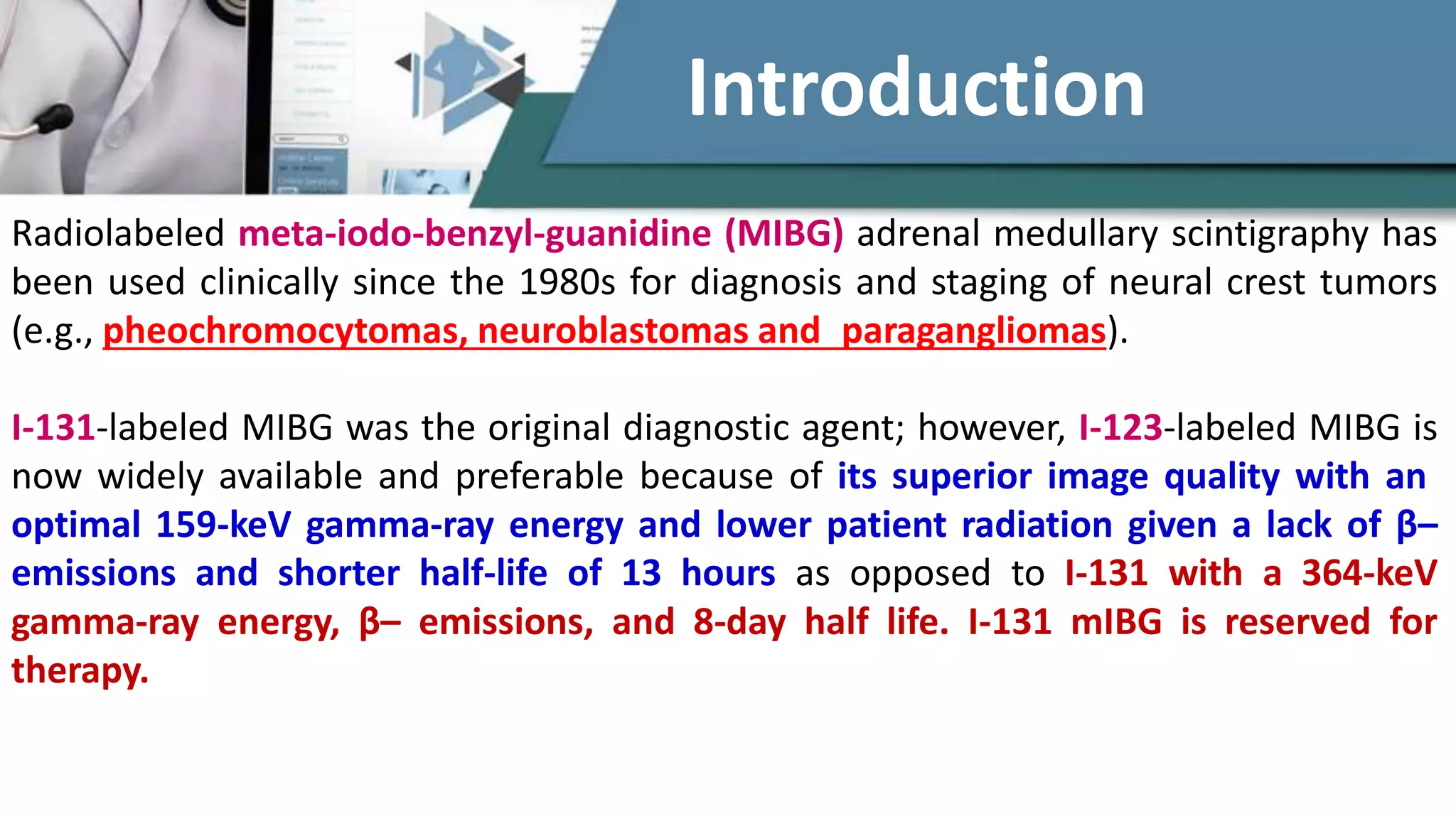

