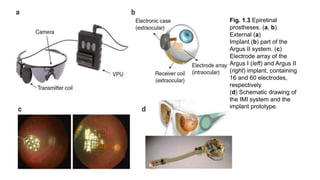

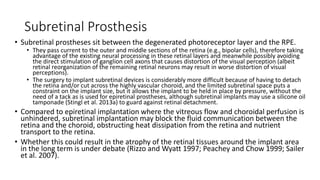

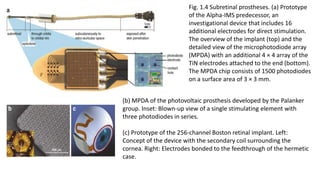

Retinal prostheses are implantable devices designed to restore vision in patients with retinal diseases that have destroyed photoreceptors. The document describes three types of retinal prostheses - epiretinal, subretinal, and suprachoroidal - based on their implantation site. It provides details on the design, surgical procedure, and clinical outcomes of some specific retinal prosthesis devices, including the Bionic Vision Australia suprachoroidal implant and the Retina Implant Alpha-IMS subretinal implant. Complications of retinal prostheses are also discussed.

![Introduction

• Retinal prostheses are implantable devices designed to supplant

phototransduction within the eyes of individuals with significant retinal diseases

such as retinitis pigmentosa.

• In the normal eye, photoreceptors located within the outer layers of the retina

contain light-sensitive pigment that trigger the phototransduction cascade to

generate neuronal signals in the presence of light stimuli.

• These signals are passed to and processed by a complex network of neurons within the middle

layers of the retina before reaching the retinal ganglion cells (RGC) RNFL Visual cortex.

• In congenital retinal dystrophies such as retinitis pigmentosa,

• the outer layers of the retina where photoreceptors reside are gradually lost, thereby causing

progressive visual loss.

• However, inner retinal layers including RGCs are partially spared.[1]

• In theory then, restoration of vision may be achieved by creating devices, retinal prostheses,

that receive and process incoming light and then transmit the information in the form of

electrical impulses to the remaining inner retinal layers for visual function.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/retinalprosthesis-200201162939/85/Retinal-prosthesis-2-320.jpg)

![Results

• Three subjects with light perception visual acuity due to outer retinal degenerative

diseases (2 with rod-cone dystrophy, 1 with syndromic retinitis pigmentosa) were

implanted with suprachoroidal retinal prosthesis devices and percutaneous

connectors.

• Post-surgical hemorrhage in the subretinal and suprachoroidal spaces was noted in all

subjects, but in each case spontaneously resolved without further complications.

• Device stability and integrity was measured regularly using fundus photography,

infrared imaging, OCT, and impedance studies.

• Imaging showed no movements of the device, but distance from the device to the RPE

markedly increased over the course of the year in two subjects [roughly 600 µ to 900 µ ]

• Impedance studies showed significantly decreased micro-electrode impedance in one subject

over time which was thought to be due to changes in the electrode-tissue interface.

• All 3 subjects scored significantly better with the device on than with it off in the

• Visual acuity was estimated to be logMAR 2.62 (20/8397) on average with the device on.

• With the device off, the same subject was unable to see any Landolt-C optotypes.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/retinalprosthesis-200201162939/85/Retinal-prosthesis-22-320.jpg)

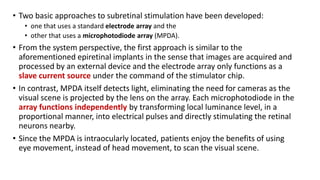

![Fundus photo of Retina Implant Alpha-

IMS device

The Alpha-IMS is a subretinal, micro-photodiode array retinal

prosthesis developed by Retina Implant AG in Reutlingen,

Germany and approved in Europe in 2013.

It is designed to be implanted in the layer of degenerated

photoreceptor cells in patients with degenerative outer retinal

disease.

Consequently, electrical impulses from the device stimulate

bipolar cells in the middle retinal layers which carry the signals

to RGCs.

An earlier version of the device with a retroauricular transdermal

cable connected the device to an external battery and was

implanted in 11 blind volunteers beginning in 2005. After positive

visual function outcomes, a wireless version was developed

which is currently undergoing single and multi-center clinical trials

in Europe.[18]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/retinalprosthesis-200201162939/85/Retinal-prosthesis-24-320.jpg)

![Surgical technique

• Surgical implantation consists of extra- and intra-ocular procedures which may be performed

consecutively over 6-8 hours.

• The extraocular procedure begins with a 4 cm arcuate, retroauricular incision and a secondary,

horizontal incision of about the same size crossing the first. A raspatory is used to dissect down

to the bone to expose an approximately 2 cm by 2 cm square of retroauricular bone upon and

then a standard otologic drill is used to make a 3-4 mm deep implant bed for the ceramic casing

containing electronics. Another incision is made near the lateral orbital rim over the margo

orbitalis and the zygomatic-frontalis suture is exposed by elevating the periosteum.

• Intraorbital periosteum is also elevated to allow for an L-shaped canal to be drilled. A complete

peritomy is performed at the limbus, and a tunnel is dissected from the subconjunctival space to

the orbital rim incision.

• A silicone tube is inserted to keep it patent. Next, a 15 cm long, raspatory is used to tunnel

beneath the periosteum of the temporal bone to connect the orbital rim incision with the

retroauricular site.

