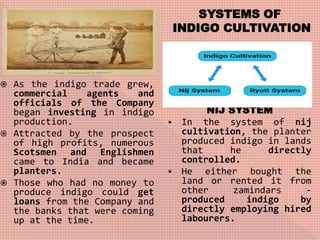

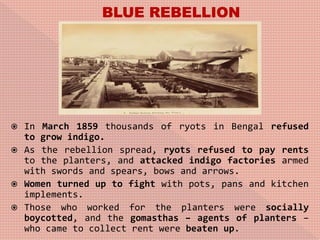

The document summarizes the impact of British policies on agriculture in India. It discusses how the East India Company became the Diwan of Bengal in 1765 and imposed policies that disrupted local economies and led to famine. The British later introduced different land revenue systems, including the Permanent Settlement (1793), the Mahalwari system (1822), and the Ryotwari system. These systems often imposed unsustainable revenue demands that caused peasants to flee their villages. The document also discusses how the British pushed cultivation of commercial crops like opium and indigo through coercion. Indigo cultivation in Bengal expanded in the late 18th century but the Ryoti system used by planters trapped cultivators in debt. This led