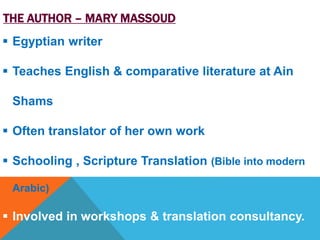

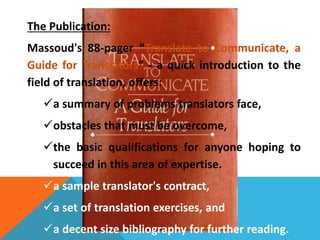

This document provides a summary of Mary Massoud's monograph "Translate to Communicate - A Guide for Translators". The monograph is an 88-page introduction to the field of translation. It covers topics such as problems translators face, qualifications for translators, sample contracts and exercises. It is designed to help both new and experienced translators. The document summarizes each of the 7 sections of the monograph, providing an overview of its key points around topics such as the role of translators, evaluating translation quality, and matching translation projects to skills. It emphasizes the importance of understanding the intended reader and culture when translating.

![i. Introduction:

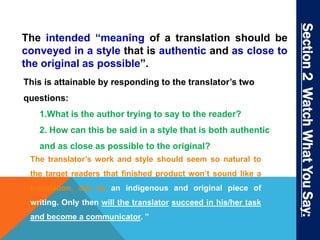

History of translation :

>Septuagint > Arabs >Post-Rosetta Stone Era > “Age of Instant

Translation”.

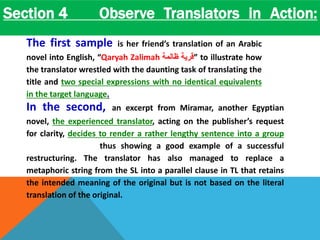

Defines two types of

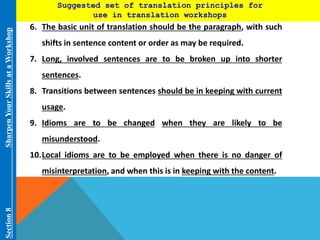

translation:

[1] “Translation Bureaux”

facilitates rendering of SL into TL

in few hours at expense of

quality.

[2] “Sound & Effective Translation” (SET)

Culture sensitive,

Readership awareness

Subtlety of language

Monograph objective: Assist translators to produce translations that

communicate intended message in authentic style.

Specifically designed for new translators and experienced ones with little formal

training.

Concludes with Nainggolan’s quotation referring to the third world countries’

need for good translators, "training of good and productive translators can be a

matter of life and death for the nation."](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/overview-marymassoudstranslatetocommunicate-140918042209-phpapp01/85/Overview-mary-massoud-s-translate-to-communicate-5-320.jpg)

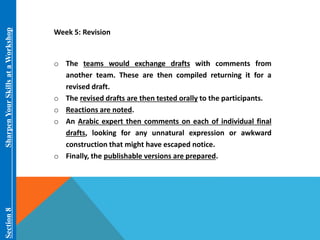

![Choosing the participants

The first step is to choose those who will be trained

at the workshop. Invite experienced translators or

staff members with potential, recruit new talents

[with a notice in the papers, and another to (a)

university (-ies)].

It is recommended to start with a consultation

session during which a brief explanation of basic

principles, procedures, and problems of translation

is given. (These are presented in this book.)

This leads to an Informal Translating Test to assess

which of the participants have potential to become

good translators. These are selected for training at

the workshop.

Section 8 Sharpen Your Skills at aWorkshop](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/overview-marymassoudstranslatetocommunicate-140918042209-phpapp01/85/Overview-mary-massoud-s-translate-to-communicate-42-320.jpg)