The document discusses several pelagic predators including sea turtles, albatrosses, sea birds, marine mammals, and elephant seals. It provides details on the life cycles and behaviors of these species, including information on their ranges, habitats, feeding strategies, and population recoveries after historic hunting. Links are included to additional resources on the biology and ecology of these pelagic predators.

![Evolution of Marine Mammals

“Abstract: The fossil record demonstrates that mammals re‐entered

the marine realm on at least seven separate occasions. Five of these

clades are still extant, whereas two are extinct. This review presents a

brief introduction to the phylogeny of each group of marine mammals,

based on the latest studies using both morphological and molecular

data. Evolutionary highlights are presented, focusing on changes

affecting the sensory systems, locomotion, breathing, feeding, and

reproduction in Cetacea, Sirenia, Desmostylia, and Pinnipedia.

Aquatic adaptations are specifically cited, supported by data from

morphological and geochemical studies. ”

-- M.D. Uhen “Evolution of marine mammals: Back to the sea after 300 million years,”

Anatomical Record

Volume 290, Issue 6, [Special Issue: Anatomical Adaptations of Aquatic Mammals]

June 2007 Pages 514-522](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pelagicenvironmentandecology3copy-210430035225/85/Pelagic-Environments-and-Ecology-3-copy-24-320.jpg)

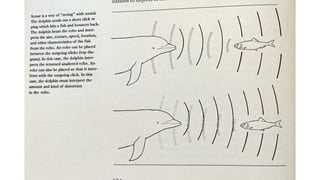

![A behavioural framework for the evolution of feeding in predatory aquatic mammals, Volume: 284, Issue: 1850, DOI: (10.1098/rspb.2016.2750)

“Within our new framework, semi-aquatic feeding describes any feeding events where some

behaviours occur underwater (e.g. ram feeding or snapping during prey capture), while others

occur in air at the surface, either while floating or treading water, or while hauled out on land (e.g.

prey manipulation and processing). Both otters and pinnipeds use semi-aquatic feeding when

consuming large prey, which is typically captured underwater before being processed at the surface

[26,37]. Water ingested along with prey can generally be drained from the oral cavity while the

head is held clear of the water.

“In contrast to semi-aquatic feeding, aquatic raptorial feeding describes feeding events where all

components of the feeding cycle occur underwater. Here, snapping and ram feeding are typically

used for prey capture, although suction may facilitate the process by drawing prey within range of

the teeth prior to biting [17]. Following initial capture, intraoral suction is used to transport prey to

the back of the oral cavity, with any ingested water being expelled via simple sieving. Aquatic

raptorial feeding is common among pinnipeds and dolphins, both of which tend to capture and

swallow small fish whole. In some cases, however, larger prey is also targeted and may be partly

processed underwater by shaking or tearing [38].

“Suction feeding describes events where prey capture occurs mainly via suction. For this mode of

capture to be effective, targeted prey is typically small enough to be sucked entirely into the oral

cavity, with minimal or no prey processing [37]. Prey can be either immobile (e.g. benthic

invertebrates) or evasive (e.g. squid), with the latter sometimes requiring prolonged chases [48,49].

In cetaceans, specialization towards suction feeding tends to be accompanied by the loss of most or

all of the teeth (e.g. beaked whales) [14]. Following suction, simple sieving is used to retain

individual prey items inside the oral cavity while water is expelled.

“Suction filter feeding is effectively an extension of suction feeding, but, instead of simple sieving,

uses a specialized filter to separate prey from ingested water. This filter consists of either highly

elaborate teeth (in leopard and crabeater seals) [7,43] or baleen (in the grey whale) [34,47], and is

capable of retaining smaller prey than simple sieving, thus enabling suction filter feeders to gather

small prey in bulk. Finally, filtering and bulk feeding are also characteristic of ram filter feeding,

which is arguably the most highly specialized of all aquatic mammal strategies. Ram filter feeding is

only used by baleen-bearing mysticetes, and involves neither suction nor teeth to capture prey.

Instead, prey is ingested via continuous (skim feeding, as seen in right whales) or intermittent

(lunge feeding, as seen in rorquals) ram movements, and then retained in the oral cavity via a

specialized filter while excess water is expelled [5,50].”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pelagicenvironmentandecology3copy-210430035225/85/Pelagic-Environments-and-Ecology-3-copy-29-320.jpg)

![Natural cormorant predation…

“Based on estimated ratios of non- breeders to breeding pairs, the NBE [Narragansett Bay Estuary]population

of the Double-crested Cormorant in the late 1990s was about 11,000 birds, a level where it appears to remain

at present. Estimates of numbers of the Great Cormorant (Phalacrocorax carbo) in the NBE are not available,

but since they primarily migrate through the area in spring and fall and do not breed in NBE, their fish

consumption would be much lower than for the Double-crested Cormorant population.

“About 85% of the Double-crested Cormorants nest in the Sakonnet River, with 34% of the total population

nesting at Little Gould Island in the upper part of the Sakonnet River and 51% nesting around Sakon- net Point

(Figure 2). The majority of the remainder, 13% of the population, nest at Hope Island in the West Passage of

Narragansett Bay. Cormorants fly up to 8–16 km to feed in waters shallower than 8 m. The relatively large

population associated with the Sakonnet River nesting colonies most likely feeds in Mount Hope Bay and the

Sakonnet River, where shallow-water foraging areas are much more extensive than in nearby waters of the

lower East Pas- sage of Narragansett Bay. Thus, predation pressure on fish is likely higher in Mount Hope Bay

and the Sakonnet River than in the East and West Pas- sages of Narragansett Bay.

“Fish consumption rates per day were estimated for adults and their chicks based on bioenergetic modeling,

i.e., by estimating their calorific requirements for metabolism, daily activities, and growth. The amount of fish

consumed annually per cormorant in the population (on average) was estimated accounting for breeding rates,

chicks hatched per nest, chick growth rate and food needs, survival to fledging, and survival from fledging to

fall migration. A full-grown bird consumes about 510 g of fish per day, or 93 kg in the 6 months it resides in

the NBE (April to October). An additional 57 kg per breeding adult is consumed by their young before fall

migration. The total consumption of fish by the Double-crested Cormorant population in the NBE during

April–October was estimated at about 1.2 million kg (2.7 million lb) annually from 1993 to 1997. “

"Estimating Fish Predation by Cormorants in the Narragansett Bay Estuary,"

Deborah P. French, McCay Rowe and Jill J. Rowe.

Rhode Island Naturalist V. 11:2, November 2004.

https://rinhs.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/ri_naturalist_fall04.pdf](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pelagicenvironmentandecology3copy-210430035225/85/Pelagic-Environments-and-Ecology-3-copy-75-320.jpg)