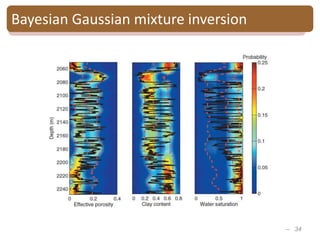

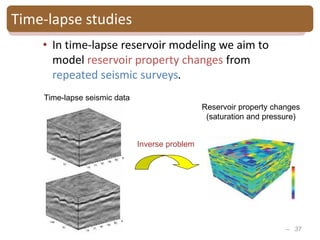

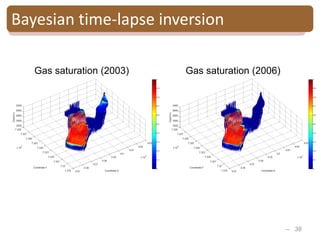

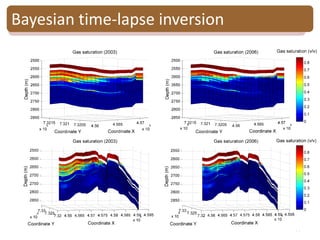

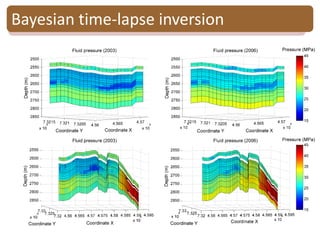

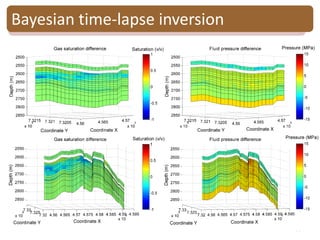

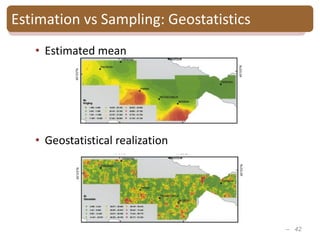

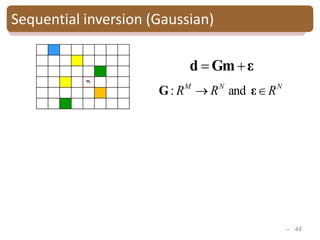

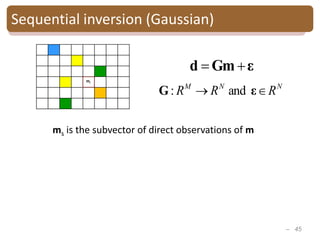

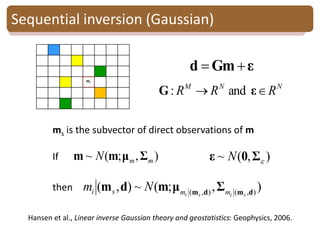

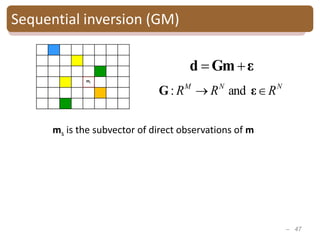

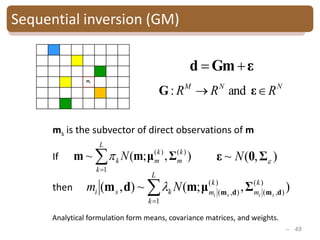

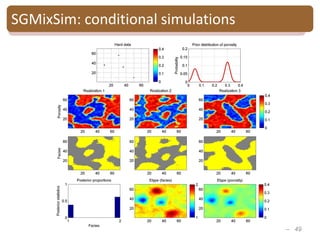

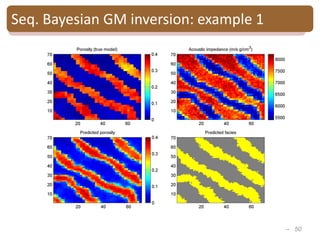

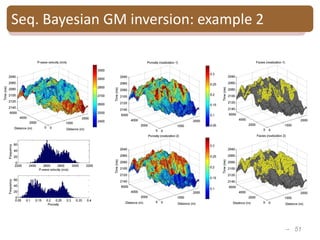

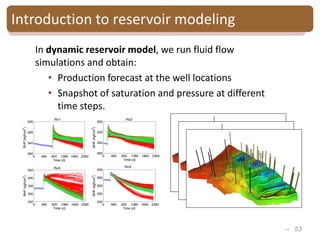

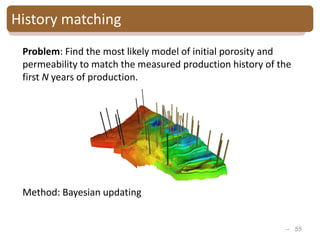

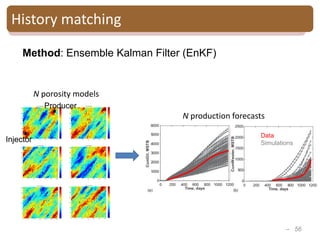

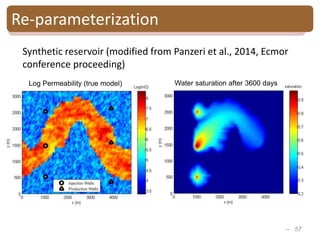

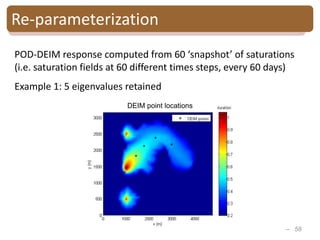

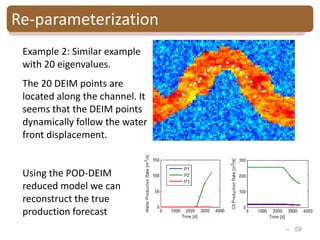

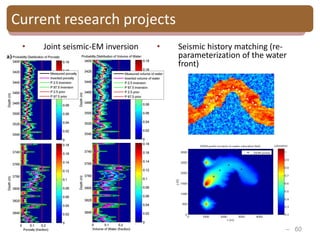

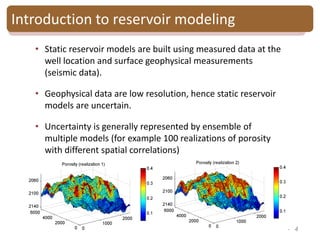

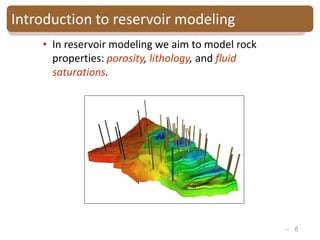

