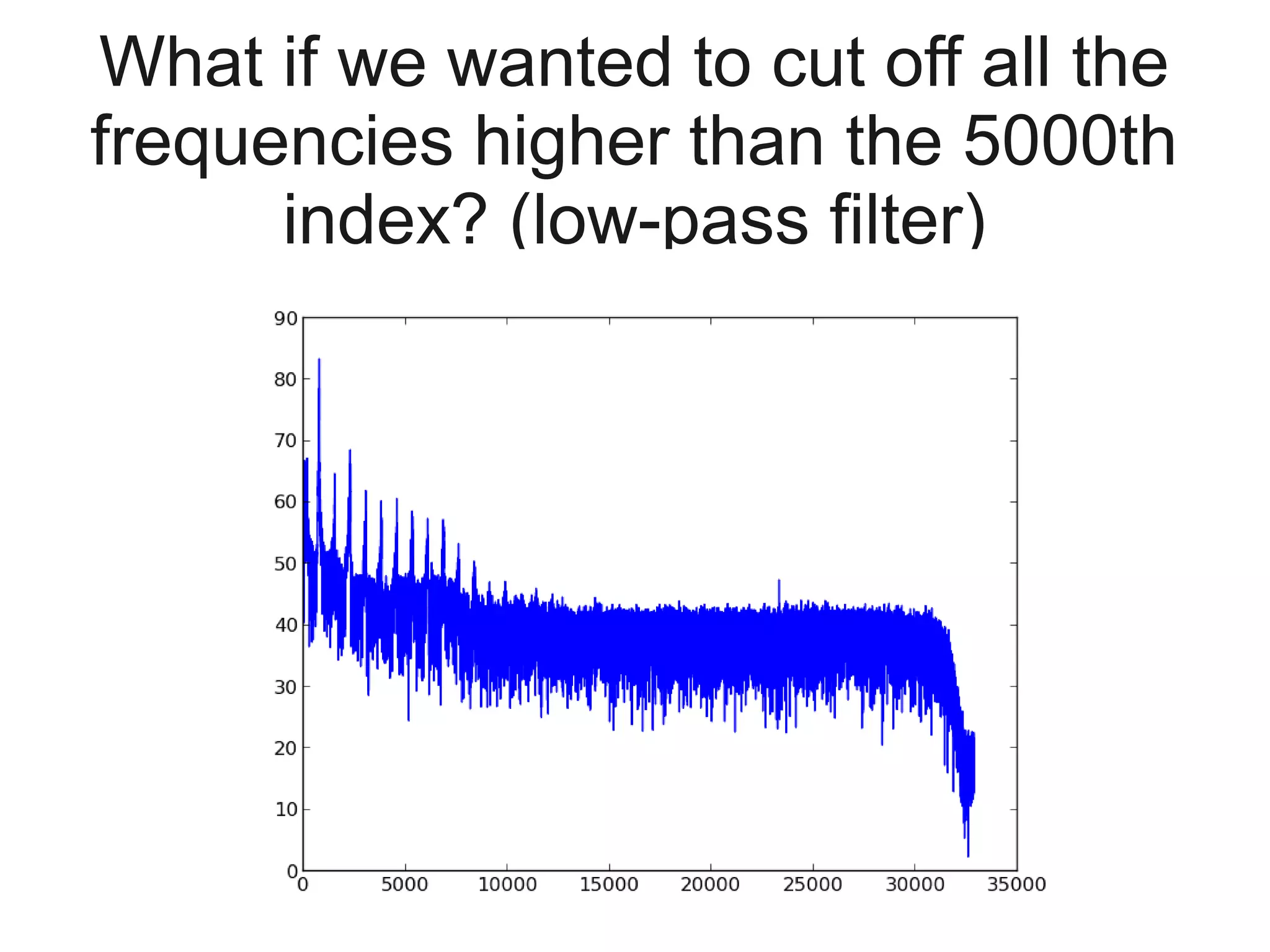

![Implement and plot the low-pass

filter in the frequency domain...

# zero out all frequencies above

# the 5000th index

# (BONUS: what frequency does this

# correspond to?)

flutefft[5000:] = 0

# plot on decibel (dB) scale

makegraph(10*log10(abs(flutefft)),

'flutefft_lowpassed.png')](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sigproc-selfstudy-130318120948-phpapp01/75/Digital-signal-processing-through-speech-hearing-and-Python-63-2048.jpg)