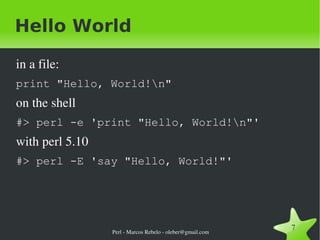

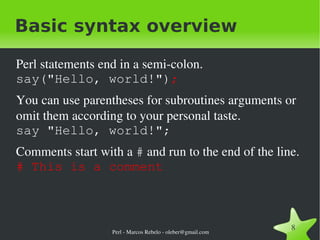

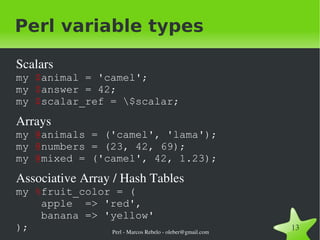

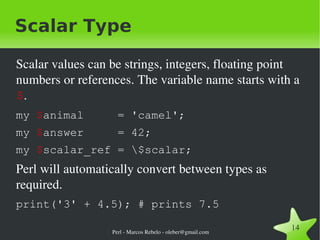

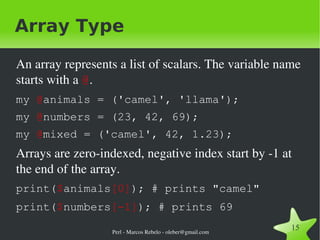

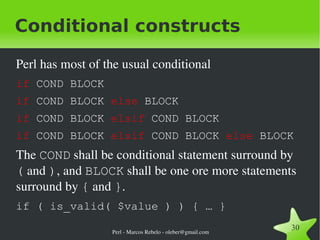

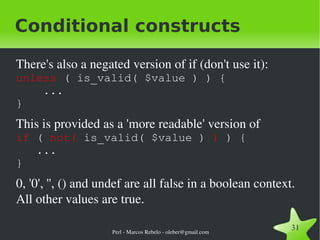

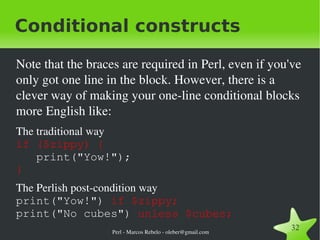

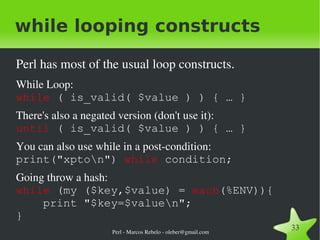

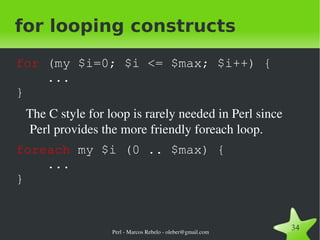

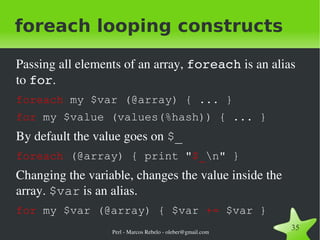

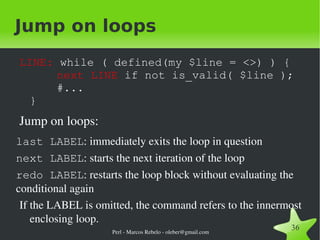

Perl is a general-purpose programming language created by Larry Wall in 1987. It supports both procedural and object-oriented programming. Perl is useful for tasks like web development, system administration, text processing and more due to its powerful built-in support for text processing and large collection of third-party modules. Basic Perl syntax includes variables starting with $, @, and % for scalars, arrays, and hashes respectively. Conditional and looping constructs like if/else, while, and for are also supported.

