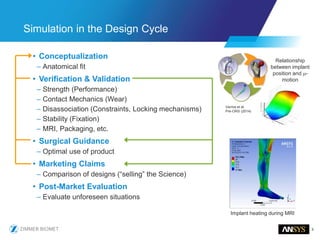

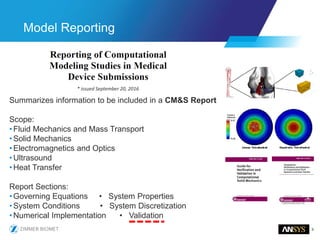

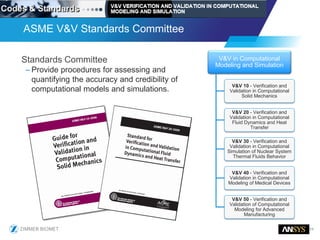

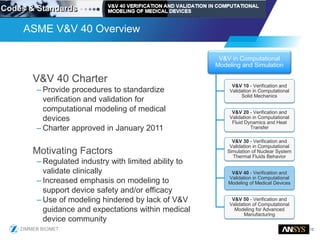

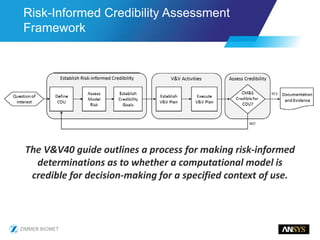

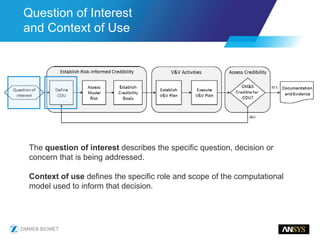

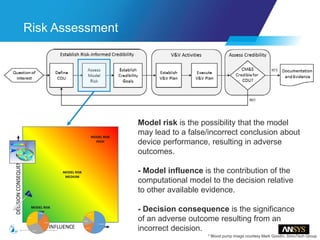

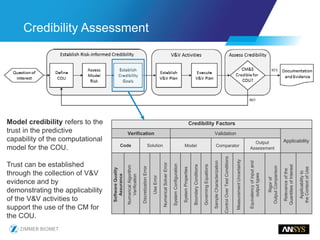

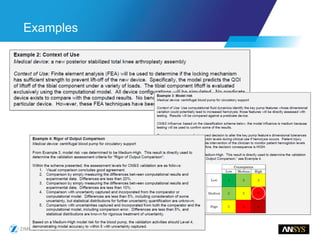

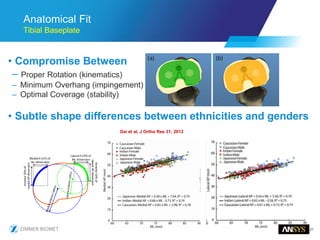

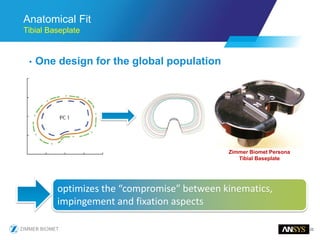

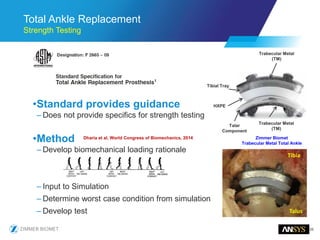

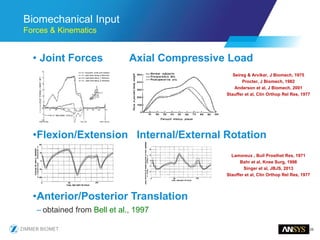

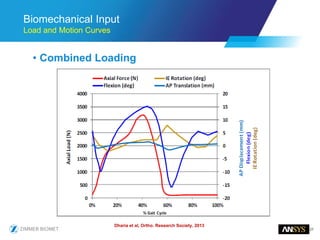

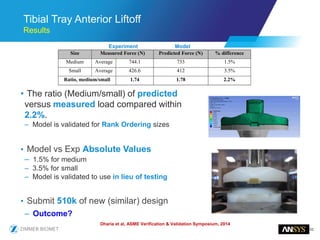

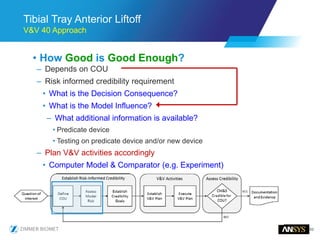

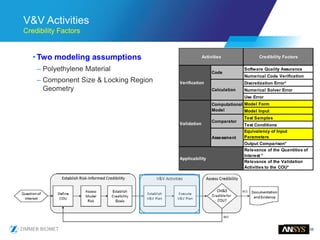

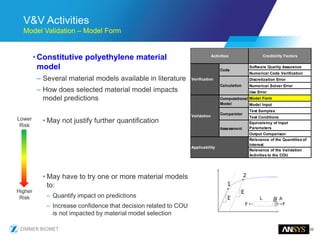

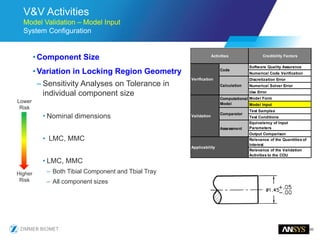

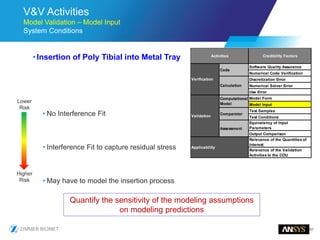

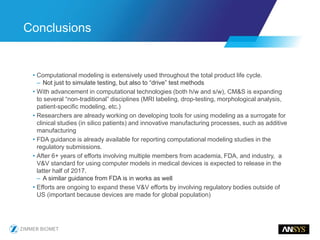

The document discusses the role of computational modeling and simulation (CM&S) in the total product lifecycle of orthopedic devices, emphasizing its use in device design, regulatory submission processes, and post-market evaluation. Key aspects include verification and validation (V&V) standards, the impact of regulatory frameworks, and how these models can predict device performance to improve safety and efficacy. Challenges and opportunities within the context of using CM&S for medical devices, including addressing uncertainties and leveraging real-world evidence, are also explored.