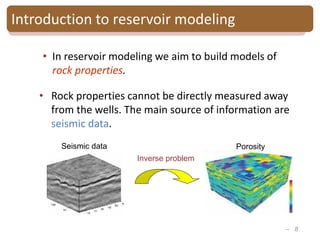

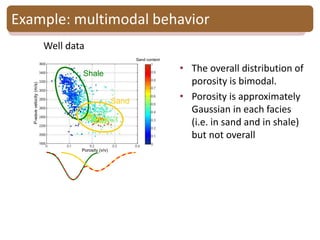

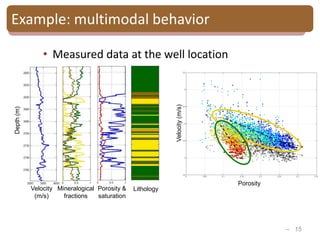

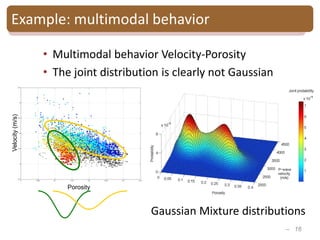

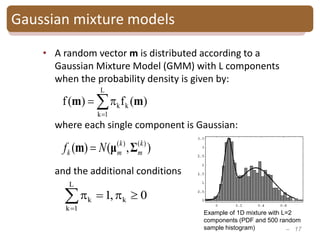

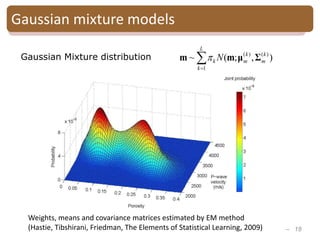

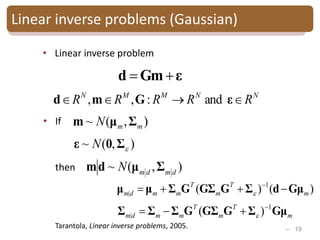

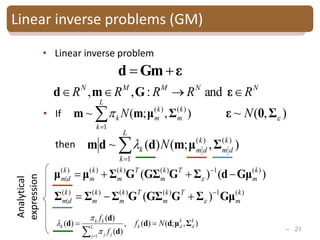

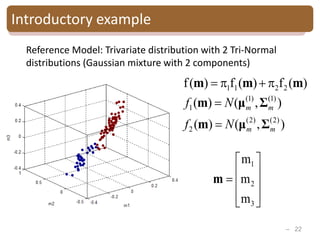

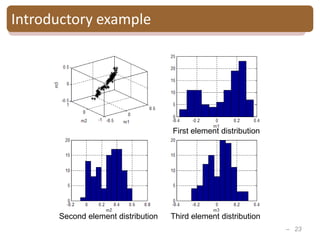

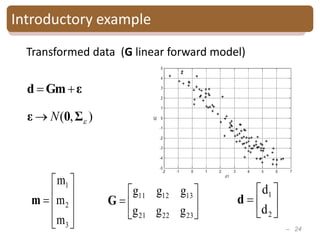

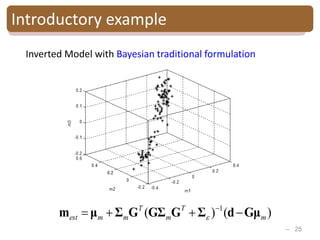

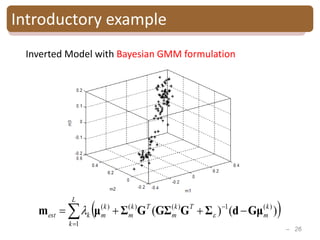

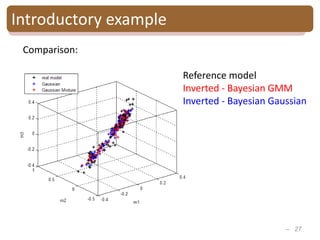

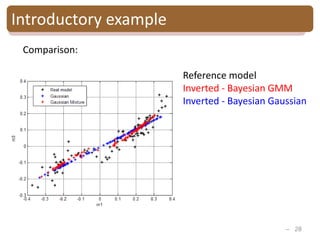

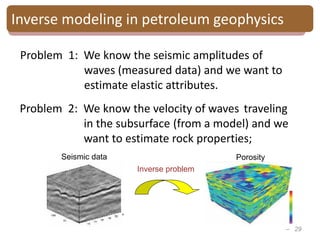

The document provides an introduction to Bayesian inverse theory and its applications in subsurface characterization and reservoir modeling. It discusses how Bayesian inversion can be used to estimate reservoir properties like porosity and saturation from seismic data by treating the inverse problem as estimating