Peter Zumthor is a highly regarded Swiss architect known for his minimalist and experiential architectural style, winning the Pritzker Prize in 2009. His notable works include the Therme Vals, Kunsthaus Bregenz, and the Bruder Klaus Field Chapel, which emphasize materiality and sensory experience over aesthetic concerns. Zumthor’s philosophy, influenced by phenomenology, focuses on the 'presence' of buildings, which he believes must be experienced firsthand to be understood.

![Peter Zumthor: Seven Personal Observations on Presence In

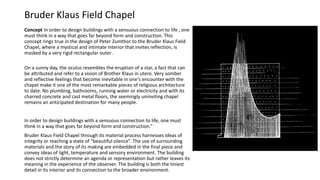

Architecture

1: Spring 1951

“[It] was a beautiful day. There was no school. It must have

been early spring - I could smell it [...] I remember myself

running as a boy, and I had this lightness and elegance

which I don’t have anymore.”

Zumthor, born the son of a cabinet-maker in 1943, began by recounting a seminal

experience from his childhood: “I didn’t know it then, but as an old man now,

looking back, I realize this was my first experience of presence.” As he defines it:

“Presence is like a gap in the flow of history, where all of [a] sudden it is not past

and not future.”

How can presence be translated or achieved in architecture? This question is a key

motive in Zumthor’s atelier in the Swiss region of Graubünden. Founded in 1979,

his home-based studio is located in the valley of the Rhein, where many of his

seminal works - ranging from small-scale projects, such as home renovations and

village chapels, to large-scale, monumental museums - have been built. Zumthor

purposefully maintains his Atelier in this humble, remote location in order to

ensure his experience of “presence”: “Every once in a while, I get this feeling of

presence. Sometimes in me, but definitely in the mountains. If I look at these

rocks, those stones, I get a feeling of presence, of space, of material.”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/peterzumthor-200415062506/85/Peter-zumthor-6-320.jpg)

![3. Constructing presence in architecture: First attempt - Pure Construction

Zumthor recalls a 1993 competition to design a museum and documentation

center of the Holocaust, The Topography of Terror Museum, located in the former

Gestapo headquarters in Berlin. He describes the difficulties of creating

architecture in such a historically charged site: “All that had happened

there came into my mind. [It was] a center for destruction [… ] I

can not do anything here. [...] How can you find the form?”

Rather than making a bold, controversial statement, as many of his fellow

architects would do, Zumthor instead decides to translate his inability to react to

the site by withholding architectural metaphors and symbolism. He decides to

design a building with “no meaning, no comment” by inventing a building of pure

construction.

Although Zumthor’s design was chosen as the winner of the competition,

construction was halted in 1994 and the building’s bare, concrete core stood

vacant for a decade. When funding was regained, political shifts called for a new

architectural competition, which led to the destruction of Zumthor’s unfinished

museum.Though the building was demolished, the idea for a construction-

inspired memorial site was not.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/peterzumthor-200415062506/85/Peter-zumthor-8-320.jpg)

![5. Constructing presence in architecture: Third attempt - Form

follows anything

Or: The body of architecture

“For me, architecture is not primarily about form, not at

all.”

“Form FollowsAnything” was a title of a symposium

Zumthor attended some twenty years ago. “I think that’s a

great title. Architecture can be used to do anything.The

form is open.”

As Zumthor presents the next slide, the audience gasps - it is an

interior shot of what is perhaps his most celebrated and praised

project to date, theTherme Vals

“We actually never talk about form in the office.

we talk about construction, we can talk about

science, and we talk about feelings [...] From the

beginning the materials are there, right next to

the desk […] when we put materials together, a

reaction starts [...] this is about materials, this is

about creating an atmosphere, and this is about

creating architecture.”

In the case of theVals, the materials used were a mixed of locally

quarried stones along with Italian stones: “trust your materials.”

Following the prolonged seven years design process of the Vals, he

could gladly say: “I found out that stone and water have a love

relationship.”

Thermae Vals](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/peterzumthor-200415062506/85/Peter-zumthor-11-320.jpg)

![6. Constructing presence in architecture: Fourth attempt - The house

without a form

While teaching at Harvard, Zumthor tasked his

students with designing “The house without a

form,” for someone whom they share a close,

emotional relationship with. They were to present

the site with no plans, sections or models. The

objective was to inspire a new sort of space,

described by sounds, smells and verbal description:

“When I look at this kind of house

without a form, what interests me the

most is emotional space. If a space

doesn’t get to me, then I am not

interested [...] I want to create emotional

spaces which get to you.”

Bruder Klaus Field chapel](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/peterzumthor-200415062506/85/Peter-zumthor-12-320.jpg)