This document is the introduction to a master's thesis written in Polish that analyzes the translation of functional texts from the perspective of Skopos theory. The introduction provides background on Skopos theory and its focus on the purpose and function of translation. It also discusses the complexity of translation due to differences in language and culture. The purpose of the thesis is to analyze how Skopos theory concepts can help address culture-specific issues that arise in translating various types of functional texts in practice. The introduction outlines the chapters to follow on Skopos theory, the concept of culture in translation theory, and example studies applying Skopos to resolve culture-specific challenges in domains like manuals, advertising, tourism and legal translation.

![(Nord 1997: 37-38). Each of these categories determine which of the given text type‟s

elements require a greater degree of equivalence in translation.

Reiss describes the resulting categories as follows: informative texts, as the very name

suggests, intend to provide information to their readers as regards “various objects and

phenomena in the real world” (ibid.: 38). This function is also their top priority, placing the

employed language and style as secondary elements. Consequently, when translating

informative texts, the translator must strive to preserve all their referential value while

adjusting the secondary elements to target-culture norms (ibid.).

The second category, expressive texts, are notably different from its predecessor in

that the information theв carrв is “complemented or even overruled bв an aesthetic

component” (ibid.). The aesthetic component is constituted bв the text‟s informational

content as well its style, with both intending to have a particular “aesthetic effect” on the

reader. Reiss claims that when working on such texts, the translator‟s top prioritв is to assure

that their translation will evoke a similar kind of „rhetorical impression‟ on the target reader

as the source text does on the source reader (ibid.).

The last of Reiss‟s categories is the operative text. In this type of text, it is both the

form and content that play secondary roles, whereas its most important feature is the general

“extralinguistic effect that the text is designed to achieve” (ibid.). Operative texts are notably

pragmatic in nature. Their purpose is to perform certain actions, or make their intended

readers respond in a particular way. Consequently, it is necessary for the text to retain such

effects in translation.

Nord criticises Reiss‟s tвpologв as a sвstem that is still confined to the linguisticallв-

oriented notion of equivalence. She claims that in a theory where “the decisive factor in

translation” is “the dominant communicative function of the source text … any particular

text, belonging to one particular text type, would allow for just one way of being translated,

the „equivalent‟ waв” (ibid.: 39). Although Reiss‟s tвpologв recognises the need for applвing

different solutions to different types of texts, it does not allow for a variety of solutions for

one particular text type. As Nord states, functionalism does not deal with replacing certain

elements of the source text with ones that best reflect the given communicative function in the

target culture. What trulв matters is that the translator “be aware of these [communicative]

aspects and take them into consideration in their decisions” (ibid.). In order to resolve this

uncertainty, Nord proposes to redirect the focus of Reiss‟s system from source texts to target

texts.

17](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/scopostheory-141101042822-conversion-gate01/75/Scopos-theory-18-2048.jpg)

![The most important factor [to the functional approach] is the skopos (Greek for aim, purpose,

goal), hence the purpose or function of the translation in the target culture, as specified by the

client (in a translation brief) or the envisaged user-expectations; translation is hence prospective

rather than, as had hitherto been the case, retrospective (Snell-Hornby 2006: 54).

For a certain reason that remains unexplained, however, Snell-Hornby writes about the

prospectiveness of functional translation as alternately based on the demands of the brief and

the target audience. That is not usually the case, for the interests of both these participants

may be sufficiently incongruent to exert contrary demands for one assignment and require the

translator to establish a compromise between them (Nord 2006: 33).

Despite the fact that the presented approach aims to explain the notion of culture in

terms more manageable to Skopos theory, it is still left to operate within a range of various

ideas and issues. It is a fact particularly pertinent to Skopos theory that translation deals with a

broad variety of text types for whom their respective cultural contexts will focus on different

linguistic and extra-linguistic elements in determining their functionality. What is more, in

the current view culture remains a very complex system where precise delimitation is hardly

possible. It is not the case that to each language there is ascribed only one culture which

gathers every phenomenon that conditions its norms and behaviour (Nord 1997: 24). To

elaborate on this, Nord gives the example of cultural similarities found among separate, but

nonetheless spatially close communities such as of those Dutch and Germans who live in

regions close to their common border. Although their languages differ, their value systems

will be similar. Alternatively, the Scots and the English, who constitute distinct communities

of dissimilar origin, will share similar linguistic patterns in some situations while following

their own in others (ibid.: 24). To resolve the question of how to envision the borders of

culture, Nord refers to an altogether different view formulated by the North American

anthropologist Michael Agar. Agar claims that “culture is not something people have; it is

something that fills the spaces between them. And culture is not an exhaustive description of

anything; it focuses on differences, differences that can vary from task to task and group to

group” (ibid.). Agar‟s concept diverges significantlв from the view accepted in this studв in

that he conceives culture purely in terms of differences, as something indescribable as far as

its scope is concerned. However, the point that he makes in his consideration is nonetheless

valid to the issue of delimiting cultures. Culture-specificity may apply to various social levels

and it may also persist across language boundaries. The cultural proficiency of the translator

must in many cases consist not only in the knowledge of what is largely specific to the users

28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/scopostheory-141101042822-conversion-gate01/75/Scopos-theory-29-2048.jpg)

![original, but which would yet in its effects come as close to that whole as the difference in

material allows” (Snell-Hornby 2006: 8).

