This document discusses using relations and relational calculus to specify programs in a more natural way. It proposes enhancing data types with invariants to tame non-determinism and partiality in relational specifications. This allows inferring checkable domain and range predicates for relations to optimize execution. Bidirectional transformations are also specified relationally to maximize updatability.

![Introduction

Relational Calculus

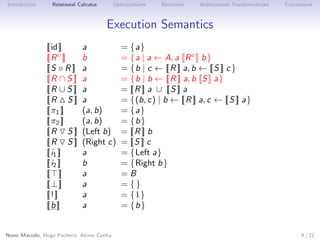

Optimizations

Recursion

Bidirectional Transformations

Conclusions

Motivating Example

(id

id)◦ ◦ (head◦

length◦ ) : Nat → [Nat]

• Calculates a list with length n and the same n at its head;

• Not total nor functional;

• Very inefficient given a naive semantics;

• head◦ could be generating all lists by increasing length and

never reach n.

(id4id)

(id4id)

Nuno Macedo, Hugo Pacheco, Alcino Cunha

head 4length

(head 4length )

3 / 21](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ndlenses-ramics-slides-140226100759-phpapp02/85/Relations-as-Executable-Specifications-3-320.jpg)

![Introduction

Relational Calculus

Optimizations

Recursion

Bidirectional Transformations

Conclusions

Motivating Example

• We can predict the behavior of partial expressions by

calculating the exact domain and range;

• They can also be used to narrow non-deterministic executions.

●{(l, l0 ) 2 [Nat] ⇥ [Nat]|head l = length l0 ^ l = l0 }

(id4id)

●{l 2 [Nat]|head l = length l}

Nuno Macedo, Hugo Pacheco, Alcino Cunha

(id4id)

head 4length

(head 4length )

●{n 2 Nat|n 6= 0}

4 / 21](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ndlenses-ramics-slides-140226100759-phpapp02/85/Relations-as-Executable-Specifications-4-320.jpg)

![Introduction

Relational Calculus

Optimizations

Recursion

Bidirectional Transformations

Conclusions

Predicates as Coreflexives

• Domain δR and range ρR are predicates that can be defined

as coreflexives;

• Coreflexives Φ : A → A are relations smaller than the identity;

• If a satisfies the predicate Φ then a Φ a;

• For pairs A × B related by R : A → B, the invariant is lifted as

[R] : A × B → A × B;

• Invariants on coproducts are simply the coproduct Φ + Ψ;

• R : Φ → Ψ denotes δR = Φ and ρR = Ψ.

Nuno Macedo, Hugo Pacheco, Alcino Cunha

9 / 21](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ndlenses-ramics-slides-140226100759-phpapp02/85/Relations-as-Executable-Specifications-9-320.jpg)

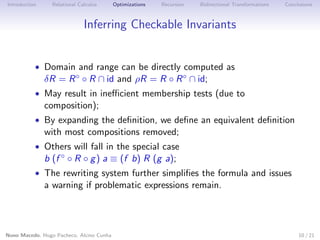

![Introduction

Relational Calculus

Optimizations

Recursion

Bidirectional Transformations

Conclusions

Example

(id

id)◦ ◦ (head◦

length◦ ) : Nat → [Nat]

ρ((id id)◦ ◦ (head◦ length◦ ))

={Range definition}

ρ((id id)◦ ◦ ρ(head◦ length◦ ))

={Range definition}

ρ((id id)◦ ◦ [length◦ ◦ head])

={Range definition}

δ([length◦ ◦ head] ◦ (id id))

={Domain definition, Simplifications : PF Laws}

(head◦ ◦ length) ∩ id

(id id)◦ ◦(length◦ head◦ ):inN ◦(⊥+id)◦outN → (head◦ ◦length)∩id

Nuno Macedo, Hugo Pacheco, Alcino Cunha

11 / 21](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ndlenses-ramics-slides-140226100759-phpapp02/85/Relations-as-Executable-Specifications-11-320.jpg)

