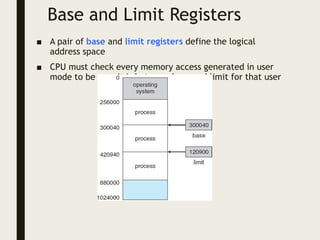

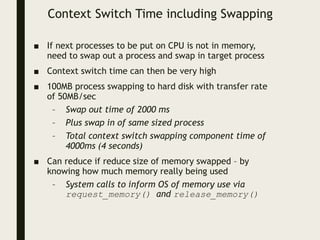

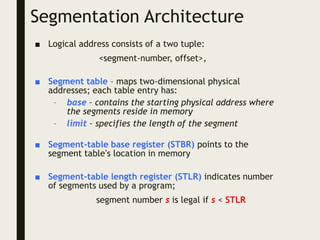

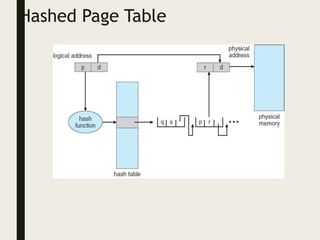

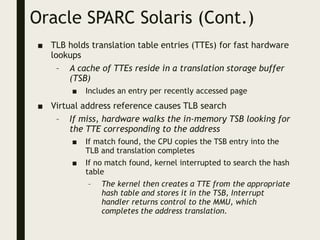

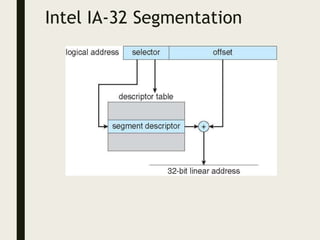

This document provides an overview of memory management techniques, including paging and segmentation. It discusses how programs are loaded into memory and placed within a process. It describes the memory management unit (MMU) that maps virtual to physical addresses using techniques like paging, segmentation, and swapping. Paging divides memory into fixed-size pages and uses a page table to translate logical addresses to physical frame numbers. Segmentation divides a program into logical segments and uses segment tables to map two-dimensional logical addresses to physical addresses.