Schleiermacher categorised the translation of all texts that do not belong to literature

as a “mechanical activitв” (ibid.). This thought may have been motivated by a variety of

factors, such as the amount of fixed-phrase equivalents involved in the translation of legal and

technical texts, etc., which rather suggested literary works as a field for linguistic creativity

both in their production and translation (cf. Schleiermacher in Lefevere 1992: 142-143). A

different reason for this originated from a personal preference that Schleiermacher assumed

with respect to a different theoretical dispute, explained below. Although limited to literature,

Schleiermacher‟s understanding of the translation process relates to the notion of creating the

text anew, accepting other approaches than literal translation, and stressing the effect that the

text is meant to have on the target readership. Overall, it is a step taken in the direction of

target-text-oriented approaches. Another binary concept formulated by Schleiermacher is

taken up for discussion within the field even more frequently:

In my opinion, there are only two [approaches to translation]. Either the translator leaves the

author in peace, as much as possible, and moves the reader towards him; or he leaves the reader in

peace, as much as possible, and moves the author towards him. The two roads are so completely

separate from each other that one or the other must be followed as closely as possible, and that a

highly unreliable result would proceed from any mixture, so that it is to be feared that author and

reader would not meet at all (qtd. by Snell-Hornby 2006: 8).

Today better known as concepts of domestication and foreignisation, further developed by

Lawrence Venuti, Schleiermacher‟s strategies reveal the fact that the readers of the source

text and the target text are culturally heterogeneous groups and, consequently, translation

entails decisions regarding the presentation of thoughts originating from one culture to an

audience existing in a different one. The form of the translation‟s language is determined bв

the movement of authors and readers initiated by the translator, which may take place not

only across linguistic boundaries (if it had, Schleiermacher would have surely determined

paraphrasing as the most efficient mode of translation for any text), but also across space,

time, and organisations of knowledge. Domesticating in his understanding consists in

producing a text whose features adhere to the conventions of the target language and do not

betray its foreignness, whereas foreignising strives to mark the text with this foreign likeness,

keeping its readers aware of the fact that they are dealing with a translation and setting a clear

demarcation between what is native and what is foreign (ibid.: 9). Anthony Pym notes that the

“binarism” characterising Schleiermacher‟s approaches is quite commonplace in the

31](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/scopostheory-141101042822-conversion-gate01/75/Scopos-theory-32-2048.jpg)

![discipline‟s theorв, ranging up to the present times where, although tolerant of “middle

grounds,” various concepts still operate in terms of dichotomies (Pвm 1995Ś 6-7).

Schleiermacher‟s words strictlв underline the need for choosing onlв one of the two

available options, lest the produced translation places the author and the reader at a distance

where proper comprehension is not possible. Even though there appear to be two options

available to the translator, Schleiermacher is far in favour of the foreignising approach. He

advocates the creation of a special language for the purpose of translation, “enriched” bв the

foreignness of the source text‟s setting and maintaining the reader‟s awareness of the target

text‟s distant origin. A language of this kind could be achieved by employing such devices as

archaisms, irregular syntactic patterns, etc. (Snell-Hornby 2006: 9). Pym adds that, although it

is an extensive input on the subject, Schleiermacher‟s writing is not the first to discuss the

subject of domestication and foreignisation. His is a particular view on the matter, grounded

not only in the contemporaneous perception of language but also in the historical context of

the Napoleonic Era and what Pвm calls a “nationalistic opposition,” resulting in his lecture

being “a general attempt to oppose German Romantic aesthetics to the belles infidèles of

French Neoclassicism … He [Schleiermacher] had little contextual reason to look kindly upon

a French translation method” (Pвm 1995Ś 5-6). Additionally, Schleiermacher associated the

foreignising approach exclusively with literary art and academic works due to his belief that

messages conveyed by such texts were bound to highly culture-specific concepts. Their

abundance within them ultimately obliged the translator to employ the foreignising strategy,

as opposed to the terminologв of “everвdaв business texts” that Schleiermacher found easв to

transfer and not in the least challenging in “genuine” translation efforts (Kittel and Polterman

in Baker 1998: 423-424).

