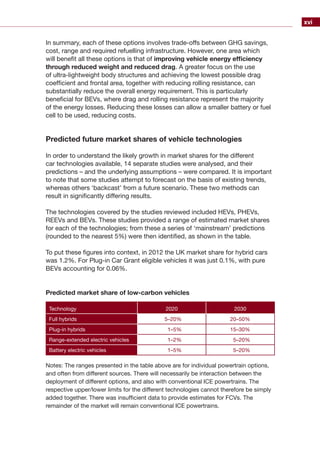

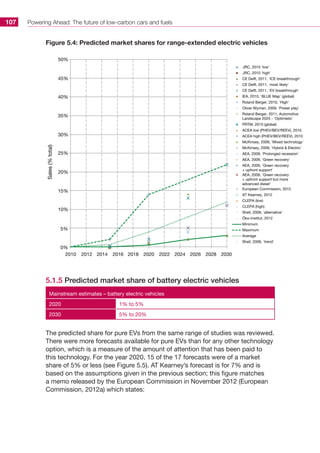

This document provides a summary of the key findings from a report on the future of low-carbon cars and fuels. It finds that conventional petrol and diesel cars will remain dominant until at least 2030, accounting for around 60% of new vehicles. Electric vehicles such as plug-in hybrids are predicted to reach between 5-15% of new car sales by 2020 and 20-50% by 2030. Significant improvements in battery technology are still needed to increase the mass-market potential of electric vehicles. The future role of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles remains uncertain due to high costs and need for clean hydrogen infrastructure. A variety of low-carbon vehicle technologies and fuels will be needed to meet emissions reduction targets.

![Powering Ahead: The future of low-carbon cars and fuels3

(IPCC). Its Fourth Assessment Report, published in 2007, concluded that

“warming of the climate system is unequivocal” and stated that:

“most of the observed increase in global average temperatures

since the mid-20th

century is very likely due to the observed

increase in anthropogenic [caused by human activity] GHG

concentrations” (IPCC, 2007).

It should be noted that despite the widely reported criticism of the report and

the discovery of some minor errors, these conclusions still stand.

Scientific studies since 2007 indicate that the situation appears to be

worsening. In May 2009, ahead of the UNFCCC (United Nations Framework

Convention on Climate Change) negotiations at Copenhagen, a joint statement

from science academics stated that:

“climate change is happening even faster than previously

estimated; global CO2

emissions since 2000 have been higher

than even the highest predictions, Arctic sea ice has been melting

at rates much faster than predicted, and the rise in the sea level

has become more rapid” (G8+5 Academies, 2009).

The IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report will review the more recent scientific

evidence for climate change and draw conclusions based on this. It is due for

finalisation in 2014.

1.2.2 UK policy on climate change

The King Review of low-carbon cars was published the year after Sir Nicholas

Stern’s influential report on the economics of climate change (HM Treasury,

2006). The Stern Review recommended that strong, early action should be

taken to address climate change.

In 2008, the UK became the first country in the world to introduce a law

committing the government to cut GHG emissions. The Climate Change Act

2008 requires an 80% reduction by 2050 relative to a baseline of 1990.

The Department of Energy Climate Change (DECC) reports on UK GHG

emissions. Data for 2011 shows transport to be responsible for 21% of

these emissions, with cars accounting for 55% of that share (Figure 1.1). The

dominant GHG is carbon dioxide (CO2

), and road transport accounts for 24%

of the UK’s total CO2

emissions (NAEI, 2013).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/poweringahead-kayetal-apr2013-130422084840-phpapp02/85/Powering-Ahead-24-320.jpg)

![The Policy Context 12

European transport and fuel policy

The key policy document for transport in Europe is the 2011 Transport White

Paper, which has the aim of “growing transport and supporting mobility while

reaching the 60% emission reduction target [by 2050]” (European Commission,

2011f). This includes objectives of:

• halving the use of ‘conventionally fuelled’ cars in urban transport by 2030

and phasing them out in cities by 2050;

• halving road casualties by 2020 and moving close to zero casualties by

2050;

• reducing oil dependency;

• improving air quality in cities.

The White Paper states:

“The race for sustainable mobility is a global one. Delayed action

and timid introduction of new technologies could condemn the EU

transport industry to irreversible decline. The EU’s transport sector

faces growing competition in fast developing world transport

markets” (European Commission, 2011f: 5).

It goes on to say:

“The synergies with other sustainability objectives such as the

reduction of oil dependence, the competitiveness of Europe’s

automotive industry as well as health benefits, especially improved

air quality in cities, make a compelling case for the EU to step up

its efforts to accelerate the development and early deployment of

clean vehicles” (ibid.).

