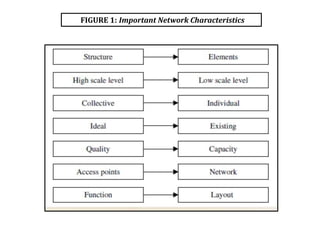

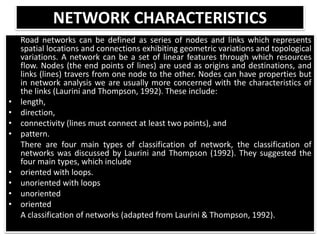

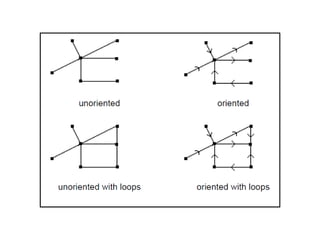

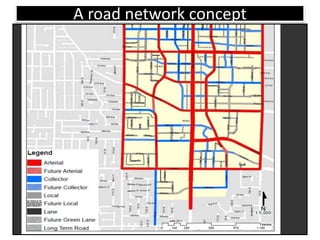

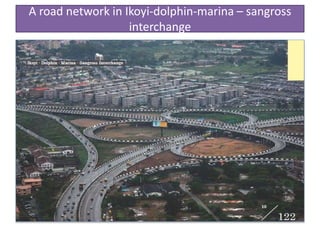

The document provides an overview of road networks and transportation systems. It discusses the importance of roads for trade and mobility in Nigeria. It then covers different aspects of road networks such as their classification, hierarchy, design methods, characteristics, control and operations. The conclusion emphasizes that well-developed transportation infrastructure is crucial for socioeconomic development.