A different view regarding the two strategies was upheld by the highly renowned

German writer and thinker Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. During his commemorative address

for Christoph Martin Wieland, a respected translator of Shakespeare into German who died in

1831, Goethe spoke highlв of the translator‟s approach, which consisted in applвing

domestication when facing particularly difficult problems but mostly in resorting to the

method that draws from both strategies, an idea unconditionally advised against by

Schleiermacher. Both Wieland and Goethe were apparently convinced that the

“reconciliation” of both these approaches was highlв possible (Snell-Hornby 2006: 9).

A different scholar worthy of mention as regards the presented concepts, although

preceding both Schleiermacher and Goethe, is the 17th century English writer and translator

32](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/scopostheory-141101042822-conversion-gate01/75/Scopos-theory-33-2048.jpg)

![in relation to the objects that they signify. He underlines in this distinction, however, that

meaning is a linguistic phenomenon derived from signs, and not from the concepts or “things”

that signs denote:

Any representative of a cheese-less culinarв culture will understand the English word “cheese” if

he is aware that in this language it means “food made of pressed curds” and if he has at least a

linguistic acquaintance with “curds.” … Against those who assign meaning (signatum) not to the

sign, but to the thing itself, the simplest and truest argument would be that nobody has ever

smelled or tasted the meaning of “cheese” or of “apple.” (Jakobson [1959] 2000: 113).

Since the meaning of a word is not necessarily expressed by the immediate presence of the

concept to which it is ascribed, it must be formulated by further linguistic material. In terms

of cultural contexts, Jakobson points out precisely that it is not the absence of a concept in a

given culture that impedes its comprehension but the lack of possibility to explain it in terms

available to that culture.

In light of the presented relation, Jakobson enumerates three types of translation:

intralingual, interlingual, and intersemiotic. The first relates to synonymy and paraphrasing

within one language system, which may occur when a speaker attempts to bring out the

meaning of a word, for instance bв stating that “a car is a vehicle” or “wine is the fermented

juice of grapes.” The intersemiotic tвpe is explained as “an interpretation of verbal signs bв

means of signs of nonverbal sвstems” (ibid.: 114). Jakobson put forward observations most

pertinent to the discussion at hand in the context of the interlingual mode of translation, the

kind conducted between languages. Although a greater portion of his discussion is devoted to

the implications that formal differences between languages exert on translation, Jakobson

nonetheless observes certain difficulties of interlingual translation which are caused by extra-linguistic

factors. He states that complete equivalence is not possible when rephrasing texts in

a different language just as it is not possible in the case of synonymy within one language.

The renderings maв instead “serve as adequate interpretations of alien code-units or

messages” (ibid.). To illustrate this problem, he presents the issue of translating between the

English word “cheese” and its seeming Russian equivalent “ɫыɪ.” In the culture of English

language speakers, Jakobson explains, the word “cheese” encompasses anв of the food‟s

known varieties without causing confusion. The Russian-speaking audience, however,

differentiates between cottage cheese (ɬɜоɪоɝ) and anв other pressed varieties (ɫыɪ). Thus, in

standard Russian “ɫыɪ” is in fact the accepted equivalent of “cheese,” but onlв when a

pressed variety free of ferments is in question (ibid.). In a context where this distinction is

relevant, the failure to observe it could indeed result in a mistranslation. Steering somewhat

35](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/scopostheory-141101042822-conversion-gate01/75/Scopos-theory-36-2048.jpg)

![Nida acknowledges that in many respects there exists a relevant connection between language

and culture. It has been stated in the given study that even functionalist concepts themselves

relate back to those elements of the equivalence paradigm which incorporate this idea (cf.

1.1). Is it possible to claim that Skopos theory constituted a turning point in the discipline,

given Nida‟s above statement? What does the linguistic orientation of this paradigm consist

in and on what grounds could Skopos theory consider itself innovative with respect to it? In

order to resolve these issues, let us turn to several considerations on the subject.

Ideas associating translation with culture were at one point absent in the discipline‟s

theoretical input (cf. 1.1). A sharp dividing line drawn between language and culture resulted

in purely linguistically-oriented modes of defining translation. Sugeng Hariyanto presents

several pertinent definitions of translation formulated in the 1960s – 1970s and points out

that it is only the definition proposed by Eugene Nida and Charles Taber from all those listed

that in fact makes anв kind of reference to culture in translationŚ “translating consists of

reproducing in the receptor language the closest natural equivalent of the source language

message, first in terms of meaning and secondlв in terms of stвle” (qtd. in Hariyanto 2009).

Hariвanto claims that this implied reference is found in Nida and Taber‟s concept of the

“closest natural equivalent.” Bв making it the focal point in their definition, he writes, Nida

and Taber maintain that “the equivalent sought after in every effort of translating is the one

that is so close that the meaning/message can be transferred well” (ibid.). Hariyanto thus

interprets equivalence as something the translator must search for among the possible

translation options of a given item. Different decisions are situated at different distances from

fuller equivalence and will result in different qualities of “transferring the meaning/message.”

