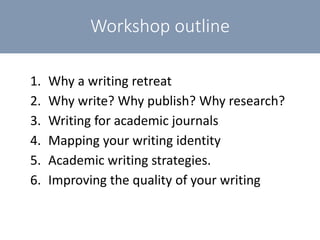

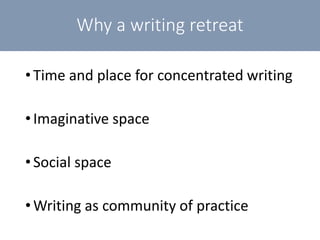

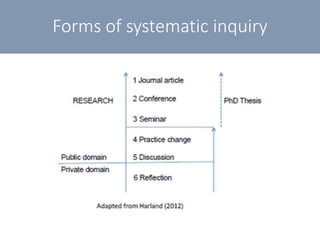

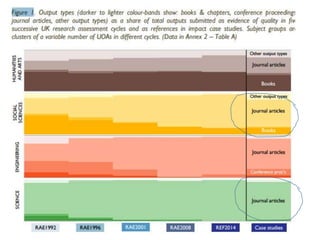

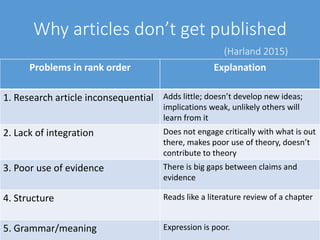

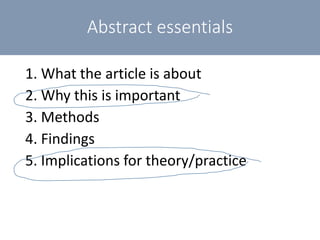

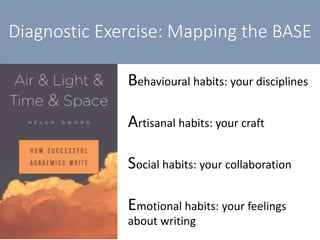

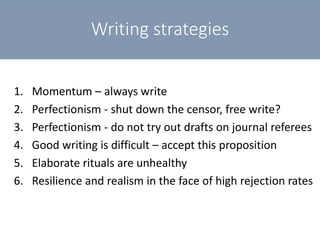

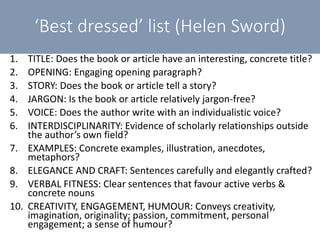

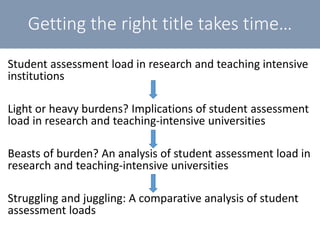

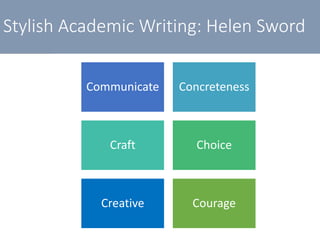

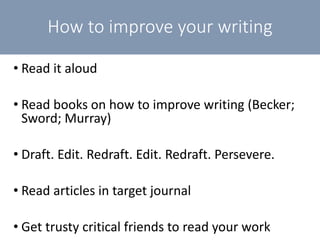

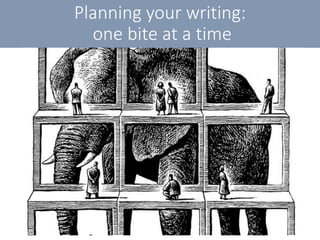

The document outlines the importance and structure of writing retreats aimed at academics to enhance their writing skills and productivity. It emphasizes the necessity of writing for academic growth, publication, and research development while offering strategies for improving writing quality and overcoming common challenges. Furthermore, it discusses the emotional and social aspects of writing, advocating for community support and structured practices to foster better writing habits.