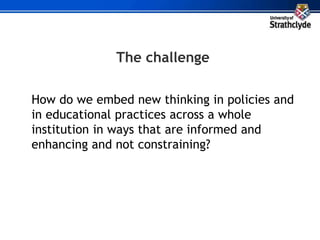

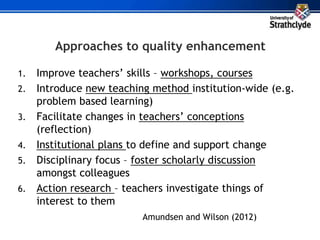

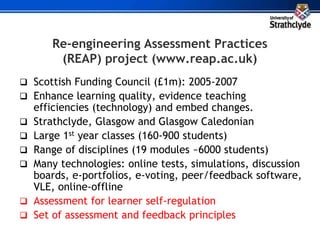

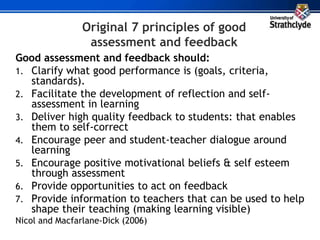

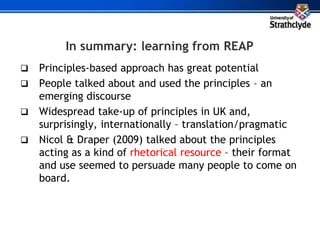

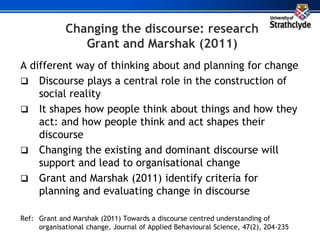

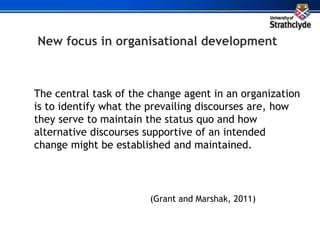

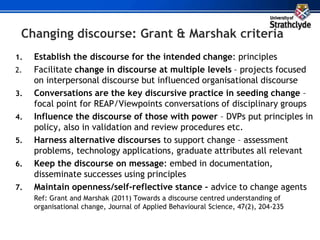

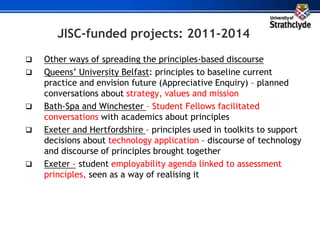

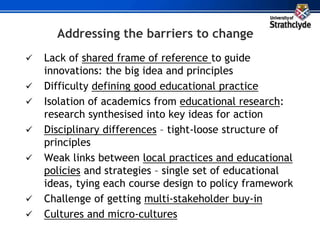

The document discusses the barriers and approaches to enhancing assessment and feedback quality in higher education, emphasizing a principles-led change model. It outlines key principles for effective assessment that promote learner self-regulation, high-quality feedback, and collaborative dialogue between students and teachers. The text also describes successful implementation projects, REAP and Viewpoints, showcasing how these principles were embedded in institutional practices to foster a transformative educational discourse.

![Good assessment and feedback should:

6. Provide opportunities to act on (respond to) feedback

Align your feedback to goals/criteria

Provide feedback as action points

Linked assignments so feedback can be used

Reward actual use of feedback in a new task (Gunn,

2010)

Get students to respond to teacher feedback – say what

it means

Get groups to discuss feedback and create action plan

Get students to say how used feedback when submit

next assignment [proforma]

Ensures feedback is processed and leads to knowledge building. Key

principle if your goal is to enhance NSS results](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/principlesasdiscourse-ablueprintfortransformationalchangeinassessment-150930131207-lva1-app6892/85/Principles-as-discourse-A-Blueprint-for-transformational-change-in-assessment-15-320.jpg)

![Further resources

Nicol, D (2009) Transforming assessment and feedback: enhancing

integration and empowerment in the first year. Scottish

Enhancement themes publication http://tinyurl.com/ca7dygx

Nicol, D. (2012) Transformational change in teaching and learning:

recasting the educational discourse, Evaluation of the Viewpoints

project at the University of Ulster. Funded by JISC UK. July 22nd

[also provides a detailed description of workshop with variations]

http://www.reap.ac.uk/TheoryPractice/Principles.aspx

Viewpoints Resources: provides presentation template, workshop plan,

principles cards, timeline etc that can be downloaded.

http://wiki.ulster.ac.uk/display/VPR/Home

Grant and Marshak (2011) Towards a discourse centred understanding of

organisational change, Journal of Applied Behavioural Science, 47(2),

204-235

See also other resources on REAP website at www.reap.ac.uk especially

page at www.reap.ac.uk/TheoryPractice/Principles.aspx](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/principlesasdiscourse-ablueprintfortransformationalchangeinassessment-150930131207-lva1-app6892/85/Principles-as-discourse-A-Blueprint-for-transformational-change-in-assessment-49-320.jpg)

![References

Nicol, D (2012) Transformational change in teaching and learning: recasting

the educational discourse, Evaluation of the Viewpoints project at the

University of Ulster. Funded by JISC UK. July 22nd [This document shows how

the principles developed in Nicol, 2009 were turned into a toolkit and used to

spread a new discourse across a whole HE institution.]

Nicol and Draper (2009) A blueprint for transformational organisational change

in higher education: REAP as a case study available at:

http://www.reap.ac.uk/TheoryPractice/Principles.aspx

Nicol, D. (2009) Transforming assessment and feedback: enhancing integration

and empowerment in the first year. Published by the Quality Assurance

Agency for Higher Education. [This document provides a list of 12 principles,

the research rationale for each, an explanation , some examples of how they

could be implemented in different disciplinary contexts]

Nicol, D, (2009), Assessment for Learner Self-regulation: Enhancing

achievement in the first year using learning technologies, Assessment and

Evaluation in Higher Education, 34(3),335-352

Nicol, D, J. & Macfarlane-Dick (2006), Formative assessment and self-

regulated learning: A model and seven principles of good feedback practice,

Studies in Higher Education, 31(2), 199-218.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/principlesasdiscourse-ablueprintfortransformationalchangeinassessment-150930131207-lva1-app6892/85/Principles-as-discourse-A-Blueprint-for-transformational-change-in-assessment-50-320.jpg)