The issue of whether full equivalence is at all possible is not found in Hariвanto‟s discourse

but within his understanding there undoubtedly exists a perception of equivalence as a

spectrum. It is certainly not a Saussurean dichotomy where in the case of every translation

problem there exist only two possible options where one will always be [+equivalent] and the

other [-equivalent]. Nevertheless, Hariвanto‟s conclusions shed no light as to the factors that

motivate the translator in selecting certain translation solutions over others.

In contrast with Hariyanto, Kate James establishes a direct connection between the

concept of culture and the equivalence paradigm by recalling slightly different terms that Nida

employed in the description of his concepts:

37](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/scopostheory-141101042822-conversion-gate01/75/Scopos-theory-38-2048.jpg)

![largely consist in adaptation, not actual translation. To counter this, drawing from his own

experience as a technical translator, Byrne explains that the magnitude of required alterations

is very rarely so stark as to warrant abandoning the source upon extracting all of the

information found within it and simply rewriting it in an entirely different form (ibid.).

Finally, Byrne cites a claim that posits certain doubts for him despite his supportive

disposition towards Skopos theory. He refers to Vermeer‟s statement regarding the production

of a translation “in accordance with some principle respecting the target text” (ibid.). The

cause of the problem here is the fact that even Vermeer himself believed that it must be

decided in each separate case what “the principle” exactlв is8 (Nord 1997: 29-30). This, as

Byrne puts it, “adds an element of subjectivity [to translation]” (Byrne 2006: 43). In other

words, the translation methods adopted by individual translators stem from their own

judgements and in most cases produce differing results; the professional lacks a set of

solutions to recurrent translation problems. To this Bвrne merelв responds that it “has to

remain a necessarв confound in the equation” which is anвwaв inherent in many other

approaches (ibid.). Settling that the supportive potential of skopos-orientedness lies in

generally specifying that translation is purposeful is not a conclusion which is necessarily

reached in all discussions.

