This document discusses peer relationships in childhood development. It covers several key points:

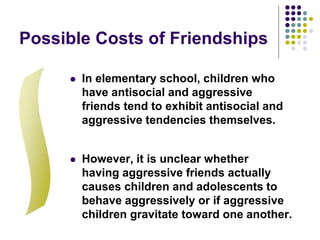

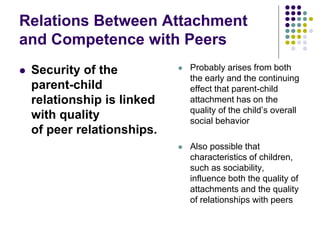

- Peer relationships provide a unique context for cognitive, social, and emotional development through equality, reciprocity, cooperation and intimacy.

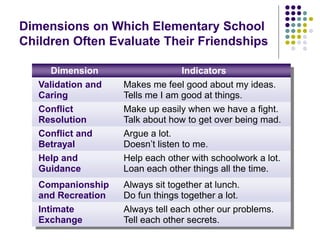

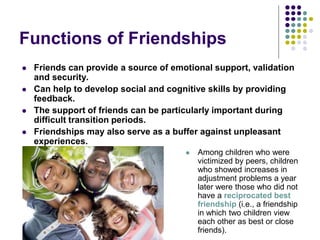

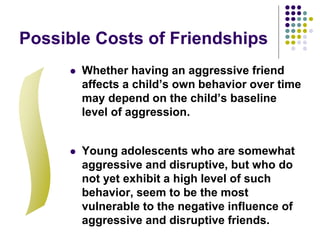

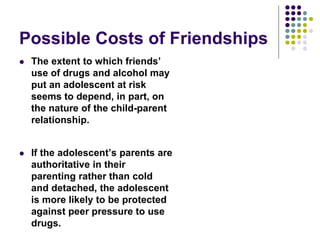

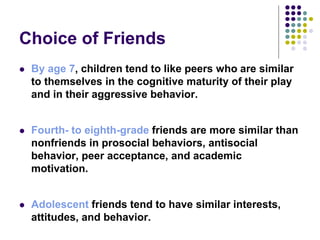

- Friendships become more evident with age and are defined by mutual liking, closeness and loyalty from early childhood through adolescence.