• Then, a custom, hollow trocar is inserted anteriorly beneath the temporal periosteum and

extended through to the retroauricular incision site. The power cable and subretinal implant

components, protected by a silicone tube, are pulled from the retroauricular site to the orbital

rim using the trocar and then inserted through the tunnel to the subconjunctival space. Prior to

the intraocular procedure, electrical testing of the implant is performed. The extraocular surgery

takes approximately 60-80 minutes.[20][21]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/retinalprosthesis-200201162939/85/Retinal-prosthesis-26-320.jpg)

![• To begin the intraocular procedure, a standard pars-plana victretomy is

performed and then a 1 by 4 mm scleral flap made 9 mm posterior to the

limbus in the supero-temporal quadrant. The retina is elevated by injecting

balanced saline solution or Healon. Then, a guiding tool is inserted through

the sclera and choroid to a subretinal position between the choroid and the

retina.

• Correct insertion and positioning of the guiding tool may be aided by

calculating the optimal angle and distance of insertion and making a line

between an insertion point and reference point marked by a corneal marker.

• Insertion depth may be calculated and tracked by calibration lines on the

guidance tool. The polyimide foil is then introduced along the path of the

guiding foil to the subretinal space.

• The outside end of the foil is connected to a sealed ceramic connector piece

which is sutured onto the sclera. Finally a macular hole is created by

separating the pigment epithelium layer from the neuroretina and the array is

placed according to planned positioning as seen on fundus images prior to

surgery.[20][22]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/retinalprosthesis-200201162939/85/Retinal-prosthesis-27-320.jpg)

![• Alpha-IMS devices have been implanted in at least 29 participants within single and multi-center

modules as a part of an ongoing clinical trial by Zrenner and colleagues.[18] Those receiving implants

had either no light perception or light perception without projection due to degenerative outer

retinal diseases (25 had retinitis pigmentosa, 4 had cone-rod dystrophy) prior to implantation.

• Of the 29 participants, at least two serious adverse events have been reported – one increase of

intraocular pressure up to 46 mmHg and the other a retinal detachment immediately after

explantation of the device.[23] Both were treated and managed without long-term sequelae.

• Notably, after implantation 4 of the 29 subjects could not perceive any light while the device was

turned on. Though the cause was unclear, the Stingl et al. attributed this result to either failure of

the device in vivo or to sequelae of the implantation surgery such as inflammation of the optic

nerve or retina.[18]

• The following results are a summary of visual function test performances of 29 implanted subjects

described by Stingl and colleagues in their 2015 clinical trial interim report.

• According to the interim report, subjects with the Alpha-IMS turned on were significantly more

likely to correctly perceive and localize flashes of light on a screen 60 cm away than with the device

turned off, but there was no significant difference in ability to recognize the direction of movement

of the flashes. These tests were performed according to the Basic Assessment of Light and Motion

which has been described previously.

• With the device on, subjects were also significantly more likely to correctly tell the orientation of a

grating than with it off, but no significant difference was seen when testing acuity with Landolt C-

rings. Of the 4 subjects who passed the Landolt C-ring test, one passed with a visual acuity of

20/546.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/retinalprosthesis-200201162939/85/Retinal-prosthesis-28-320.jpg)

![• The EPIRET3 system was designed by the EPI-RET Project group in

Germany to be a wirelessly controlled, epiretinal device.

• Electrical impulses are transferred to the retina by 25, 100 micrometer diameter

electrodes arrayed in a hexagonal pattern coated in a thin film of iridium oxide

and affixed to the end of a via a 40 mm long, 3 mm wide polyimide foil micro-

cable which connects the electrodes to a receiver module implanted within the

lens capsule.

• The receiver module consists of a receiver coil that wirelessly obtains transmitted

data, a receiver chip that processes that data, and a stimulation chip that

generates and sends impulse activation patterns to the micro-electrode array. The

entire implant is coated with parylene C for biocompatibility.[29] The internal coil

receives temporospatial data and power wirelessly from an external coil and

transmitter unit attached to glasses in front of the eye. Data and power originate

from a portable computer system worn or carried by the user.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/retinalprosthesis-200201162939/85/Retinal-prosthesis-40-320.jpg)

![Results

• Successful experimental implantation and explantation of the EPIRET3

system in 6 subjects was reported in 2009 by Roessler and colleagues.

• Per ethics guidelines, the devices remained in the eyes for only 28 days before

explantation.

• Subjects all carried diagnoses of retinitis pigmentosa confirmed by ERG and had

visual acuities ranging from no light perception (1/6 patients) to light perception

(4/6) to hand movements (1/6).

• No severe adverse events were reported in any of the subjects. However, one

patient developed culture-negative hypopyon on post-implantation day 3 which

was treated and cleared by day 5.

• During explantation, a different subject developed a macular hole which

was filled with silicone oil. Although minor gliosis was visible on

angiography near tack sites, visual acuity was stable at long-term follow-

up for all patients.[28][30]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/retinalprosthesis-200201162939/85/Retinal-prosthesis-42-320.jpg)

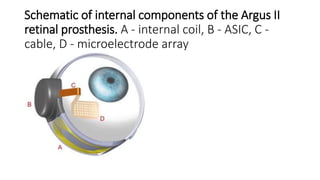

![Design

• The Argus® II is a second-generation epiretinal, micro-electrode array retinal

prosthesis developed and sold by Second Sight Medical Products.

• It recently was approved for marketing in both Europe (2011) and the United

States (2013), being the first device to gain that distinction.

• Its design differs from the first generation model, the Argus I, in the number and

spacing of microelectrodes on the array (6x10 instead of 4x4), the placement of

internal processing components (sutured onto the sclera instead of subcutaneous

placement inside the temporal recess), and the placement of the external

transmission coil (built into the sidearm of the glasses instead of held magnetically by

the internal components over the temporal bone).[8]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/retinalprosthesis-200201162939/85/Retinal-prosthesis-45-320.jpg)