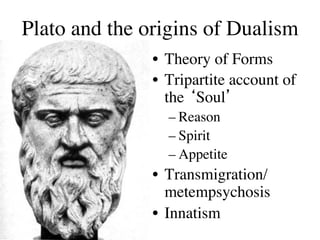

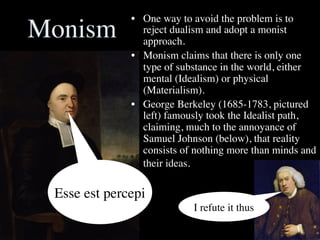

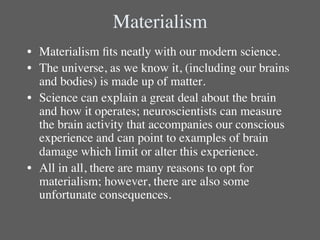

The document discusses the philosophy of mind, primarily focusing on the mind-body problem, which examines the relationship between the mind and body and presents the debates between materialism/physicalism and dualism. It highlights historical perspectives, notably those of Plato and Descartes, while critiquing materialism's challenges, such as the problem of free will and the puzzle of consciousness. Additionally, it introduces concepts like the Turing test, personal identity, and various philosophical thought experiments to illustrate the complexities surrounding consciousness and mental states.

![Problems with Materialism

• The Problem of Free Will

– If we are just complex material machines (physical objects in a

physical universe) then the laws of physics - including the law of

causality - apply to us as much as anything else (Determinism).

This entails that human free will is just an illusion. [We will be

covering this topic in more depth later.]

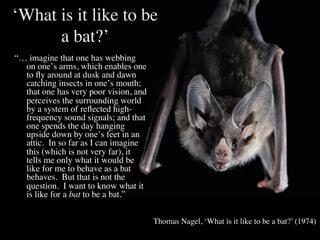

• The Puzzle of Consciousness

– Mental states are unique in terms of their intentionality

(‘aboutness’) and subjectivity. (How) can the world of conscious

experience be explained in terms of the objective physical world?

– The subjective quality of our mental existence has prompted a

great many arguments from contemporary philosophers unhappy

with physicalists’ attempts to reduce the mental world to that of the

physical (reductionism).

– The problem, they state is that no reductive/ physicalist account of

the mind can explain ‘qualia’ (the what-it-is-like-to-have-ness of

our mental states).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/philosophy03-121007063028-phpapp01/85/Philosophy03-8-320.jpg)

![Mary’s Room

“Mary is a brilliant scientist

who is, for whatever reason,

forced to investigate the world

from a black and white room

via a black and white

television monitor. She

specializes in the

neurophysiology of vision and

acquires, let us suppose, all the

physical information there is

to obtain about what goes on

when we see ripe tomatoes, or

the sky, and use terms like

‘red’, ‘blue’, and so on.

She discovers, for example, just which wavelength combinations from the sky stimulate the

retina, and exactly how this produces via the central nervous system the contraction of the vocal

cords and expulsion of air from the lungs that results in the uttering of the sentence ‘The sky is

blue’. [...] What will happen when Mary is released from her black and white room or is given a

color television monitor? Will she learn anything or not?”

Frank Jackson, ‘Epiphenomenal Qualia’ (1982) or ‘What Mary didn’t know’ (1986)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/philosophy03-121007063028-phpapp01/85/Philosophy03-10-320.jpg)