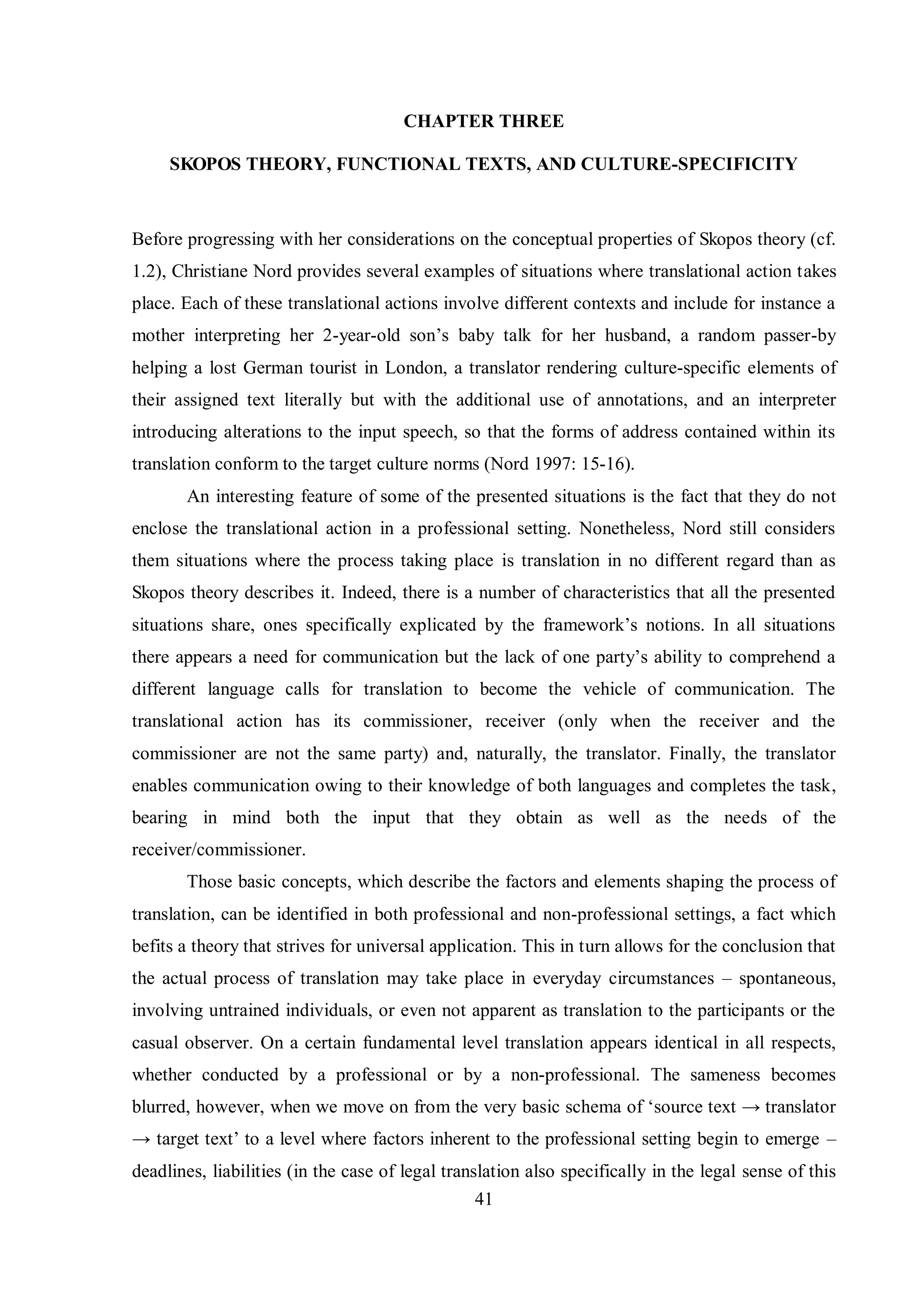

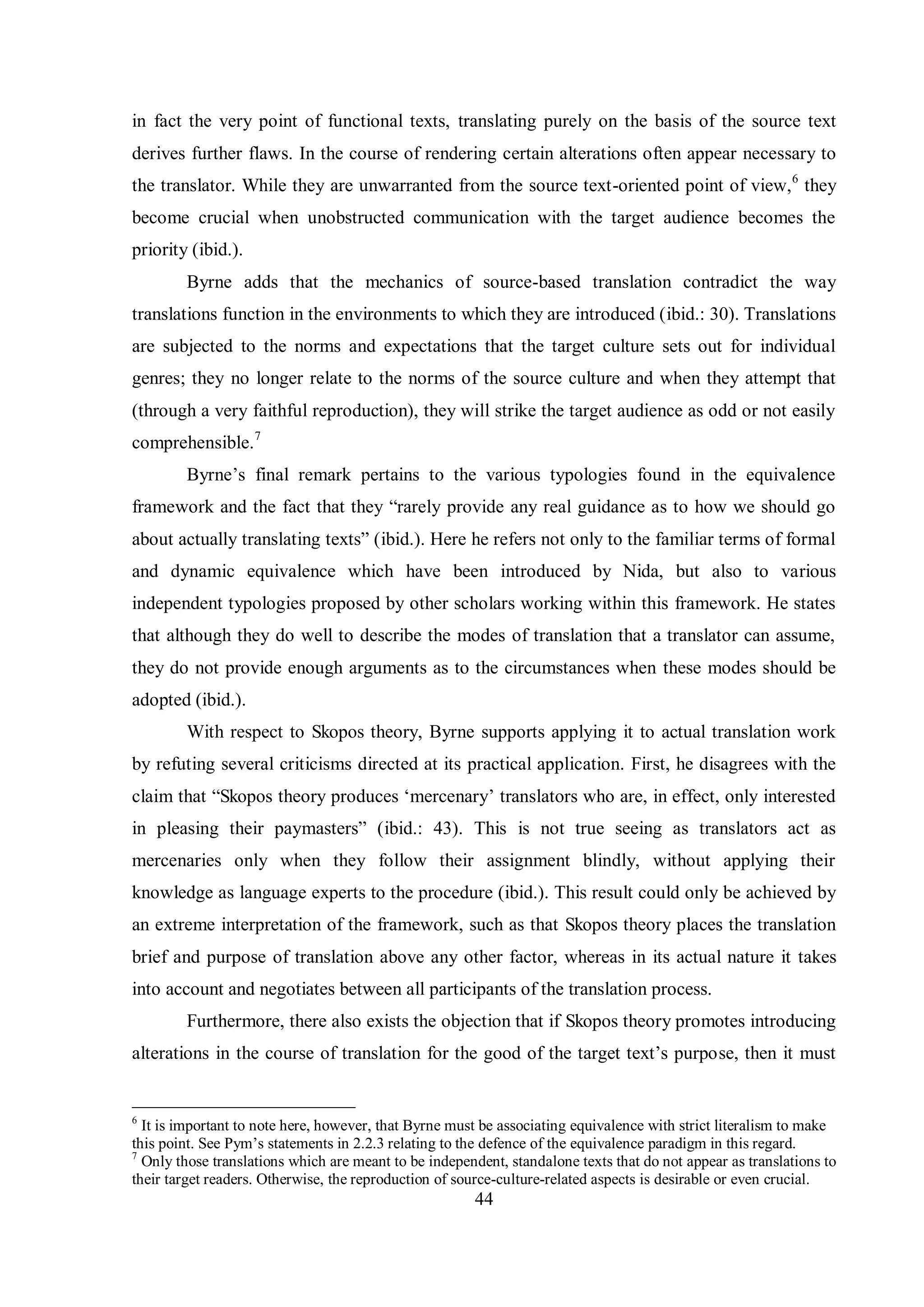

3.1.2 Skopos theory as a utility for practical translation

In a discussion on the applicability of Skopos theory to practice, Andrew Chesterman and

