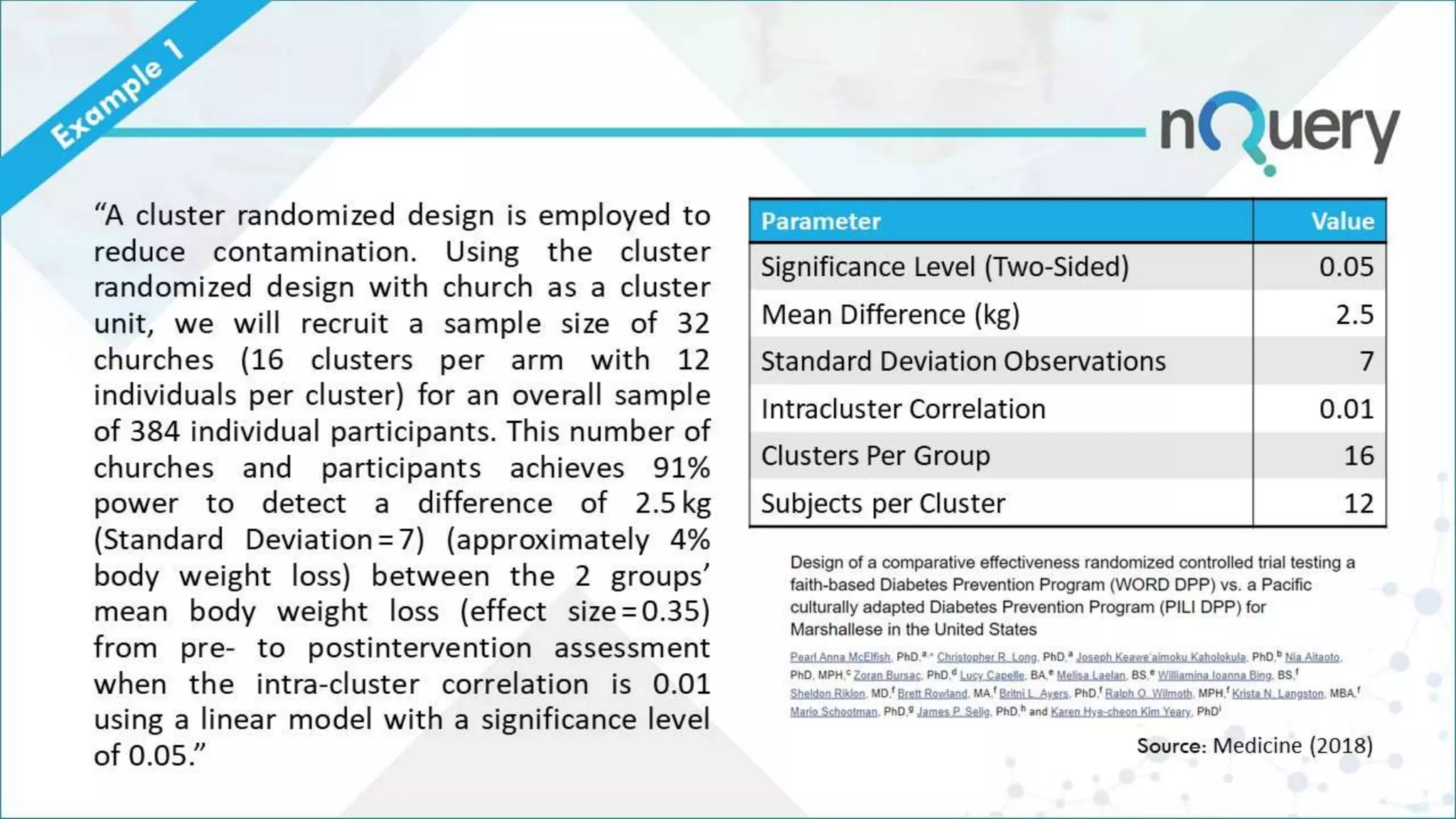

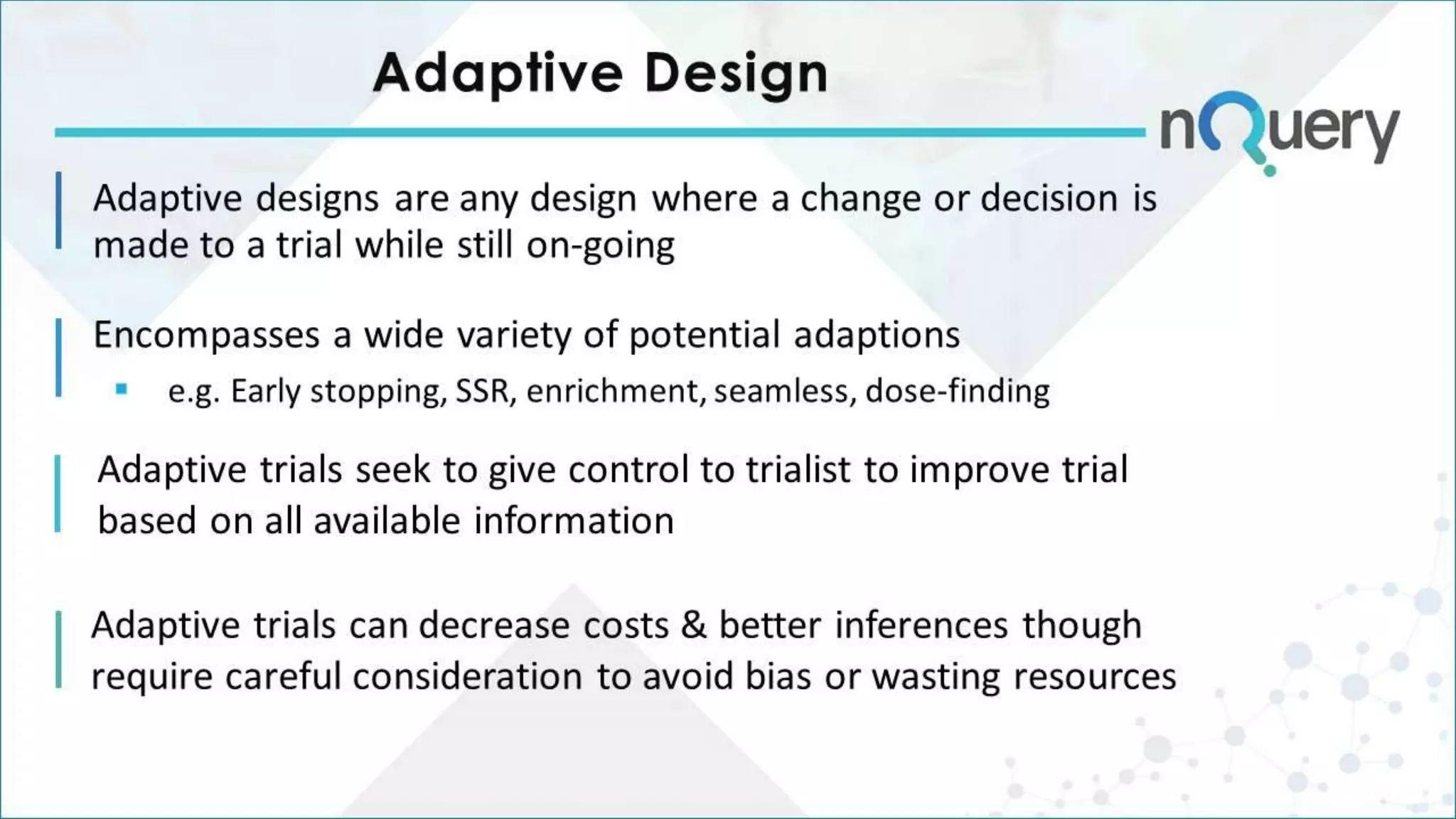

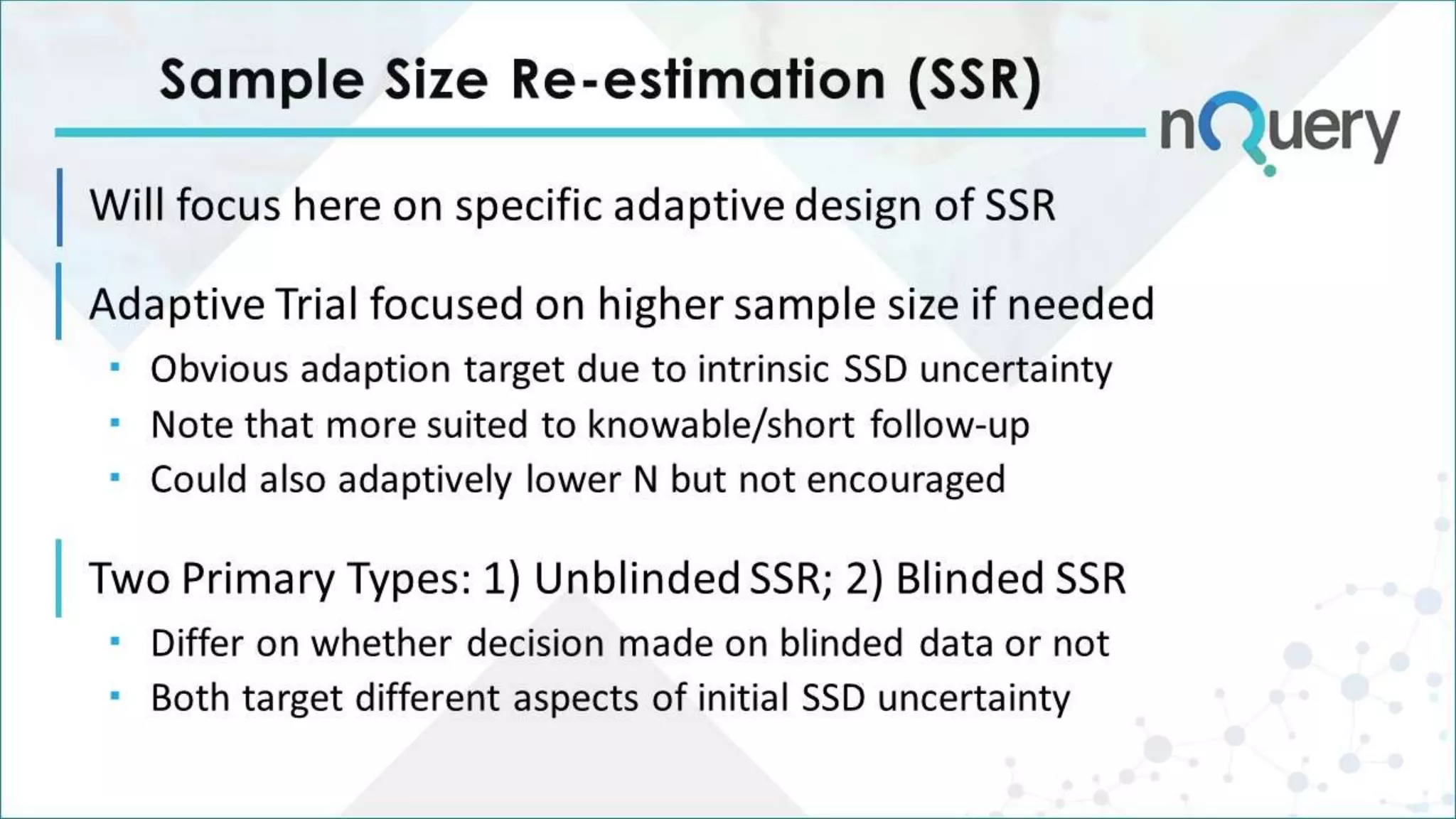

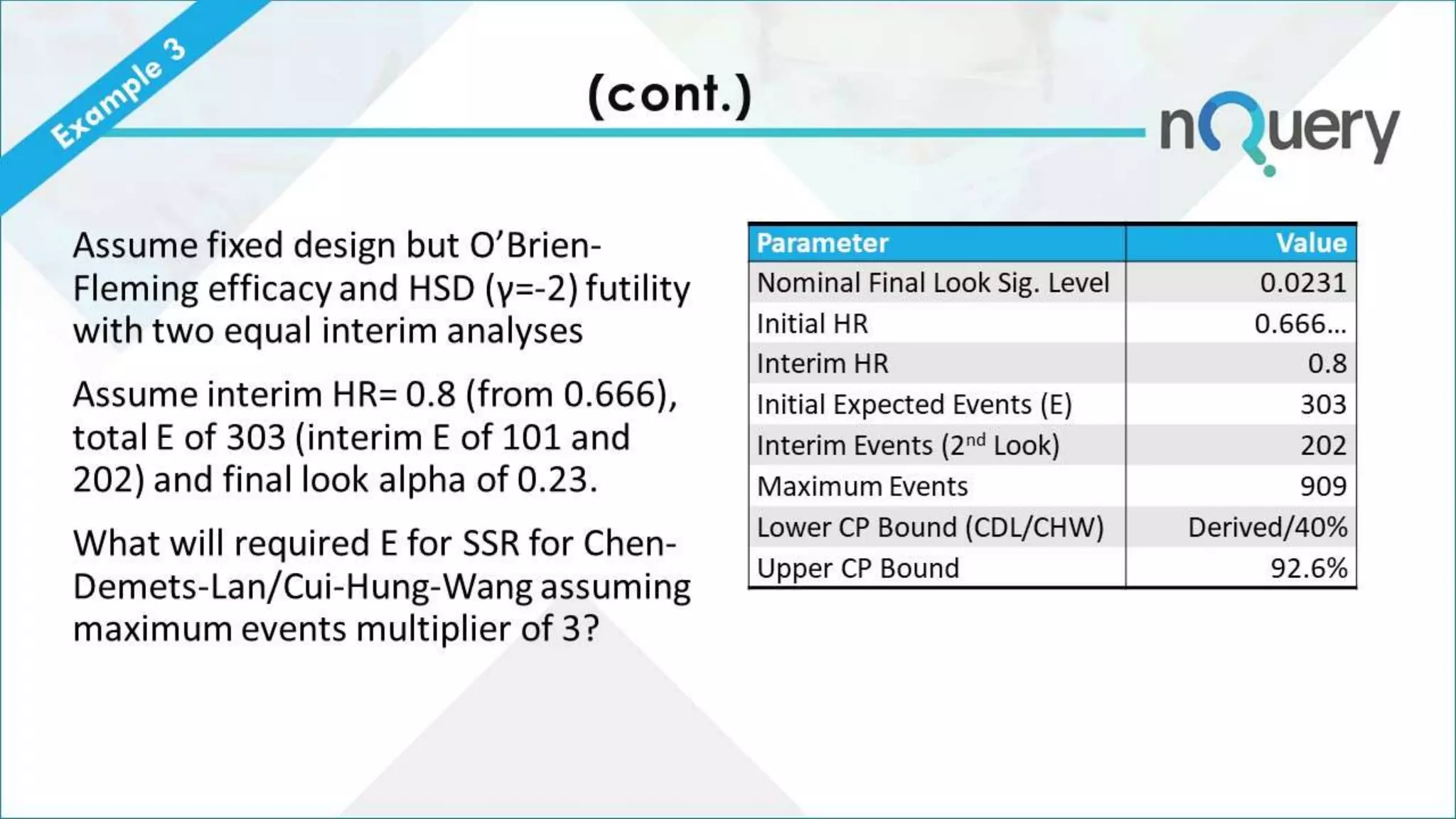

The document provides an overview of the design challenges and statistical considerations involved in clinical trials, emphasizing the high costs and low success rates in drug development. It discusses the need for flexibility in trial design, including adaptive methods and sample size re-estimation, to improve efficiency and better meet regulatory expectations. Additionally, the document highlights the importance of stakeholder collaboration and the proper application of statistical models to enhance trial outcomes.