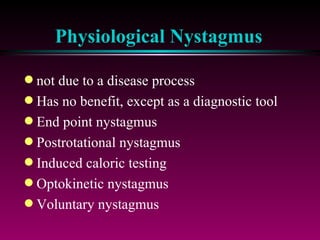

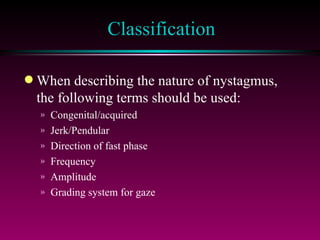

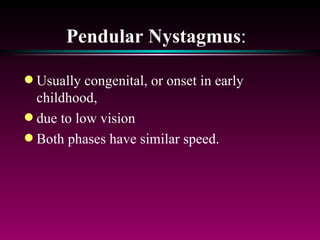

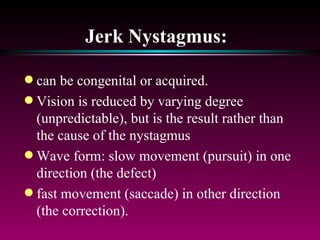

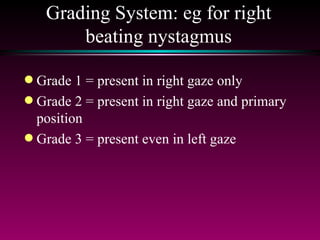

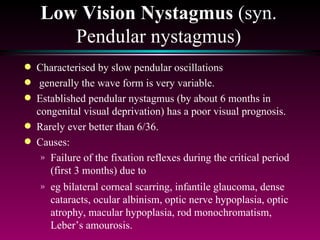

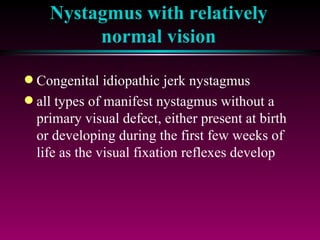

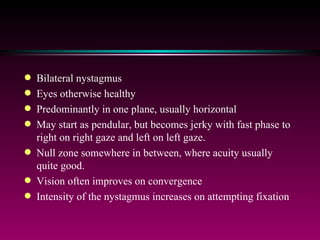

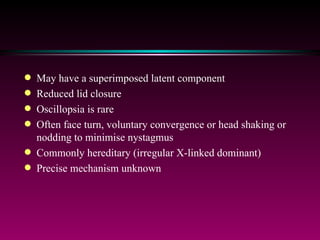

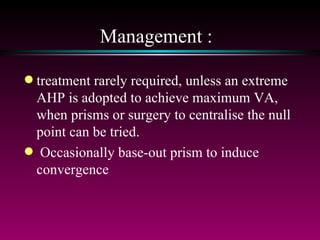

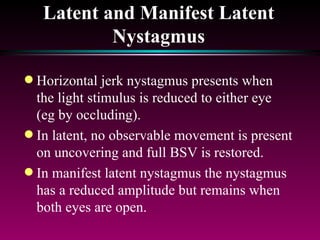

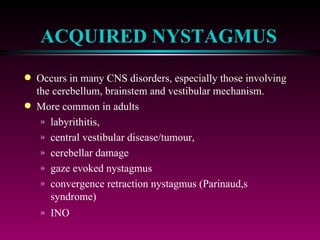

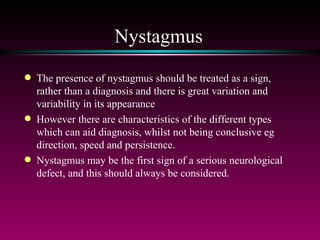

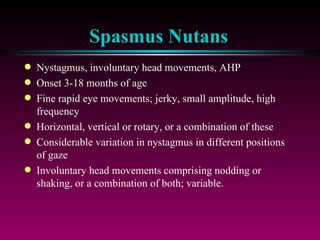

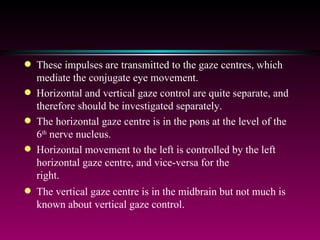

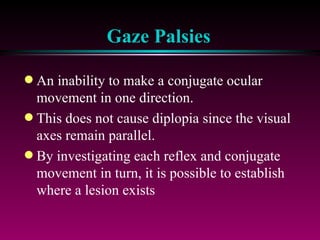

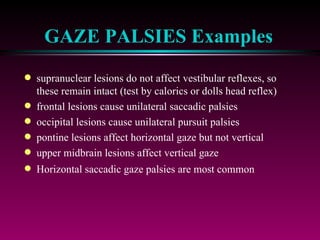

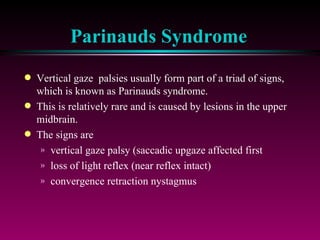

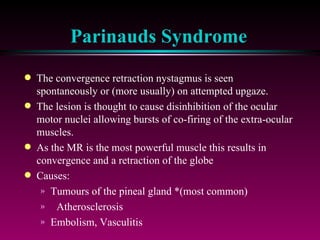

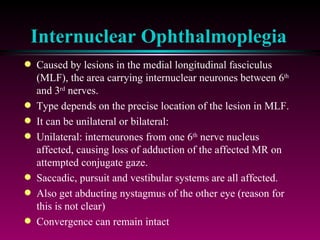

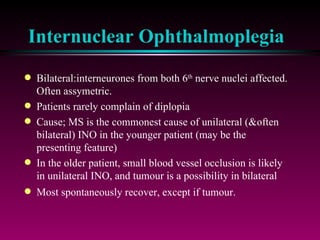

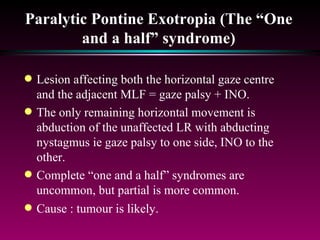

This document summarizes different types of nystagmus including physiological nystagmus, pathological nystagmus, pendular nystagmus, jerk nystagmus, latent nystagmus, acquired nystagmus, and discusses grading systems, congenital nystagmus, low vision nystagmus, nystagmus with relatively normal vision, bilateral nystagmus, spasmus nutans, see-saw nystagmus, supranuclear gaze control, gaze palsies, Parinaud's syndrome, internuclear ophthalmoplegia, and paralytic pontine exotropia.