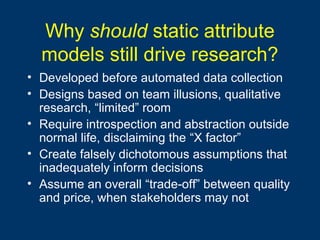

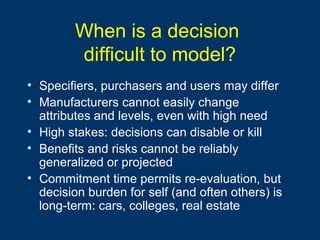

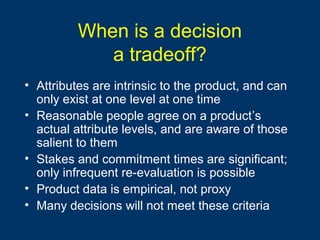

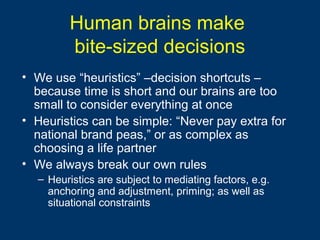

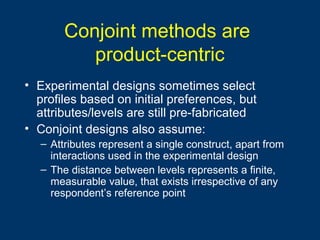

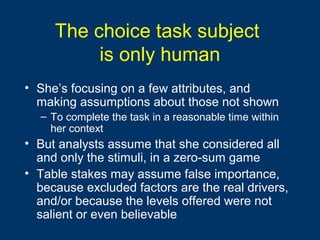

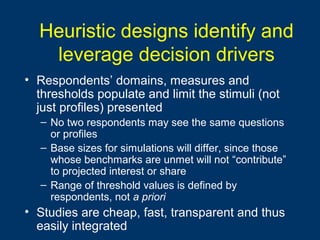

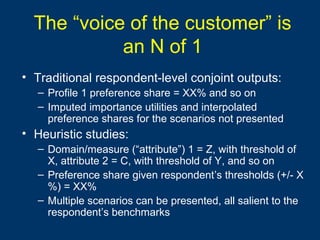

The document discusses the limitations of traditional decision-making models in product development, emphasizing that static attribute models can create misleading trade-offs and ignore the complexities of real-life decision-making. It advocates for heuristic questionnaire designs to better capture individual consumer decisions and preferences, acknowledging that stakeholders operate under different contexts and information constraints. Such heuristic designs can enhance decision support by identifying barriers to information-seeking and validating user needs across various perspectives.