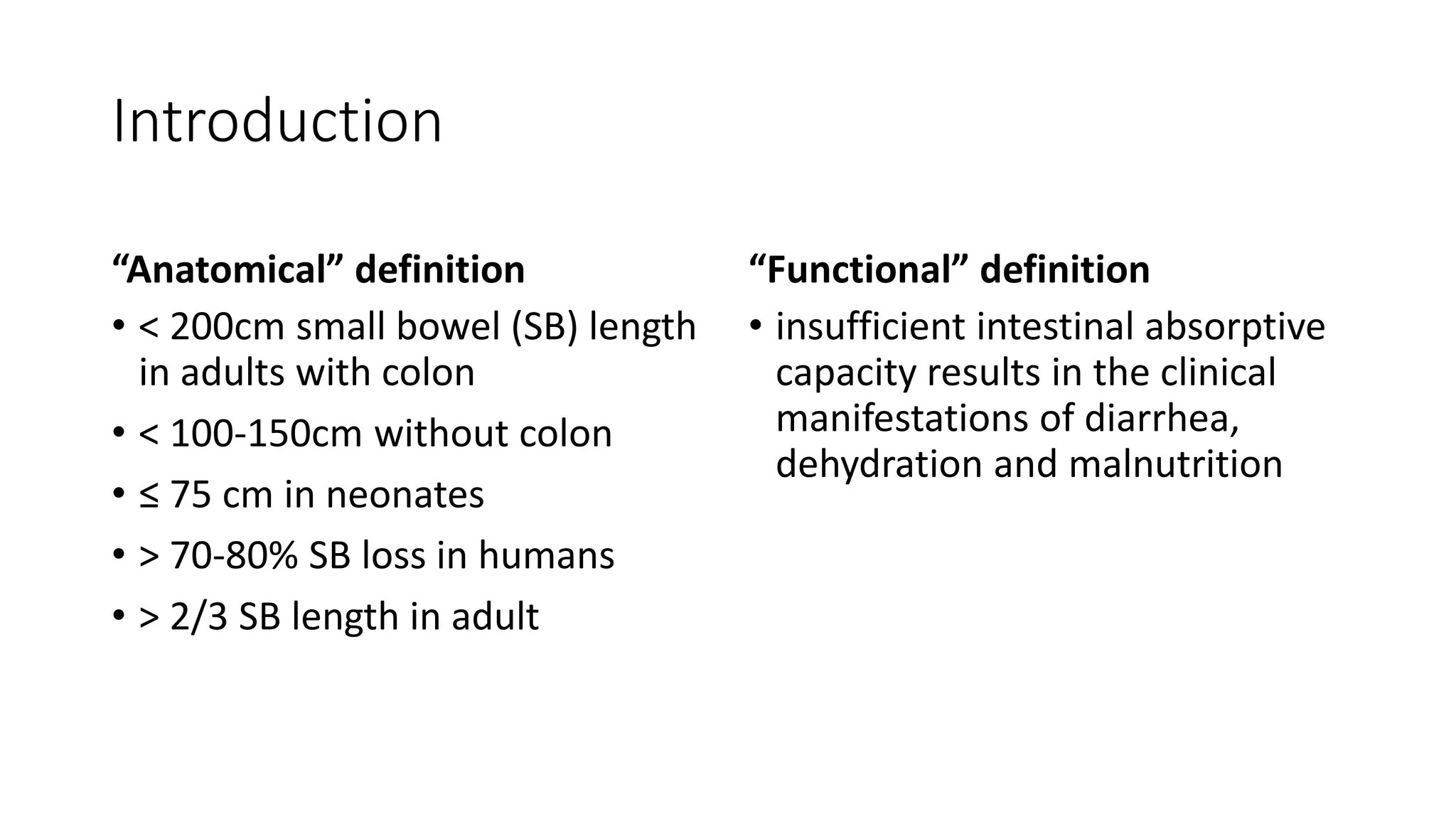

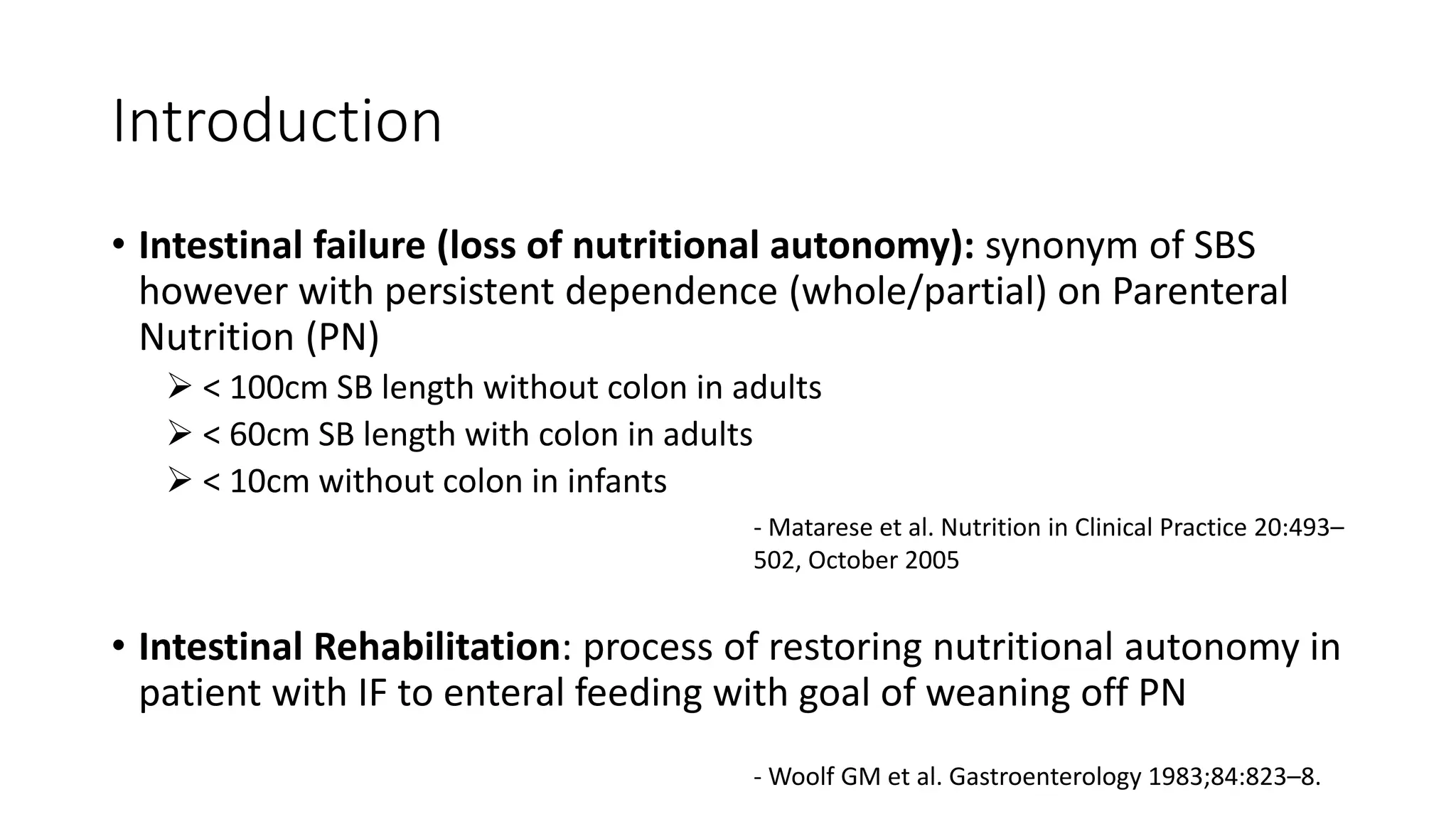

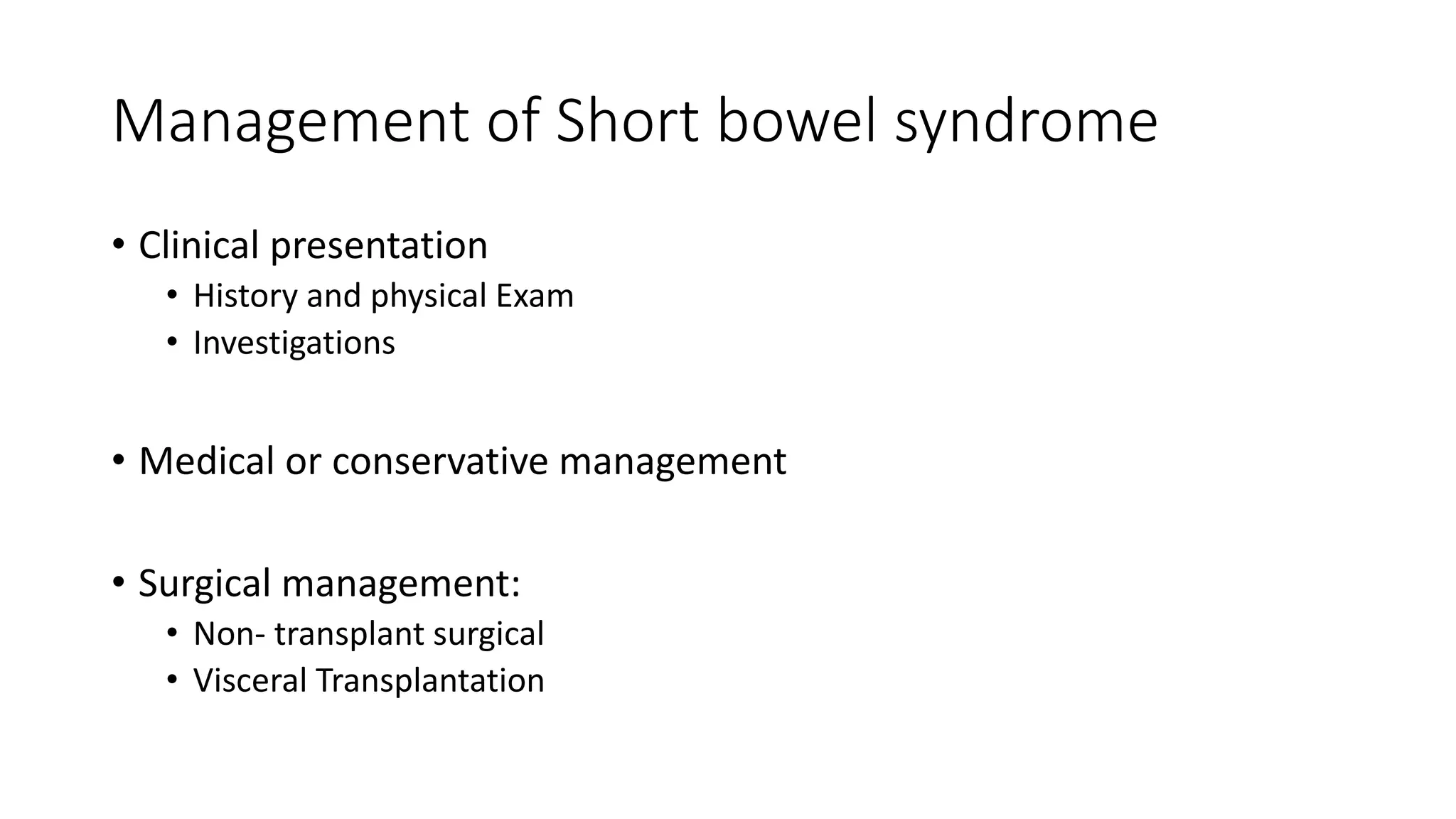

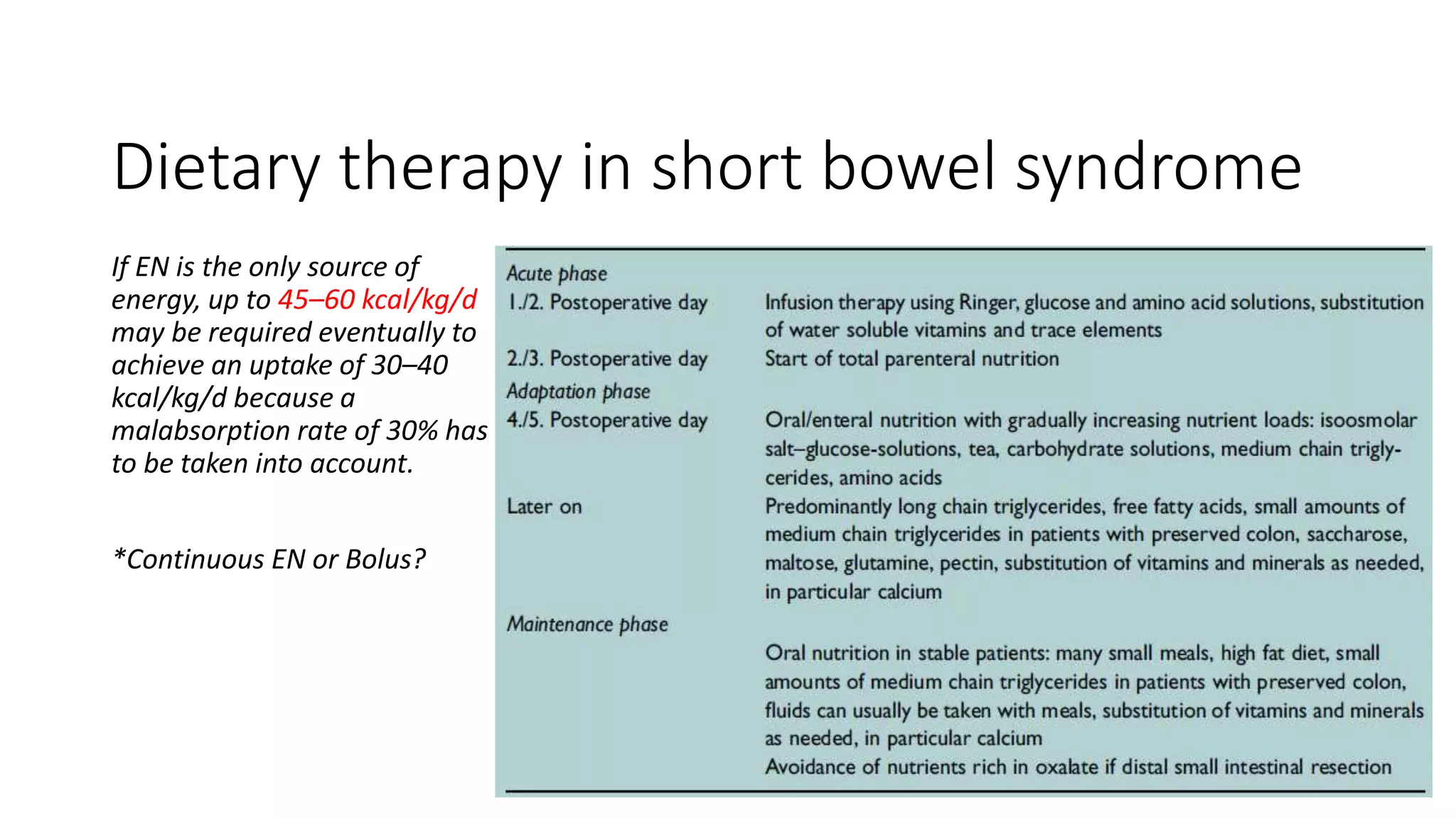

Short bowel syndrome (SBS) results from insufficient intestinal length to support nutrient absorption. It can be defined anatomically as less than 200cm of small bowel length in adults or less than 100-150cm without the colon. The main causes in developing countries are typhoid, intestinal atresias and complications of abdominal