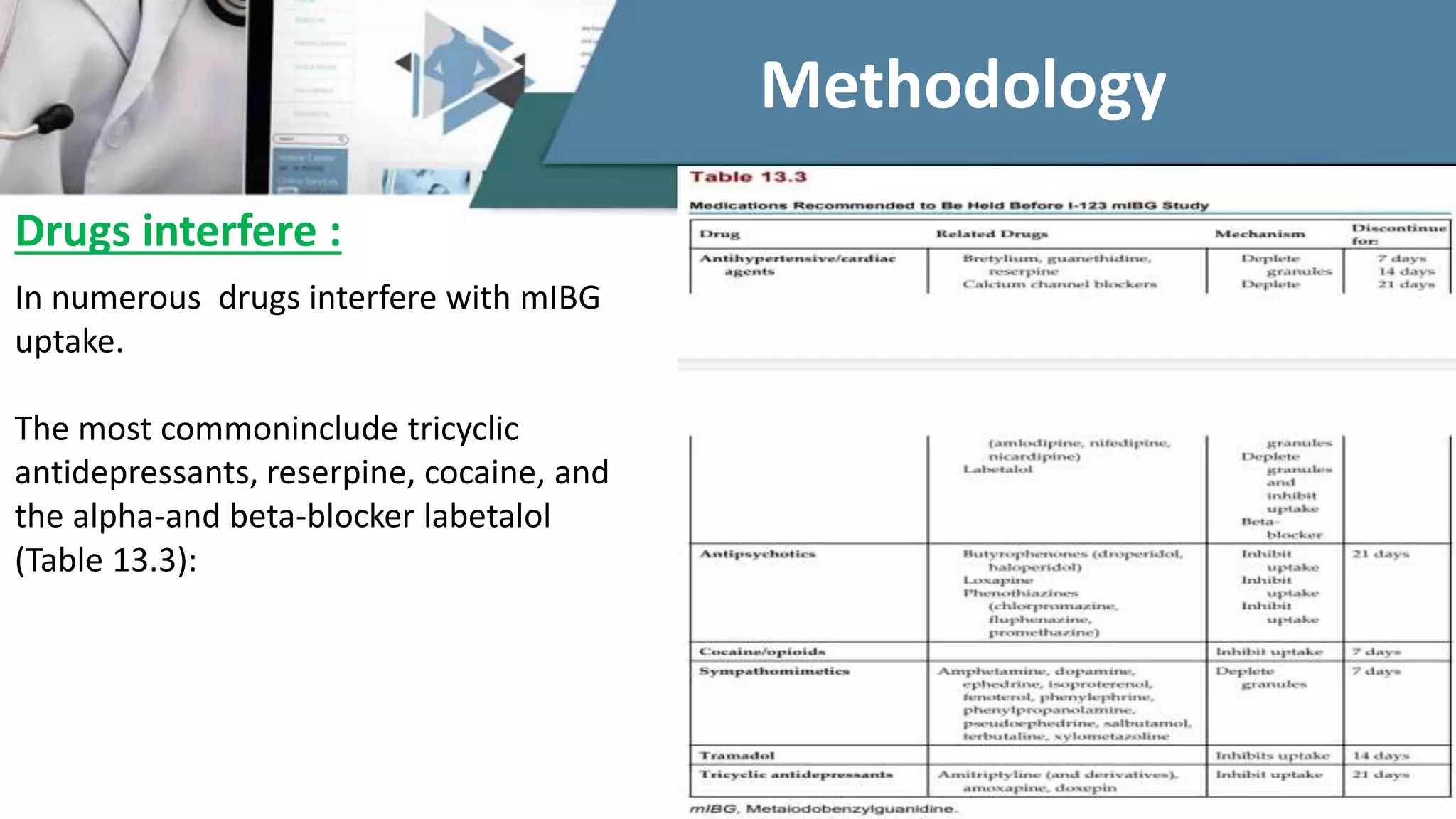

