This document provides an introduction to fundamental mathematics concepts of sequences, including:

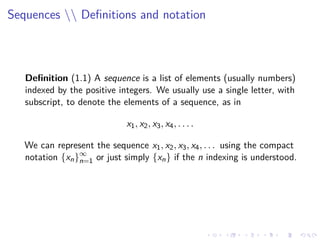

- Sequences are lists of elements indexed by the positive integers. Common notation includes {xn}.

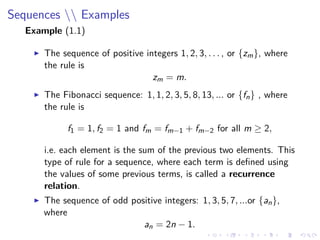

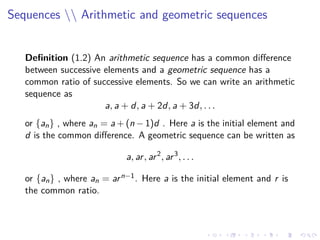

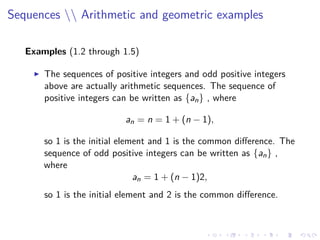

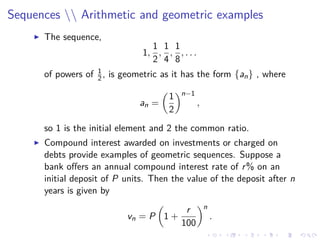

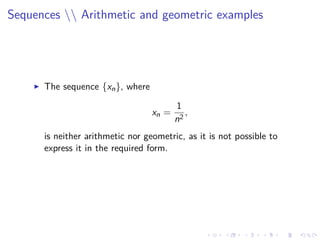

- Examples of sequences include integers, Fibonacci, odds, primes. Arithmetic have a common difference. Geometric have a common ratio.

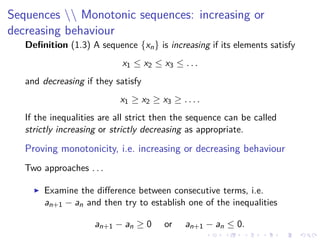

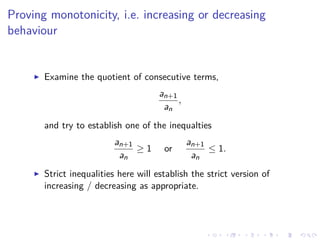

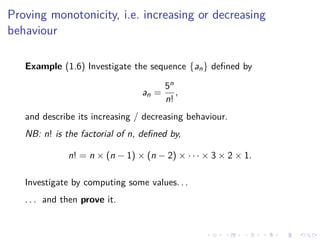

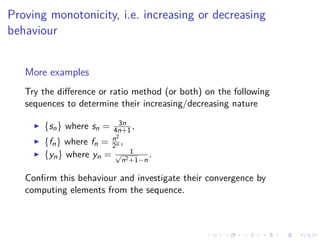

- Monotonic sequences are increasing if x1 ≤ x2 ≤ x3... or decreasing if x1 ≥ x2 ≥ x3.... Proving uses examining differences or ratios of consecutive terms.

- Further examples demonstrate arithmetic, geometric, and proving monotonicity using differences or ratios.