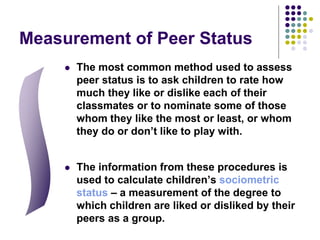

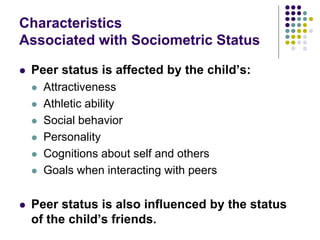

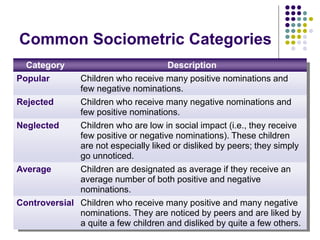

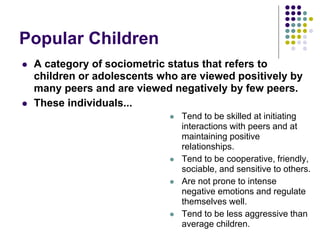

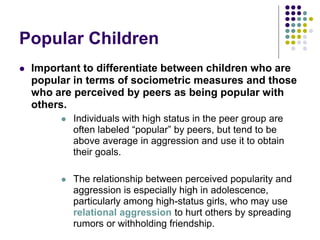

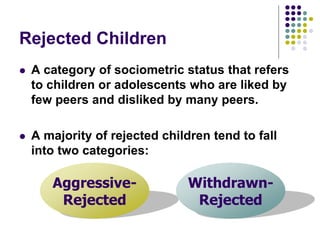

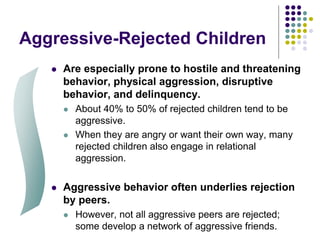

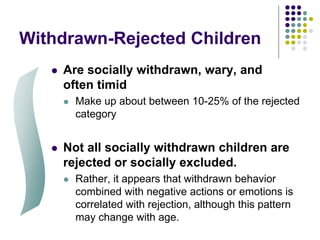

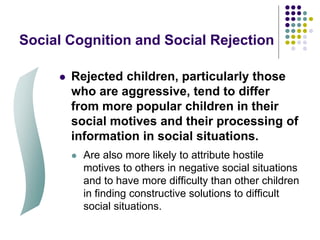

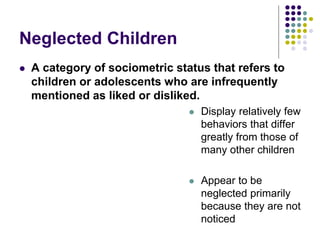

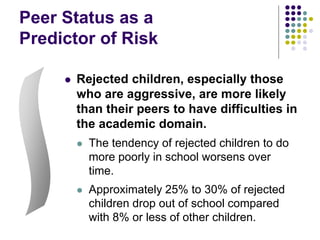

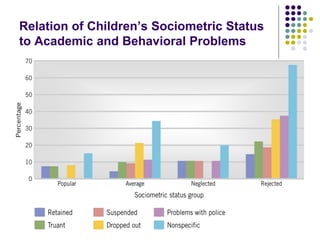

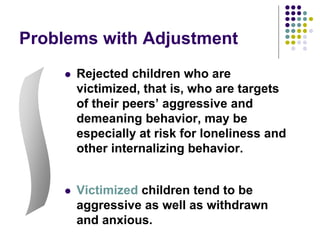

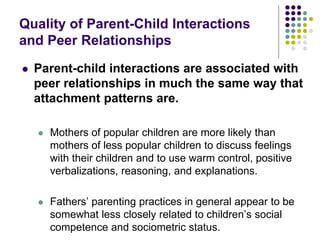

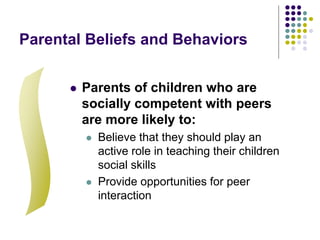

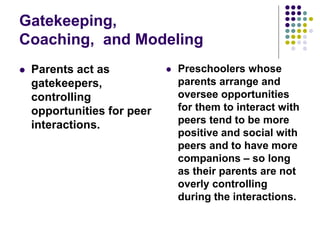

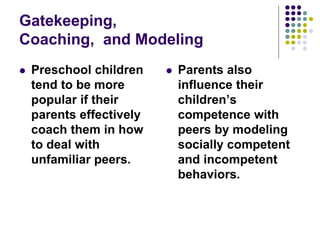

- Peer status and sociometric categories like popular, rejected, neglected and controversial are influenced by attributes like attractiveness, behavior and friend networks.

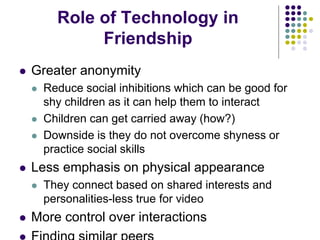

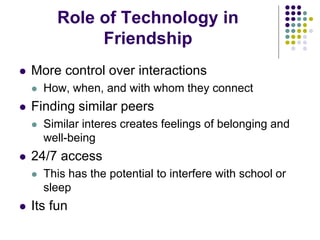

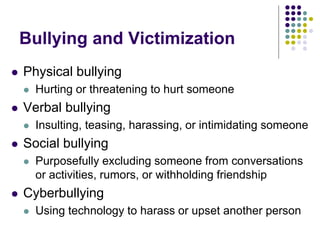

- Technology plays a role in modern friendships by enabling connection based on shared interests while also potentially interfering with in-person social skills and sleep.