![Introduction

Relational Calculus

Optimizations

Recursion

Bidirectional Transformations

Conclusions

Optimizing Non-deterministic Executions

• After determining the domain and range, they can be

propagated down to primitives,

• This reduces the generation of irrelevant intermediate values;

| id : Φ → Ψ | a = | Ψ | a

| π1 : [U ] → Ψ | (a, b) = | Ψ | a

| R ◦ S : Φ → Ψ | a = {b | c ← | S : Φ → δR | a,

b ← | R : ρS → Ψ | c }

| R ∩ S : Φ → Ψ | a = {b | b ← | R : Φ ∩ δS → ρ(Ψ ◦ S ◦ a) | a}

Nuno Macedo, Hugo Pacheco, Alcino Cunha

12 / 21](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ndlenses-ramics-slides-140226100759-phpapp02/85/Relations-as-Executable-Specifications-12-320.jpg)

![Introduction

Relational Calculus

Optimizations

Recursion

Bidirectional Transformations

Conclusions

Recursive Relations: Example

unzip : [A × B ] → [A] × [B ]

ρunzip

={Range definition}

(unzip ◦ unzip◦ ) ∩ id

={Simplifications : unzip is functional, Liftify : range of unzip is a product}

◦

[π2 ◦ unzip ◦ unzip◦ ◦ π1 ]

={Catamorphism fusion : π1 ◦ g = nil (cons ◦ (π1 × id)) ◦ F π1 }

[(

|nil (cons ◦ (π1 × id))| ◦ (

) |nil (cons ◦ (π2 × id))| ◦ ]

)

={Definitions : map}

[(map π1 ) ◦ (map π2 )◦ ]

={Simplifications : map converse, map fusion (see below )}

◦

[map (π1 ◦ π2 )]

={Simplifications : PF Laws}

[map ]

unzip : id → [map

Nuno Macedo, Hugo Pacheco, Alcino Cunha

]

14 / 21](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ndlenses-ramics-slides-140226100759-phpapp02/85/Relations-as-Executable-Specifications-14-320.jpg)

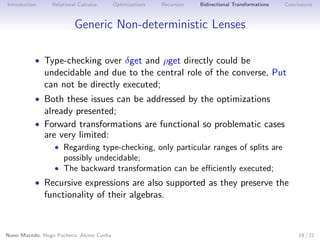

![Introduction

Relational Calculus

Optimizations

Recursion

Bidirectional Transformations

Conclusions

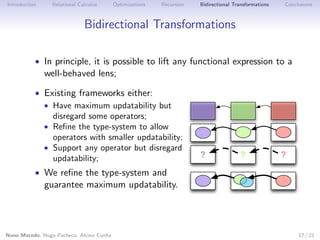

Generic Non-deterministic Lenses

• Using relational calculus we can define a generic Put that is

the largest relation that satisfies the properties;

• A transformation get : A → B can be lifted to a well-behaved

non-deterministic lens get : δget

Put = (π2

ρget, with

(get◦ ◦ π1 )) ◦ [get◦ ] ?

• Emerges naturally from the lens laws:

• [get◦ ] ? (v , s) tests if v was changed, returning either the

original s (acceptability), or any source s such that s = get v

(stability);

• Maximum updatability: δPut = ρget × δget.

Nuno Macedo, Hugo Pacheco, Alcino Cunha

18 / 21](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ndlenses-ramics-slides-140226100759-phpapp02/85/Relations-as-Executable-Specifications-18-320.jpg)

![Introduction

Relational Calculus

Optimizations

Recursion

Bidirectional Transformations

Conclusions

Generic Non-deterministic Lenses: Example

π1

id : id

◦

[π1 ]

◦

• The range is [π1 ] : A × (A × B) → A × (A × B), so Put only

takes views (a, (b, c)) where a ≡ b;

◦

id)◦ will run, and π1 could

generate all pairs until reaching (a, c);

• When the view is updated, (π1

• With our optimization, the output of π1 is restricted to have c

in the second element.

Nuno Macedo, Hugo Pacheco, Alcino Cunha

20 / 21](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ndlenses-ramics-slides-140226100759-phpapp02/85/Relations-as-Executable-Specifications-20-320.jpg)