![my @ mixed = ('camel', 42, 1.23); Arrays are zero-indexed, negative index start by -1 at the end of the array. print( $ animals [0] ); # prints "camel"](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/perlintroduction-090914015218-phpapp01/85/Perl-Introduction-45-320.jpg)

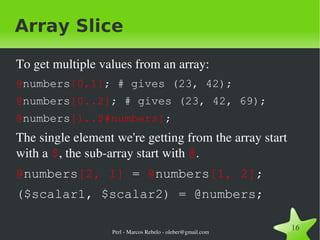

![print( $ numbers [-1] ); # prints 69](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/perlintroduction-090914015218-phpapp01/85/Perl-Introduction-46-320.jpg)

![Array Slice To get multiple values from an array: @ numbers [0,1] ; # gives (23, 42);](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/perlintroduction-090914015218-phpapp01/85/Perl-Introduction-47-320.jpg)

![@ numbers [0..2] ; # gives (23, 42, 69);](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/perlintroduction-090914015218-phpapp01/85/Perl-Introduction-48-320.jpg)

![@ numbers [1..$#numbers] ; The single element we're getting from the array start with a $ , the sub-array start with @ .](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/perlintroduction-090914015218-phpapp01/85/Perl-Introduction-49-320.jpg)

![@ numbers [2, 1] = @ numbers [1, 2] ;](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/perlintroduction-090914015218-phpapp01/85/Perl-Introduction-50-320.jpg)

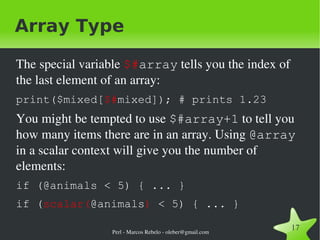

![Array Type The special variable $# array tells you the index of the last element of an array: print($mixed[ $# mixed]); # prints 1.23 You might be tempted to use $#array+1 to tell you how many items there are in an array. Using @array in a scalar context will give you the number of elements: if (@animals < 5) { ... }](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/perlintroduction-090914015218-phpapp01/85/Perl-Introduction-52-320.jpg)

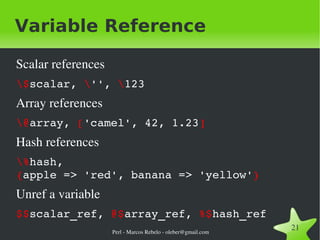

![Variable Reference Scalar references \$ scalar, \ '' , \ 123 Array references \@ array, [ 'camel', 42, 1.23 ] Hash references \% hash, { apple => 'red', banana => 'yellow' } Unref a variable $$ scalar_ref, @$ array_ref, %$ hash_ref](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/perlintroduction-090914015218-phpapp01/85/Perl-Introduction-59-320.jpg)

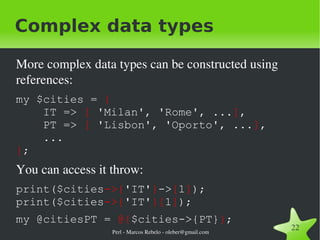

![Complex data types More complex data types can be constructed using references: my $cities = { IT => [ 'Milan', 'Rome', ... ] , PT => [ 'Lisbon', 'Oporto', ... ] , ... } ; You can access it throw: print($cities ->{ ' IT' } -> [ 1 ] ); print($cities ->{ ' IT' }[ 1 ] );](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/perlintroduction-090914015218-phpapp01/85/Perl-Introduction-60-320.jpg)

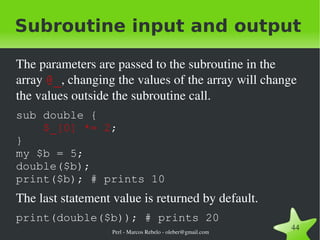

![Subroutine input and output The parameters are passed to the subroutine in the array @_ , changing the values of the array will change the values outside the subroutine call. sub double { $_[0] *= 2 ; } my $b = 5; double($b); print($b); # prints 10 The last statement value is returned by default. print(double($b)); # prints 20](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/perlintroduction-090914015218-phpapp01/85/Perl-Introduction-114-320.jpg)

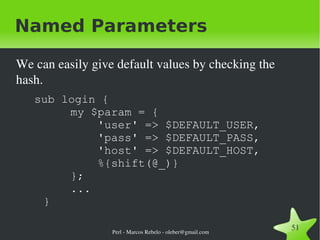

![Named Parameters We can also write the subroutine so that it accepts both named parameters and a simple list. sub login { my $param; if ( ref($_[0]) eq 'HASH' ) { $param = $_[0]; } else { @{$param}{qw(user pass host)}=@_; } ... } login('Login', 'Pass'); login({user => 'Login', pass => 'Pass'});](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/perlintroduction-090914015218-phpapp01/85/Perl-Introduction-122-320.jpg)