The document discusses the natural gradient method for optimizing neural networks. It explains that the natural gradient finds the direction of steepest descent in function space rather than parameter space. The natural gradient is invariant to reparameterization. For most neural networks, natural gradient descent is equivalent to a second-order optimization method called the generalized Gauss-Newton method. The natural gradient takes into account the geometry of the parameter space defined by the Fisher information matrix.

![4 / 18

Gradient Descent

The gradient descent update

∆θ = −α θL

is the solution to the following optimization problem:

arg min

∆θ

[ θL(θ) · ∆θ]

s.t. ∆θ ≤ δ.

We are optimizing a linear approximation of L within a trust region

defined by the Euclidean metric in parameter space.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/natgrad-180314064506/75/New-Insights-and-Perspectives-on-the-Natural-Gradient-Method-4-2048.jpg)

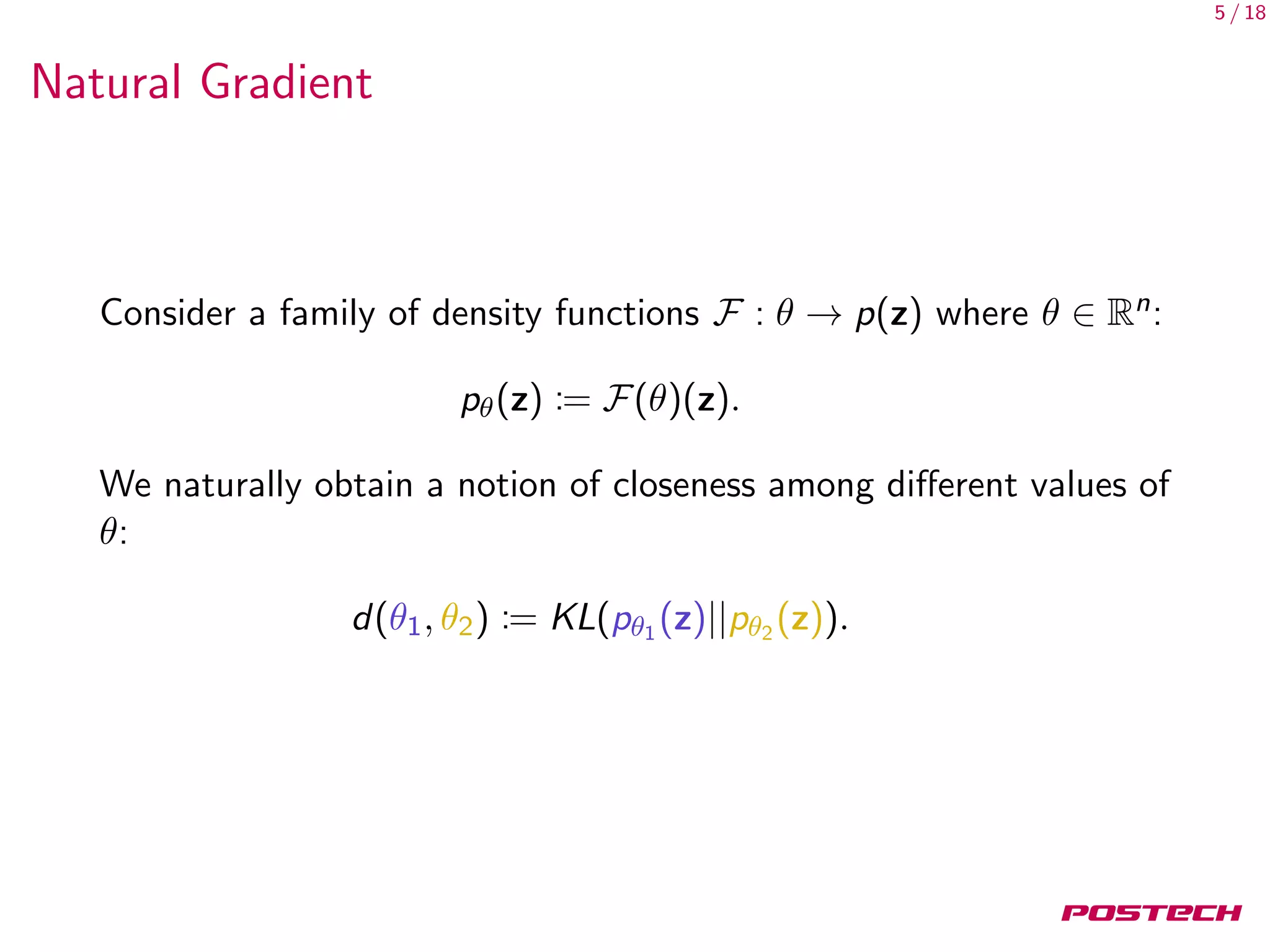

![6 / 18

Natural Gradient

d(θ1, θ2) := KL(pθ1 (z)||pθ2 (z)).

