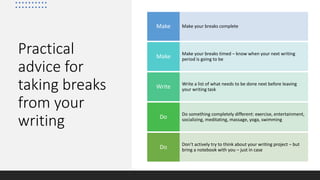

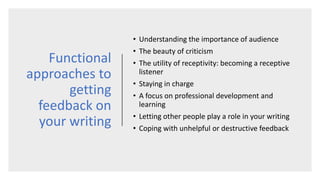

Retreating from academic writing involves three key dimensions: relaxing and resting from writing tasks; re-evaluating one's work by revisiting it and getting feedback from others; and preparing for the next phase of writing. It is an essential part of the writing process that allows writers to detach from their work, reflect on it objectively, and recharge before continuing. Effective strategies for retreating include taking complete breaks from writing for several days; getting feedback from writing partners; and using that feedback to strategically re-engage with one's work in a productive way.

![Retreating in

order to rest

1. There does come a stage in academic

writing tasks when constant, relentless

engagement in your writing is simply

unproductive.

2. This stage encourage you to nurture the

skill of switching off completely

3. Productive, successful writers, and those

who derive more pleasure out of writing.

4. We need strategies for taking our breaks.

5. Turk and Kirkman (1998) advise: ‘try to

leave [your writing] for a few days, or at

least overnight . . .](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentationchapter4-201128091703/85/Retreating-your-writing-6-320.jpg)