the posterior distribution given prior information and measurements. It also describes how the method can be extended to handle multimodal distributions using Gaussian mixture models. Further applications discussed include time-lapse inversion to estimate property changes over time and history matching to update reservoir models based on production data.

![– 30

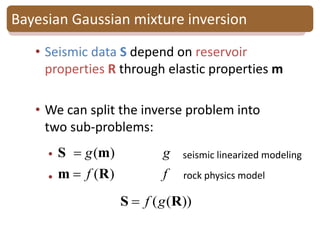

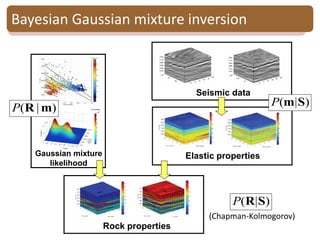

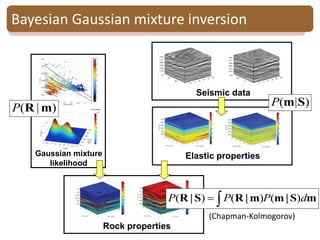

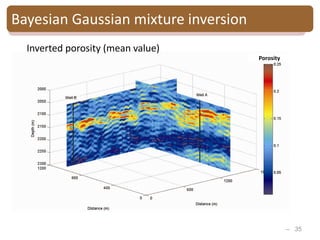

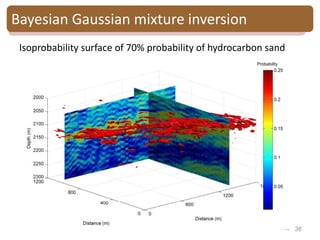

Bayesian Gaussian mixture inversion

• Goal: - Estimate reservoir properties R

from seismic data S

-Evaluate the model uncertainty

)](),(),([

],,[

)|(

321

SSS

swc

P

S

R

SR

Porosity

Clay content

Water saturation

Partial-stack

seismic data

We estimate the posterior probability:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/quebec-150403112446-conversion-gate01/85/Reservoir-Modeling-30-320.jpg)