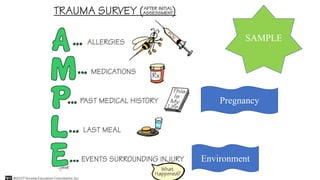

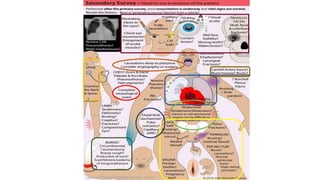

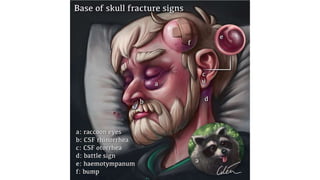

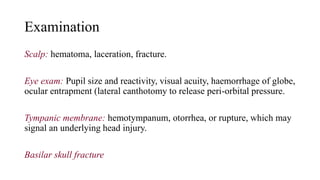

The secondary survey is a thorough head-to-toe examination of a trauma patient to identify any injuries that were not found in the initial primary survey. It should only be performed once resuscitation has begun and the patient's vital signs are stabilizing. The examination involves a detailed history, physical exam of all body systems, and re-evaluation of vital signs. Areas of focus include examination of the head, neck, chest, abdomen, pelvis, extremities, and skin to check for injuries like fractures, bruising, or internal bleeding. The goals are to find any injuries that were overlooked initially and ensure the patient is stabilized before further diagnostic evaluation or treatment.