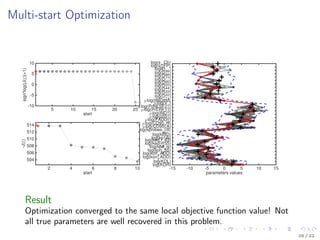

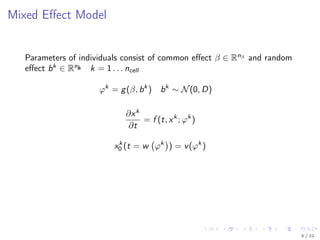

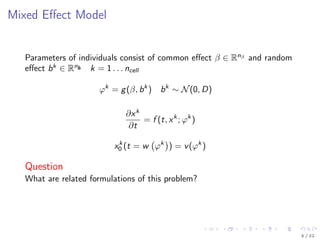

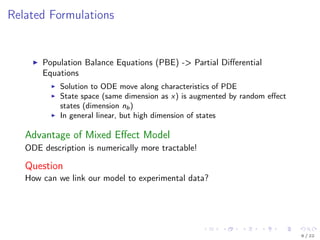

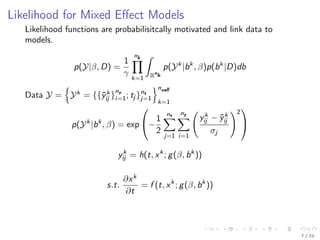

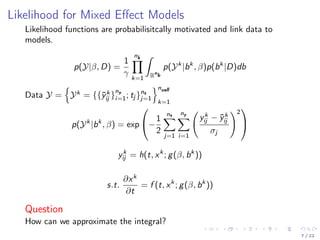

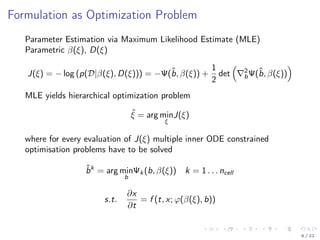

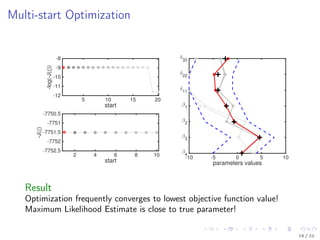

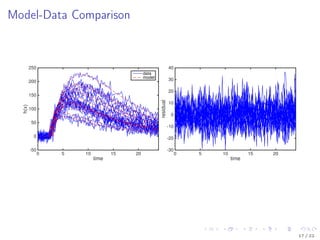

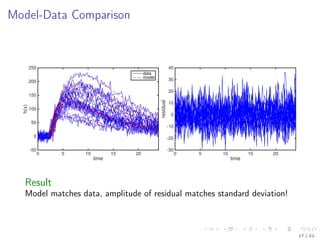

The document discusses parameter estimation for heterogeneous populations using mixed effect models, linking these models to experimental data. It presents applications to GFP transfection data and trail signaling pathways while demonstrating the development of efficient optimization methods to address challenges in estimating parameters. Additionally, it highlights the advantages of mixed effect models in computational tractability and explores various approximation and optimization techniques for parameter estimation.

![Heterogeneity in Structured Populations

Behavior of individuals:

time [h]

0 5 10 15 20

h(x)

-50

0

50

100

150

200

250

3 / 22](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentationff-170806122638/85/Presentation-OCIP-2015-3-320.jpg)

![Heterogeneity in Structured Populations

Behavior of individuals:

time [h]

0 5 10 15 20

h(x)

-50

0

50

100

150

200

250

Question

How can we mathematically describe this system?

3 / 22](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentationff-170806122638/85/Presentation-OCIP-2015-4-320.jpg)

![Laplace Approximation for Integral

Pinheiro [1994] suggests Laplace approximation of integral

p(Y|β, δ) ≈

ncell

k=1

ˆ

Rn

b

exp(−

1

2

Ψk (ˆbk

, β)−

1

2

(bk

−ˆbk

)T 2

bΨk (ˆbk

, β)(bk

−ˆbk

))dbk

where

Ψk (b, β, D) = −2 log p(Yk

|b, β)p(b, D)

s.t ˆbk

= arg min

b

Ψk (b, β, D) .

