This document summarizes a research study that examined self-determination in post-secondary students with learning disabilities based on whether they were identified as having an LD in primary/secondary school or as an adult. The study found no statistically significant differences in self-determination, as measured by a self-determination scale, between the two groups of students. The discussion considers limitations of the study related to measurement, sample size, and sampling biases. Implications are discussed for further examining the relationship between time of LD identification and self-determination with more reliable measures and larger sample sizes.

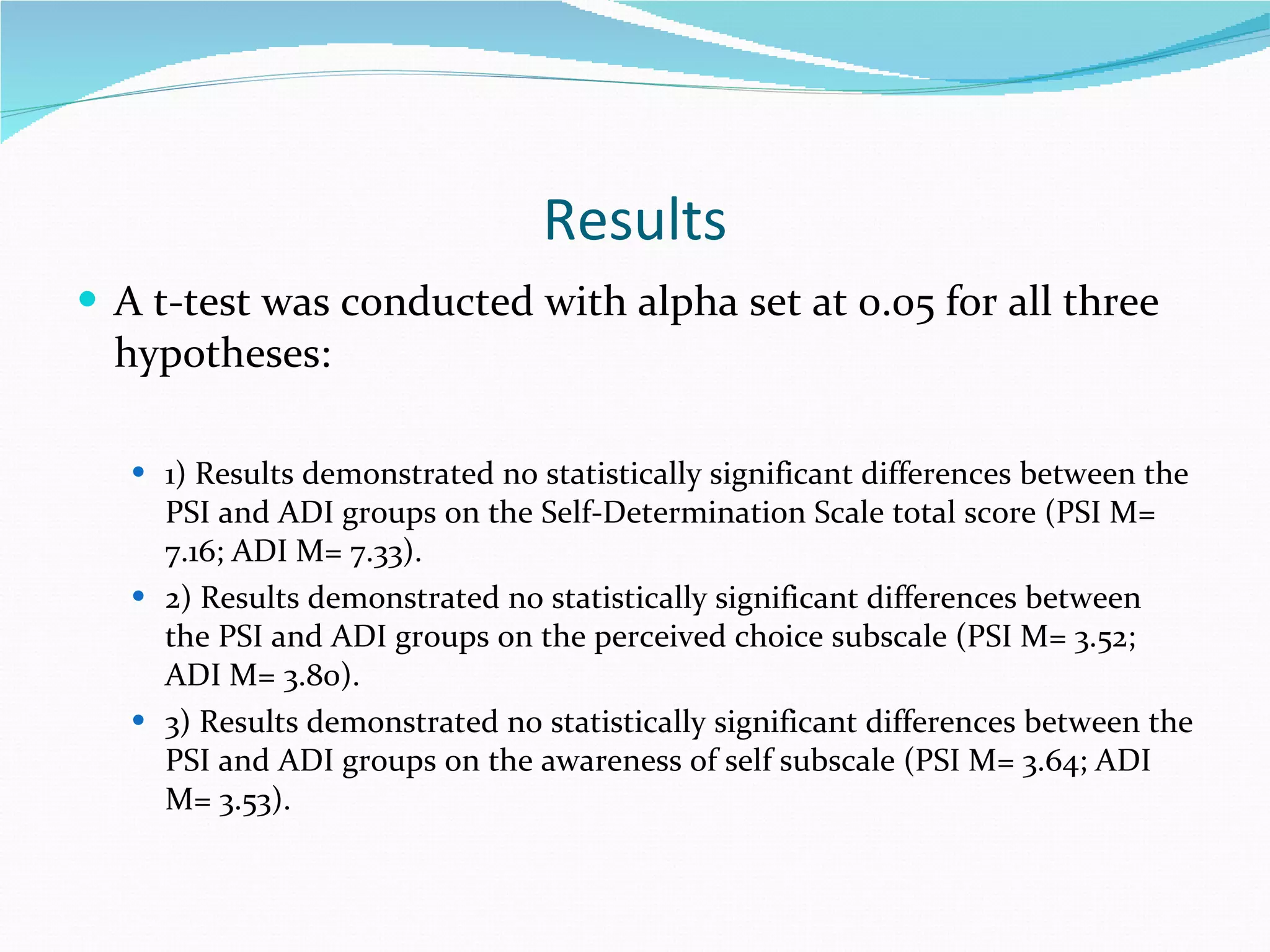

![Results Continued An independent sample t-test was conducted to compare the Self-Determination Scale total score (SDSTS), perceived choice (PC) and awareness of self (AS) with PSI and ADI participants: SDSTS for PSI and ADI participants: There was no statistically significant differences in scores for the PSI (M = 7.16, SD = 1.53) and ADI (M = 7.33, SD = 1.96); [t (38) = -.28, p = .78]. PC scores for PSI and ADI participants: There was no statistically significant differences in scores for the PSI (M = 17.59, SD = 4.73) and ADI (M = 19, SD = 4.56); [t (38) = -.852, p = .40]. AS scores for PSI and ADI participants: There was no statistically significant differences in scores for the PSI (M = 18.21, SD = 4.52) and ADI (M = 17.64, SD = 6.07); [t (38) = .324, p= .75).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/powerpointpresentationmathesisapril172008972003doc-101203163040-phpapp01/75/Powerpoint-presentation-M-A-Thesis-Defence-12-2048.jpg)