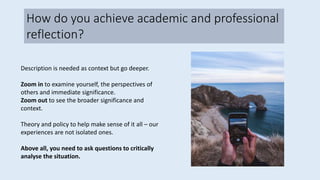

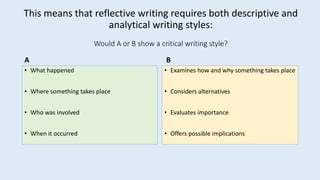

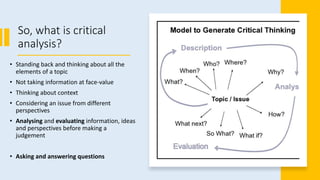

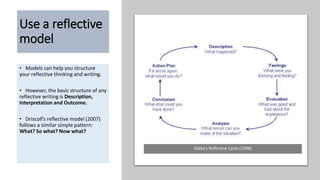

This document provides guidance on reflective writing for postgraduate students. It explains that reflective writing involves both describing experiences and critically analyzing them using relevant theories and frameworks. Examples of student reflections are provided to demonstrate strong reflective writing. The document emphasizes that reflective writing requires interpreting experiences at both a deeper personal level and a broader contextual level. It also stresses the importance of asking critical questions to analyze situations from different perspectives rather than taking information at face value. Various reflective models are presented to help structure reflective thinking and writing, including Driscoll's "What? So what? Now what?" approach and Gibbs' reflective cycle. The document concludes by outlining linguistic features commonly used in reflective writing, such as using first person and action verbs.