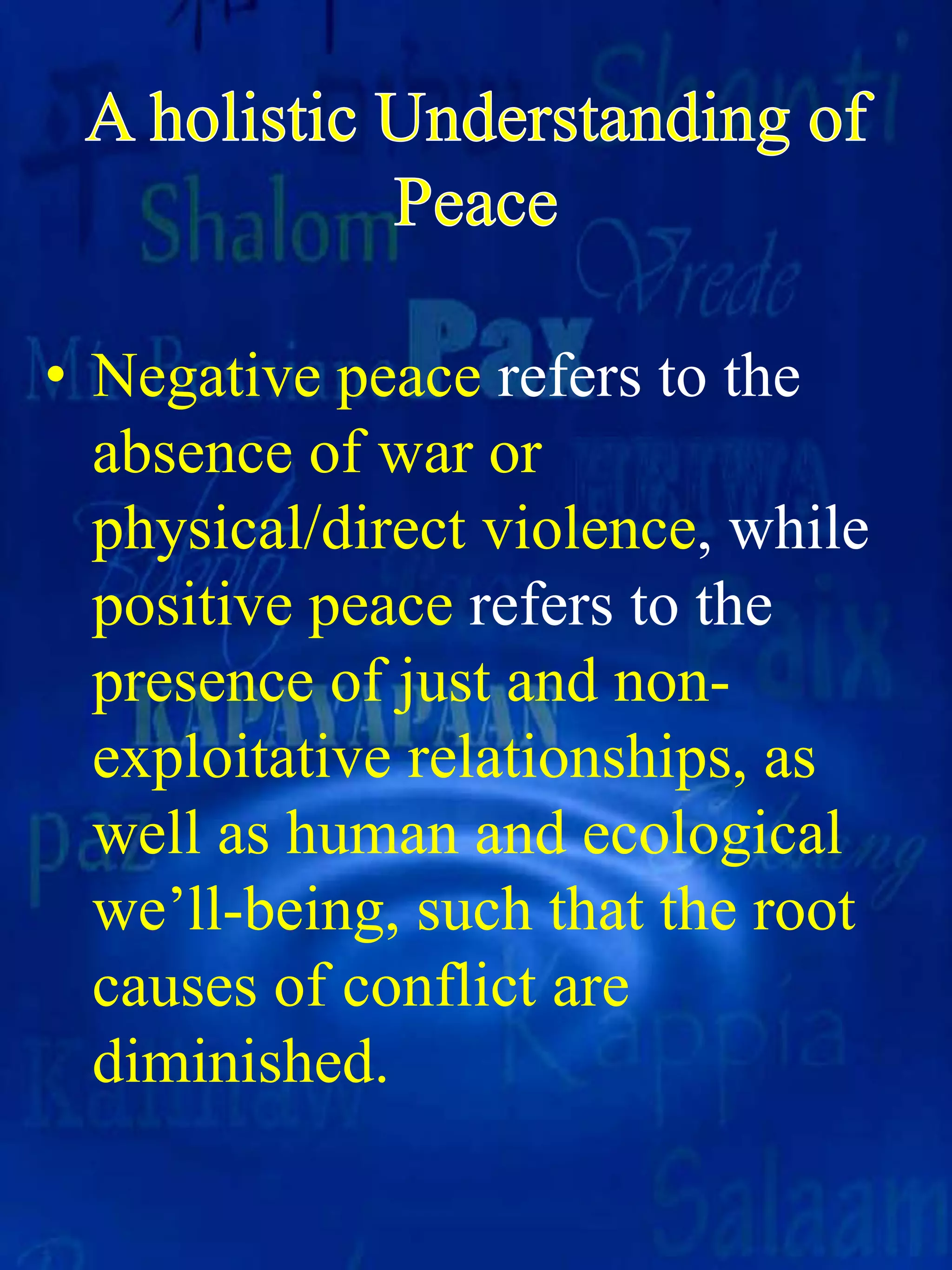

The document discusses the concept and definitions of peace education. It explains that peace education aims to transform thinking by developing understanding of concepts like structural violence and positive peace. The goal is to cultivate knowledge, skills, attitudes and values that can help resolve conflicts nonviolently and create just relationships and social structures. Key aspects of peace education include teaching about the holistic concept of peace, root causes of violence, and alternatives like nonviolence and conflict resolution.