The European Commission’s strategy for the automotive sector is informed and

guided by a number of bodies, including:

2.2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/poweringahead-kayetal-apr2013-130422084840-phpapp02/85/Powering-Ahead-33-320.jpg)

![Predicted Market Shares of Future Technologies and Fuels 112

The study (European Commission, 2012a: 9) concludes that:

“The emerging [fuel cell vehicle] market (2010–20) requires close value

chain synchronisation and external stimulus in order to overcome the

first-mover risk of building hydrogen retail infrastructure. While the

initial investment is relatively low, the risk is high and therefore greatly

reduced if many companies invest, coordinated by governments

and supported by dedicated legislation and funding. With the

market established, subsequent investment (2020–30) will present

a significantly reduced risk and by 2030 any potentially remaining

economic gap is expected to be directly passed on to the consumer.”

In August 2012, a review of the current status for fuel cell deployment in LDVs

found that FCVs should be seen as complementary to BEVs and PHEVs

(Fuel Cell Today, 2012). It states that BEVs are best realised as smaller cars in

applications that require a continuous range of less than 125 miles, and that

given the limited range of BEVS, FCVs offer the only zero-emissions option for

larger cars travelling longer distances.

Predicted future mix of fuels

The mix of fuels which will power our cars in the future will of course be

determined by the mix of powertrain technologies in use, with the one

exception being the use of biofuels, which can be a direct replacement for

liquid fossil fuels in ICEs. The use of food crop-based biofuels is now being

limited as a result of concerns about the limited GHG reductions achieved,

and wider environmental and social issues (as described in Box 2.1). However,

next-generation advanced biofuels are being developed which address these

issues and can provide high-quality direct replacements for fossil fuels.

As section 5.1 has shown, there are wide variations in the predictions for the

speed with which electrification of powertrains will take place. In this section,

four different scenarios are examined from two different sources:

1. IEA’s baseline and BLUE Map global scenarios for 2050;

2. Ricardo-AEA’s proprietary modelling of ‘business as usual’ and ‘low

biofuel’ scenarios for Europe to 2050.

5.2.1 Future mix of fuels for IEA baseline and BLUE Map

scenarios

IEA’s BLUE Map scenario backcasts from the IPCC targets for a 50% reduction

of energy-related CO2

emissions by 2050 on 2005 levels. Transport is expected

to contribute to this overall reduction by cutting CO2

emissions levels in 2050

to 30% below 2005 levels.

5.2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/poweringahead-kayetal-apr2013-130422084840-phpapp02/85/Powering-Ahead-133-320.jpg)

![References 142

European Commission Enterprise and Industry, Automotive sector website.

Retrieved 21 January 2013 from http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/sectors/

automotive/files/com-2012-636_en.pdf.

European Environment Agency (2012). The contribution of transport to

air quality – TERM 2012: Transport indicators tracking progress towards

environmental targets in Europe, page 37. Retrieved 18 March 2013 from www.

eea.europa.eu/publications/transport-and-air-quality-term-2012.

FEV (2011). In-market Application of Start-Stop Systems in European Market:

Final Report. Retrieved 5 February 2013 from www.theicct.org/sites/default/

files/FEV_LDV%20EU%20Technology%20Cost%20Analysis_StartStop%20

Overview.pdf.

Ford (2011). Streamlined all-new Ford Focus significantly reduces aerodynamic

drag, adding fuel efficiency. Retrieved 5 February 2013 from http://media.ford.

com/article_display.cfm?article_id=33939.

Ford (2012). UK-developed high-tech Ford 1.0-litre EcoBoost engine launched

by Mulally. Retrieved 5 February 2013 from www.ford.co.uk/FordFleet/

NewsAndReviews/FordForBusiness/2012/January/Ecoboost-Engine.

François-Feuerstein, I. (2012). PSA suspend ses achats de voitures

électriques auprès de Mitsubishi [PSA suspends its purchases of electric cars

at Mitsubishi]. LesEchos. Retrieved 5 February 2013 from http://archives.

lesechos.fr/archives/2012/lesechos.fr/08/07/0202207988420.htm.

Frost, L. (2010). Peugeot Citroen Bets on Vehicle-Lease Programs to Power

Electric-Car Sales. Bloomberg. Retrieved 5 February 2013 from www.

bloomberg.com/news/2010-09-06/peugeot-citroen-plans-to-boost-electric-

car-demand-with-leasing-programs.html.

Frost Sullivan (2010). Sustainable and Innovative Personal Transport

Solutions – Strategic Analysis of Carsharing Market in Europe.

Retrieved 25 February 2013 from www.frost.com/sublib/display-report.

do?id=M4FA-01-00-00-00.

Fuel Cell Today (2012). Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles: The Road Ahead. Retrieved

14 March 2013 from www.fuelcelltoday.com/media/1711108/fuel_cell_electric_

vehicles_-_the_road_ahead_v2.pdf.

G8+5 Academies (2009). G8+5 Academies’ joint statement: Climate change

and the transformation of energy technologies for a low carbon future.

Retrieved 17 January 2013 from www.nationalacademies.org/includes/

G8+5energy-climate09.pdf.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/poweringahead-kayetal-apr2013-130422084840-phpapp02/85/Powering-Ahead-163-320.jpg)