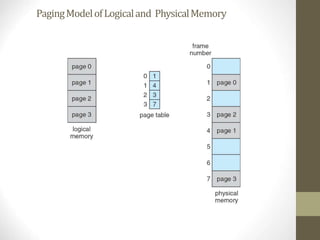

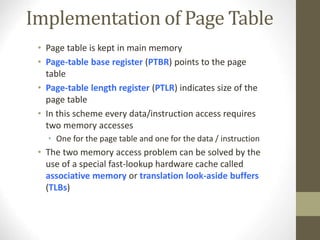

Chapter 8 discusses various memory management techniques, including swapping, contiguous allocation, segmentation, and paging, with a focus on their implementation and hardware support. It also covers concepts like address binding, logical versus physical address spaces, and the impact of fragmentation on memory allocation. Examples from Intel and ARM architectures illustrate these memory management methods and their application in operating systems.