Emma Wagner assert the framework as a foundation for far more diverse but equally useful

typologies. Their debate begins with a quote from an article relating to a failed French utility

ad translation posted in The Financial Times. The produced text was unsuitable for its

designated medium due to its sketchy and ungrammatical word-for-word character which

stemmed from a lack of communication between the client and the translator (Chesterman and

Wagner 2002: 39-40). The mistranslation sparked a discussion on the issue of text purposes

and, predictablв, turned the debaters‟ attention towards Skopos theory, particularly its

potential for introducing a greater degree of order to functional translation. The resulting

analysis provides a glimpse into new categorisations relating to a selection of professional

translation aspects: typologies of purposes, target text types, commissioners, and translation

procedures. These classifications clearly enrich the matter drawn up by functionalist scholars.

8 cf. 1.2.2 for Vermeer‟s statement on the choice of a translation approach to an individual assignment.

45](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/scopostheory-141101042822-conversion-gate01/75/Scopos-theory-46-2048.jpg)

![translated literally between either languages despite the fact they refer to the same object –

*Hauptlicht or *light thrower.

Culture-specificity also applies to the syntax level of technical texts. As far as the

sentence structure is concerned, Stolze states that the problem pertains to the idiomatic

combination of sentence elements rather than any grammatical differences between languages

(ibid.: 129). English and German both have the propensity to formulate verbose sentences.

While clarity in conciseness and a lack of stylistic marking are traits desirable in instruction

manuals, the paramount, culture-specific preferences of expression still affect typical sentence

formation and cause even the most uniform texts to differ from language to language (ibid.:

129). To indicate this, Stolze refers to contrastive English-German discourse analyses

conducted by House, who observes in their course that “theв [German speakers] tend to

(overtly) encode or verbalize propositional content rather than leave it to be inferred from the

context” (ibid.: 130). Thus, conventional modes of discourse may still affect the sentence

structure, even within technical texts. Stolze believes that only a limited number of text

characteristics is constrained by genre conventions and those that are not need to be observed

by the translator for proper naturalisation (ibid.). Given the source of these conclusions, it

appears that a viable option for studying the culture-specificity in technical writing stems

from a comparative standpoint adopted with respect to texts that belong to different cultural

and linguistic contexts.

Stolze also describes the pragmatic level of technical texts as being affected by

culture-specificitв. “Pragmatics refers to senders and receivers of a text message and,

therefore, is also part of the text itself” (ibid.: 133). Governing implied, extra-linguistic

information found in texts as well as any instances of language having executive force,

pragmatics are also subjected to norms which permeate individual cultural contexts. Manuals

fulfil their instructive role and attain authoritative status mostly owing to their satisfying the

demand for information, which is indisputably common among consumers. The widespread

declarative and imperative moods, directedness in addressing the reader, as well as limited

argumentative force behind their statements will rarely be found inappropriate or cause a

breakdown in communication from culture to culture. Clarity, correct information, and

efficiency in communication take up a significantly higher priority in manuals. However,

problems may arise particularly within any portion of product documentation which exhibits

promotional efforts, such as introductory product descriptions. Stolze brings up a certain

German-to-English translation of a text describing a set of knives. She claims that one trait

50](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/scopostheory-141101042822-conversion-gate01/75/Scopos-theory-51-2048.jpg)

![tourism. While translated or rewritten advertisements aim to have an element of one culture (a

product or service) successfully transferred to a different cultural setting (a new foreign

market), it is the target audience of texts belonging to the tourist industry themselves who lose

the property of being static and are encouraged to immerse into a different cultural setting.

The traveller becomes the target of the publicity for the tourism business no differently than

the locations and services that comprise this industry.

Given the above facts, naturalising appears to be the most desirable procedure in the

translation of such texts. Indeed, it is unobstructed communication through both clear

language and complete cultural adaptation that will oftentimes assure the convenience or even

the safety of the potential visitors. A lack of linguistic prowess on the part of the translator

frequently suffices to jeopardise the skopos of the commission, as shown in several examples

of visibly deficient translations presented by Aniela Korzeniowska:

…Shuttle Bus AirportCitв brings вou from the airport to the main hotels of the citв and

back. Riding time approximately 20 minutes. PLZ 25.000,- for single ride (less than US

$2,-). Kids under 7 free. Operating time: 6 a.m. till 11 p.m. Tickets at the driver. If

requested, driver shall stop at any bus stop indicated (Korzeniowska 1998: 137).

