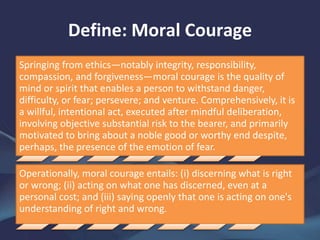

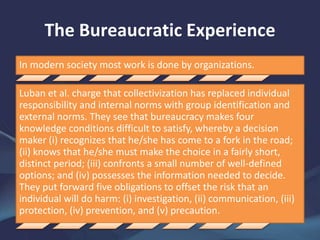

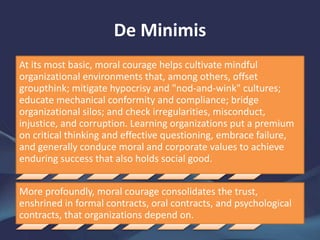

The document discusses the concept of moral courage, defining it as the ability to act rightly despite opposition and personal risk, emphasizing its importance in modern organizational environments. It critiques bureaucracy for diminishing individual responsibility and highlights the necessity for organizations to foster critical thinking and uphold ethical standards in the face of moral complexity. The growing globalization and competition require organizations to adapt by embracing values of honesty and authenticity to navigate ethical challenges successfully.