Let’s see how d behaves near a given θ.

KL(pθ(z)||pθ+∆θ(z)) = Ez [log pθ] − Ez [log pθ]

−Ez [ log pθ] ∆θ + O(∆θ2

)

= O(∆θ2

),

so no useful information from first order approximation.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/natgrad-180314064506/75/New-Insights-and-Perspectives-on-the-Natural-Gradient-Method-6-2048.jpg)

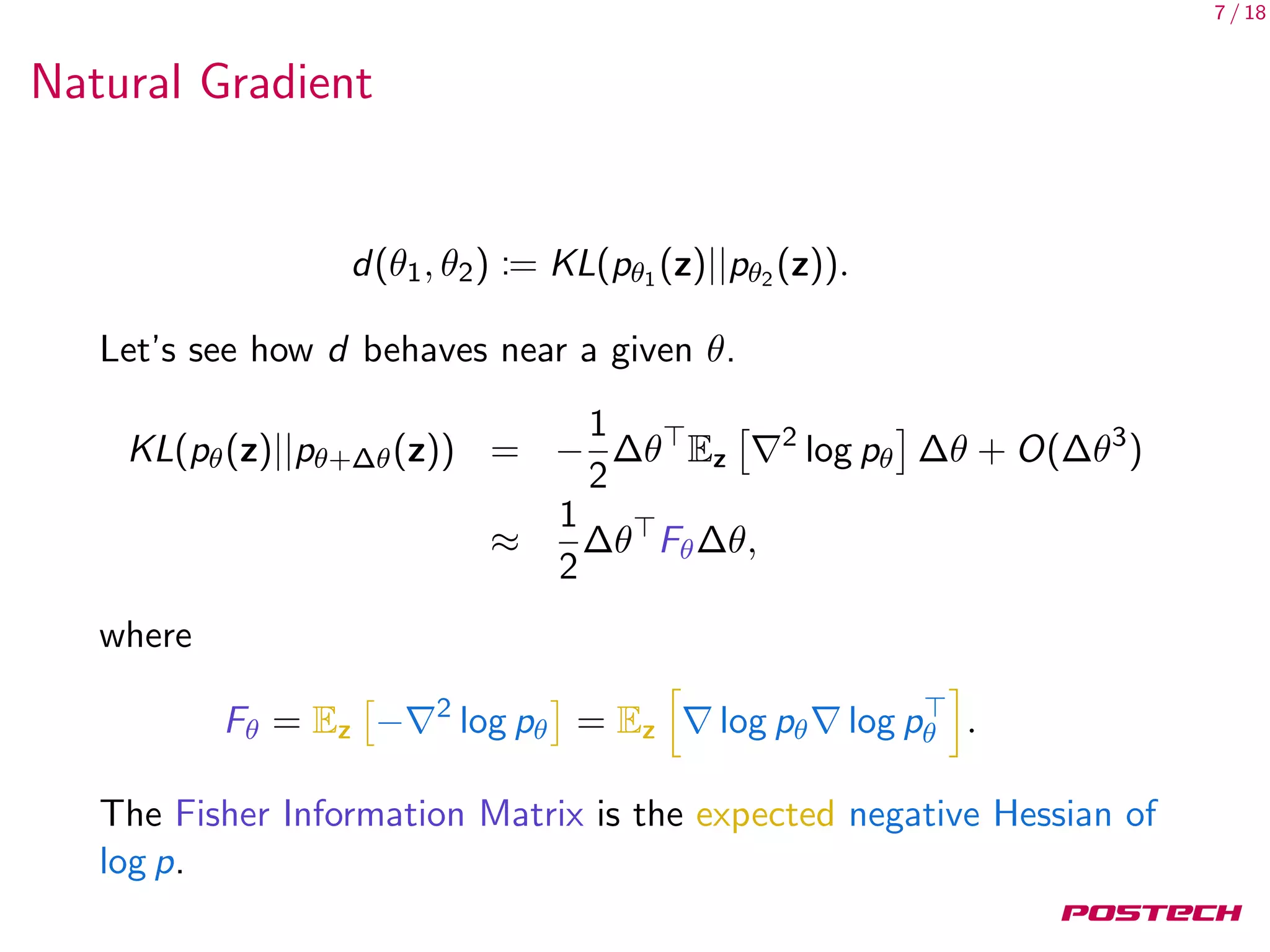

![8 / 18

Natural Gradient

We change the constraint of

arg min

∆θ

[ θL(θ) · ∆θ]

s.t. ∆θ = const

to

s.t.KL(pθ(z)||pθ+∆θ(z)) = const.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/natgrad-180314064506/75/New-Insights-and-Perspectives-on-the-Natural-Gradient-Method-8-2048.jpg)

