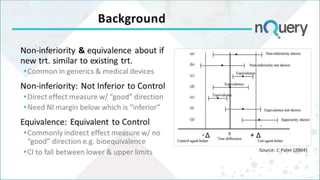

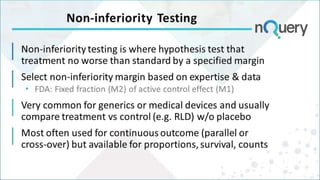

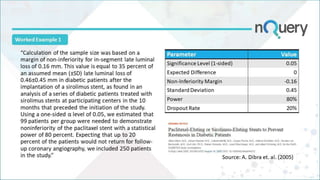

The document discusses non-inferiority and equivalence trial designs, focusing on statistical considerations and sample size calculations for clinical trials. It highlights methods for testing whether new treatments are comparable to existing treatments, including fixed margin approaches and the two one-sided tests for bioequivalence. The document also details worked examples and considerations for trial design, emphasizing FDA guidelines and statistical power requirements.