This approximation yields

p(Y|β, D) ≈

ncell

k=1

exp −

1

2

Ψk (ˆbk

, β) +

1

2

log (2π)nb det 2

bΨk (ˆbk

, β) .

8 / 22](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentationff-170806122638/85/Presentation-OCIP-2015-14-320.jpg)

![Laplace Approximation for Integral

Pinheiro [1994] suggests Laplace approximation of integral

p(Y|β, δ) ≈

ncell

k=1

ˆ

Rn

b

exp(−

1

2

Ψk (ˆbk

, β)−

1

2

(bk

−ˆbk

)T 2

bΨk (ˆbk

, β)(bk

−ˆbk

))dbk

where

Ψk (b, β, D) = −2 log p(Yk

|b, β)p(b, D)

s.t ˆbk

= arg min

b

Ψk (b, β, D) .

This approximation yields

p(Y|β, D) ≈

ncell

k=1

exp −

1

2

Ψk (ˆbk

, β) +

1

2

log (2π)nb det 2

bΨk (ˆbk

, β) .

Question

What is the corresponding inverese problem?

8 / 22](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentationff-170806122638/85/Presentation-OCIP-2015-15-320.jpg)

![Properties of J(ξ)

The objective function J(ξ) in general

is non-convex

is computationally expensive to evaluate

is sufficiently smooth

Proprietary implementations [Gibiansky et al., 2012] exist but

are not extendable

do not cover all desirable features

Local gradient based methods perform well in many ODE constrained

optimization problems [Raue et al., 2013]

→ Develop an efficient local gradient based optimization schemes for

mixed effect models

10 / 22](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentationff-170806122638/85/Presentation-OCIP-2015-17-320.jpg)

![Properties of J(ξ)

The objective function J(ξ) in general

is non-convex

is computationally expensive to evaluate

is sufficiently smooth

Proprietary implementations [Gibiansky et al., 2012] exist but

are not extendable

do not cover all desirable features

Local gradient based methods perform well in many ODE constrained

optimization problems [Raue et al., 2013]

→ Develop an efficient local gradient based optimization schemes for

mixed effect models

Question

How to compute gradients of J(ξ)?

10 / 22](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentationff-170806122638/85/Presentation-OCIP-2015-18-320.jpg)

![Gradient of x w.r.t. ϕ

For

∂x

∂t

= f (t, x; ϕ)

the derivatives w.r.t. ϕi can be compute via sensitivity equations:

∂

∂t

∂x

∂ϕi

= x f (t, x; ϕ)

∂x

∂ϕi

+

∂f (t, x; ϕ)

∂ϕi

∂

∂t

∂x

∂ϕi ϕj

=

∂x

∂ϕj

T

2

x f (t, x; ϕ)

∂x

∂ϕi

+ x f (t, x; ϕ)

∂x

∂ϕi ∂ϕj

+

∂f (t, x; ϕ)

∂ϕi ∂ϕj

Efficient implementation for the computation of first order sensitivities

are available in CVODES [Serban and Hindmarsh, 2005].

13 / 22](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentationff-170806122638/85/Presentation-OCIP-2015-21-320.jpg)

![Parametrization

∂xk

∂t

=

−ϕk

1x1

ϕk

3x − ϕk

2x

xk

(t = ϕk

4) =

1

0

ϕk

=

exp(β1)

exp(β2 + bk

1 )

exp(β3 + bk

2 )

exp(β4 + bk

3 )

bk

=

bk

1

bk

2

bk

3

∼ N

0

0

0

,

exp(δ11) 0 0

0 exp(δ22) 0

0 0 exp(δ33)

ξ = [ β1 β2 β3 β4 δ11 δ22 δ33 ]

15 / 22](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentationff-170806122638/85/Presentation-OCIP-2015-23-320.jpg)

![Model Description

Kallenberger et al. [2014] introduced a model for the TRAIL signalling

pathway.

This model was extended to account for new experimental data.

Number of parameters nϕ: 21

Number of states nx : 15

Number of observables ny : 6

Number of variable species nb: 8

19 / 22](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentationff-170806122638/85/Presentation-OCIP-2015-29-320.jpg)