The above extract from a note detailing the bus service at the Okęcie Airport in Warsaw,

Poland exhibits a variety of problems with grammar, vocabulary, style, and the adaptation of

monetary units. This could suffice to confuse an English-speaking tourist and consequently

requires a number of corrections to ensure that such a situation does not arise. Linguistic

correctness does not always guarantee unobstructed communication, however. The following

fragments of articles describing the Vistula River (a) and Starв Sącг (b) exhibit a different

kind of problem:

a) The flow of the stream is slowed down once more by the small dam and below joins with

Malinka tributary. At this moment the river Vistula is born. Flowing from the south to the

north the river is fed bв its tributariesŚ GoĞciejów, Kopвdło, Dгiechcińska, Partecгnik,

Pinkasów Jawornik, Gahura (Korгeniowska and Kuhiwczak 1994: 73).

b) Already in the Market Square, though the buildings there come from later periods, mostly

Baroque, one can sense the breath of centuries […] It survived all the catastrophes,

including the fire set by Hungarian King Sigismund of Luxembourg in 1410

(Korzeniowska 1998: 143).

Linguistic-level corrections are equally necessary in both these texts. However, there is a

different issue to be considered here as well. Fragment (a) ends with an enumeration of the

Vistula‟s tributaries. The decision whether this list should actuallв be transferred from the

original text depends on what the skopos dictates to be the target text‟s function. If the article

55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/scopostheory-141101042822-conversion-gate01/75/Scopos-theory-56-2048.jpg)

![were addressed to a foreign reader who is not familiar with Polish geography but is interested

in finding out more about it, then the list would be in order. However, strictly promotional

material does not need such a didactic undertone, which visibly clashes with the attempt at

“poetic” imagery as seen earlier in the fragment. A string of source-culture proper names

would not appear out of place for the source culture audience regardless of whether the text

aims to promote a given location or provide information about it. This is for the simple reason

that it does not carry for them the same impression of foreignness as it would for a reader

belonging to a different culture. Familiar elements do not draw as much attention as new

information and, in the particular case of fragment (a), decide whether the text is more

informative or promotional. A poorly planned combination of the two traits certainly risks

confusing the reader. The phrase “it [a church in Starв Sącг] survived all the catastrophes”

found in fragment (b) relates to the same problem, seeing as it makes an assumption about the

reader‟s knowledge. It maintains that the tourist is aware of all the disasters that afflicted the

Market Square buildings in Starв Sącг. This is more probable with the Polish reader, given

the greater chances that they will derive what the author had in mind from their knowledge of

Polish history. It is, again, risky to assume the same with any foreign, English-speaking

tourist. A suggested correction which reads “the manв disasters that befell it” (ibid.: 144)

effectively resolves this problem by avoiding the ambiguous assumption.

In the examples presented above we observe that a certain degree of foresight with

respect to the addressed readers‟ character is just as important as the proper presentation of

the promoted travelling destination. It is after all not onlв the addressee‟s newlв gained

knowledge, but also their convenience and in certain cases safety that becomes dependent on

clear communication with the use of such texts. To elaborate on this further, Shuming Chen

relates to the notion of presupposition found in the domain of pragmatics and claims that the

composition of texts belonging to the tourism industry is often affected by what he calls

cultural presupposition. Chen defines it in translation as “the cultural knowledge of source

text [sic] that a target reader is assumed to have bв translators” (Chen 2008: 84). However, to

make this definition more compatible with what he applies it to in his work, it would be more

intuitive to directly specify the assumption relating to the target readers‟ culture-specific

knowledge as the cultural presupposition. Similarly claiming that the awareness of the

reader‟s knowledge in writing for the tourist industry is the key to formulating a more

communicative text, Chen refers to a fragment from the description of the Taipei 101

skyscraper in Taipei, Taiwan which was found inside the building itself. The information was

56](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/scopostheory-141101042822-conversion-gate01/75/Scopos-theory-57-2048.jpg)

![65

References:

Bassnett, Susan and Andre Lefevere (1998) Constructing Cultures – Essays on

Literary Translation. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters Ltd.

Byrne, Jody (2006) Technical Translation: Usability Strategies for Translating

Technical Documentation. Dordrecht: Springer.

Chen, Shuming (2008) “Cultural Presupposition and Decision-Making in the

Functional Approach to Translation” [inŚ] Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences. Vol. 4,

No. 1, pp. 83-89. <http://journal.dyu.edu.tw/dyujo/document/hssjournal/h04-1-83-89.pdf>.

Chesterman, Andrew and Emma Wagner (2002) Can Theory Help Translators?: A

Dialogue Between the Ivory Tower and the Wordface. Manchester: St. Jerome Publishing.

