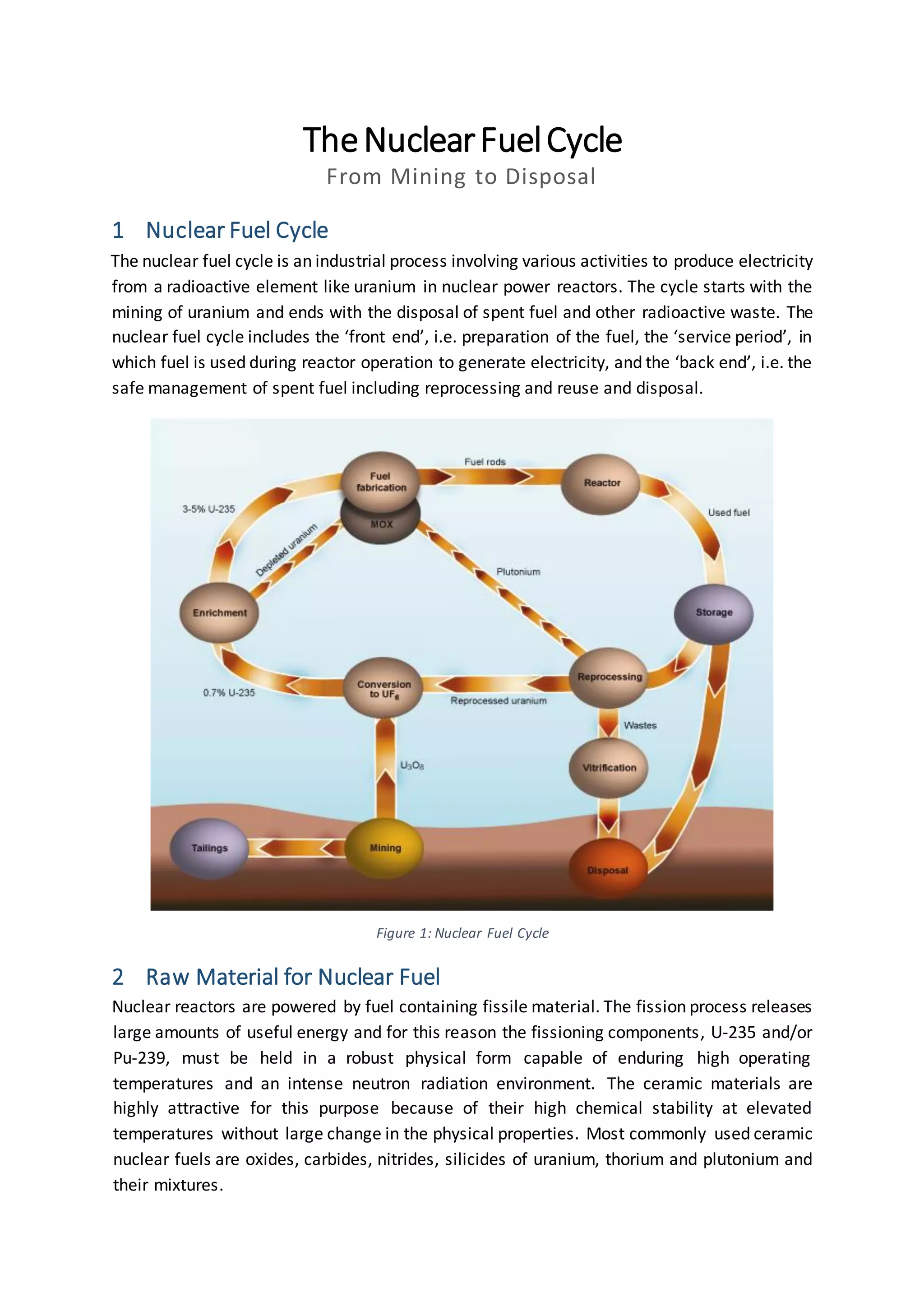

The document discusses the nuclear fuel cycle from mining uranium to disposal of spent nuclear fuel. It covers the front end which includes mining, milling, conversion, enrichment and fuel fabrication. Uranium dioxide (UO2) pellets are commonly used as fuel and are fabricated using powder metallurgy techniques. The fuel is used in reactors to generate electricity via fission before being stored and potentially reprocessed to extract uranium and plutonium for reuse.