![9 / 18

Natural Gradient

We change the constraint of

arg min

∆θ

[ θL(θ) · ∆θ]

s.t. ∆θ = const

to

s.t.KL(pθ(z)||pθ+∆θ(z)) = const.

Solution after using Lagrange multiplier

θL(θ) · ∆θ +

1

2

λ∆θ Fθ∆θ

is

∆θ ∝ F−1

θ θL](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/natgrad-180314064506/75/New-Insights-and-Perspectives-on-the-Natural-Gradient-Method-9-2048.jpg)

![14 / 18

Second-order Optimization

Why G instead of H

G is positive semidefinite, H is not.

Let’s expand H further, assuming f is a feedforward neural

network:

· · ·

Wi

−−→ si

φ

−→ ai

Wi+1

−−−→ si+1 · · ·

H − G =

l

i=1

mi

j=1

( ai L) Jsi

H[φ(si )]j

Jsi

The remaining term is the sum of curvature terms coming

from each intermediate activation. These curvature terms are

subject to more frequent change.

In ReLU networks, H[φ(si )] = 0 a.e..](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/natgrad-180314064506/75/New-Insights-and-Perspectives-on-the-Natural-Gradient-Method-14-2048.jpg)

![16 / 18

F and G

We know that F = G when FR = HL. When does this occur?

Let L(y, z) = − log r(y|z).

FR = −ERy|f (x,θ)

[Hlog r ]

HL = −E(x,y) [Hlog r ]

∴ FR = HL holds when ERy|f (x,θ)

[Hlog r ] = E(x,y) [Hlog r ]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/natgrad-180314064506/75/New-Insights-and-Perspectives-on-the-Natural-Gradient-Method-16-2048.jpg)

![17 / 18

F and G

We know that F = G when FR = HL. When does this occur?

Let L(y, z) = − log r(y|z).

FR = −ERy|f (x,θ)

[Hlog r ]

HL = −E(x,y) [Hlog r ]

∴ FR = HL holds when ERy|f (x,θ)

[Hlog r ] = E(x,y) [Hlog r ]

This holds when r(y|z) is an exponential family:

log r(y|z) = z T(y) − log Z(z)

since in this case, the hessian Hlog r does not depend on y.

Most commonly-used losses satisfy this property, including the

MSE loss and cross-entropy loss.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/natgrad-180314064506/75/New-Insights-and-Perspectives-on-the-Natural-Gradient-Method-17-2048.jpg)

![19 / 18

References I

[1] Shun-Ichi Amari. “Natural Gradient Works Efficiently in

Learning”. In: Neural Comput. (1998).

[2] James Martens. “Deep learning via Hessian-free

optimization”. In: Proceedings of the International Conference

on Machine Learning (ICML) (2010).

[3] James Martens. New insights and perspectives on the natural

gradient method. Preprint arXiv:1412.1193. 2014.

[4] James Martens and Roger B. Grosse. “Optimizing Neural

Networks with Kronecker-factored Approximate Curvature”.

In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine

Learning (ICML) (2015).

[5] Hyeyoung Park, Shun-Ichi Amari, and Kenji Fukumizu.

“Adaptive natural gradient learning algorithms for various

stochastic models”. In: Neural Networks (2000).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/natgrad-180314064506/75/New-Insights-and-Perspectives-on-the-Natural-Gradient-Method-19-2048.jpg)

![20 / 18

References II

[6] Razvan Pascanu and Yoshua Bengio. “Revisiting Natural

Gradient for Deep Networks”. In: Proceedings of the

International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR)

(2014).

[7] Oriol Vinyals and Daniel Povey. “Krylov Subspace Descent for

Deep Learning”. In: Proceedings of the International

Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics (AISTATS)

(2012).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/natgrad-180314064506/75/New-Insights-and-Perspectives-on-the-Natural-Gradient-Method-20-2048.jpg)