surgeries. Management involves nutritional support, medications to reduce diarrhea, and surgical procedures to increase bowel length or function. Advances include intestinal lengthening procedures and intestinal transplantation, but prevention through early management of conditions causing bowel loss remains important.

![References

• Alberti D, Boroni G, Giannotti G, Parolini F, Armellini A, Morabito A, et al. “Spiral

intestinal lenghtening and tailoring (SILT)” for a child with severely short bowel.

Pediatric Surgery International. 2014 Nov;30(11):1169–72.

• Robledo-Ogazón F, Becerril-Martínez G, Hernández-Saldaña V, Zavala-Aznar ML,

Bojalil-Durán L. Anastomosis colónica múltiple en el tratamiento quirúrgico del

intestino corto. Una nueva técnica. Cirugía y Cirujanos. 2008;(1):6.

• Ameh EA. Bowel resection in children. East African Medical Journal [Internet]. 2001

Sep 1 [cited 2018 Aug 28];78(9). Available from:

http://www.ajol.info/index.php/eamj/article/view/8979

• Glick PL, de Lorimier AA, Scott Adzick N, Harrison MR. Colon interposition: An

adjuvant operation for short-gut syndrome. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 1984

Dec;19(6):719–25.

• Sudan D, Thompson J, Botha J, Grant W, Antonson D, Raynor S, et al. Comparison of

Intestinal Lengthening Procedures for Patients With Short Bowel Syndrome: Annals

of Surgery. 2007 Oct;246(4):593–604.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sbspresentation-181216153505/75/Short-Bowel-Syndrome-45-2048.jpg)