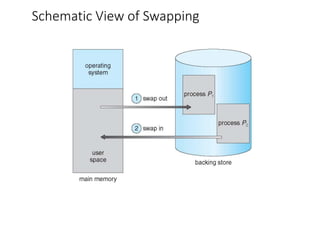

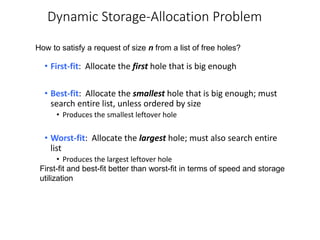

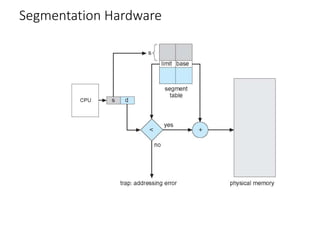

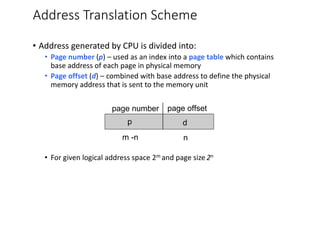

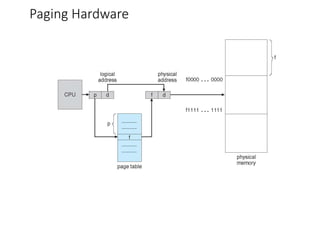

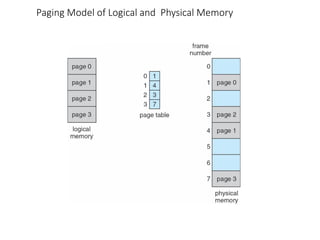

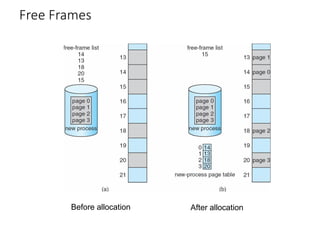

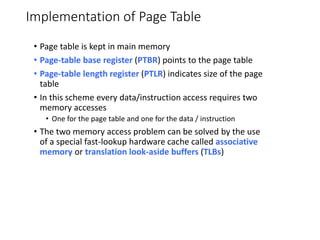

This chapter discusses various memory management techniques used in computer systems, including segmentation, paging, and swapping. Segmentation divides memory into variable-length logical segments, while paging divides it into fixed-size pages that can be mapped to non-contiguous physical frames. Paging requires a page table to map virtual to physical addresses and allows processes to exceed physical memory by swapping pages to disk. The chapter describes address translation hardware like TLBs, protection mechanisms, and issues like fragmentation.