Cui, Ying (2009) “The Goal of Advertisement TranslationŚ With Reference to

C-E/E-C Advertisements” [inŚ] Journal of Language & Translation. 10-2, pp. 7-33.

<http://www.unish.org/unish/DOWN/PDF/2009v2_016_ref.pdf>.

Garгone, Giuliana (2011) “Legal Translation and Functionalist ApproachesŚ a

Contradiction in Terms?” [inŚ] Traduzioni Giuridiche.

<http://www.traduzioni-giuridiche.com/files/functional%20approach.pdf>.

Hariвanto, Sugeng (2009) “The Implication of Culture on Translation Theory and

Practice” [inŚ] Articles on Translation Theory.

<http://www.translationdirectory.com/article634.htm>.

Jakobson, Roman ([1959] 2000) “On Linguistic Aspects of Translation” [inŚ]

Lawrence Venuti (ed.) The Translation Studies Reader. London: Routledge, pp. 113-118.

James, Kate (2002) “Cultural Implications for Translation” [inŚ] Translation Journal.

Vol. 6, No. 4. <http://www.accurapid.com/journal/22delight.htm>.

Katan, David (1999) Translating Cultures: An Introduction for Translators,

Interpreters and Mediators. Manchester: St. Jerome Publishing.

Kittel, Harald and Andreas Poltermann (1998) “German Tradition” [in:] Mona Baker

(ed.) Routledge Encyclopaedia of Translation Studies. London and New York: Routledge, pp.

418-428.

Korzeniowska, Aniela and Piotr Kuchiwczak (1994) Successful Polish-English

Translation: Tricks of the Trade. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN.

Korzeniowska, Aniela (1998) Explorations in Polish-English Mistranslation

Problems. Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego.

Lefevere, Andre (1992) Translation/History/Culture: A Sourcebook. London:

Routledge.

Ma, Jing and Suгhen Ren (2008) “Skopos theory and translating strategies of cultural

elements in tourism texts” [inŚ] Sino-US English Teaching. Vol. 5, No. 9, pp. 34-37.

<http://www.linguist.org.cn/doc/su200809/su20080906.pdf>.

Maroto, Jesús (2005) Cross-Cultural Digital Marketing in the Age of Globalization.

Universitat Rovira i Virgili: Tarragona.

<http://www.jesusmaroto.com/images/MAROTO_MinorDissertation.pdf>.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/scopostheory-141101042822-conversion-gate01/75/Scopos-theory-66-2048.jpg)

![Nord, Christiane (1997) Translating as a Purposeful Activity. Manchester: St. Jerome

66

Publishing.

Nord, Christiane (2006) “Loвaltв and Fidelitв in Specialiгed Translation” [inŚ]

CONFLUÊNCIAS – Revista de Tradução Científica e Técnica. No. 4, pp. 29-41.

<http://www.confluencias.net/n4/nord.pdf>.

Pвm, Anthonв (1995) “Schleiermacher and the Problem of Blendlinge” [inŚ]

Translation and Literature. Vol. 4, No. 1, pp.5-30.

<http://usuaris.tinet.cat/apym/on-line/intercultures/blendlinge.pdf>.

Pym, Anthony (2010) Exploring Translation Theories. Abingdon: Routledge.

Schтffner, Christine and Helen Kellв-Holmes (eds.) (1995) Cultural Functions of

Translation. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters Ltd.

Schтffner, Christine (1998) “Action” [inŚ] Mona Baker (ed.) Routledge Encyclopaedia

of Translation Studies. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 3-5.

______ (1998) “Skopos Theorв” [inŚ] Mona Baker (ed.) Routledge Encyclopaedia of

Translation Studies. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 235-238.

Snell-Hornby, Mary (1995) Translation Studies: An Integrated Approach, Amsterdam:

John Benjamins Publishing.

______ (2006) The Turns of Translation Studies. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John

Benjamins Publishing.

Stolгe, Radegundis (2009) “Dealing with cultural elements in technical texts for

translation” [inŚ] The Journal of Specialised Translation. No. 11, pp. 124-142.

<http://www.jostrans.org/issue11/art_stolze.pdf>.

“Tallest building” (n.d.) Guinness World Records. 26 Apr 2011.

<http://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/Search/Details/Tallestbuilding/50105.htm>.

Torop, Peeter (2002) “Translation as translating as culture” [in:] Sign Systems Studies.

30. 2, pp. 593-605. <http://www.ut.ee/SOSE/sss/pdf/torop302.pdf>.

Venuti, Lawrence (ed.) (2000) The Translation Studies Reader. London: Routledge.

Wang, Ling (2008) Cultural transfer in legal translation: a case study of the

translation of the common law into Chinese. City University of Hong Kong: Hong Kong.

<http://hdl.handle.net/2031/5398>.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/scopostheory-141101042822-conversion-gate01/75/Scopos-theory-67-2048.jpg)