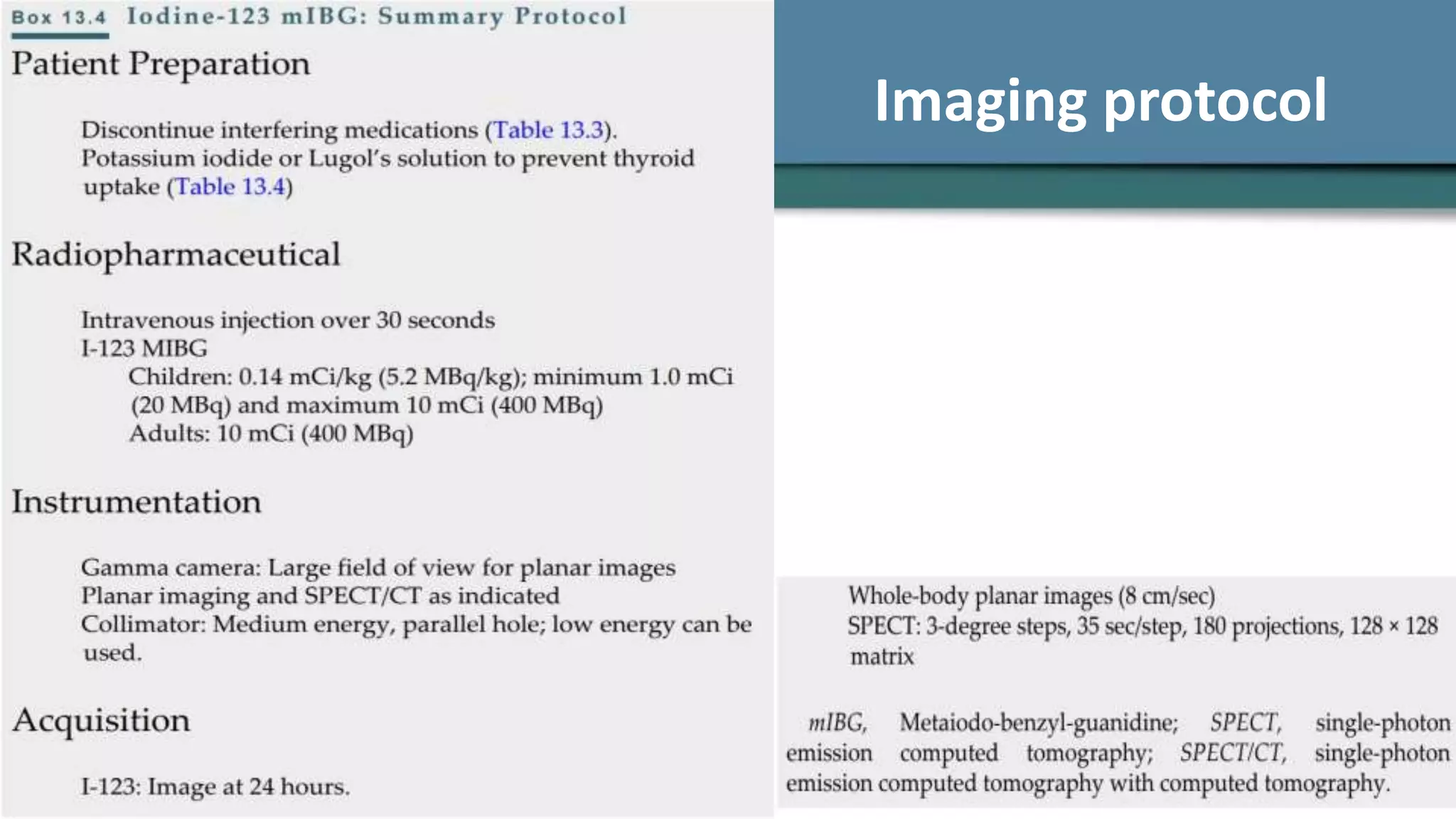

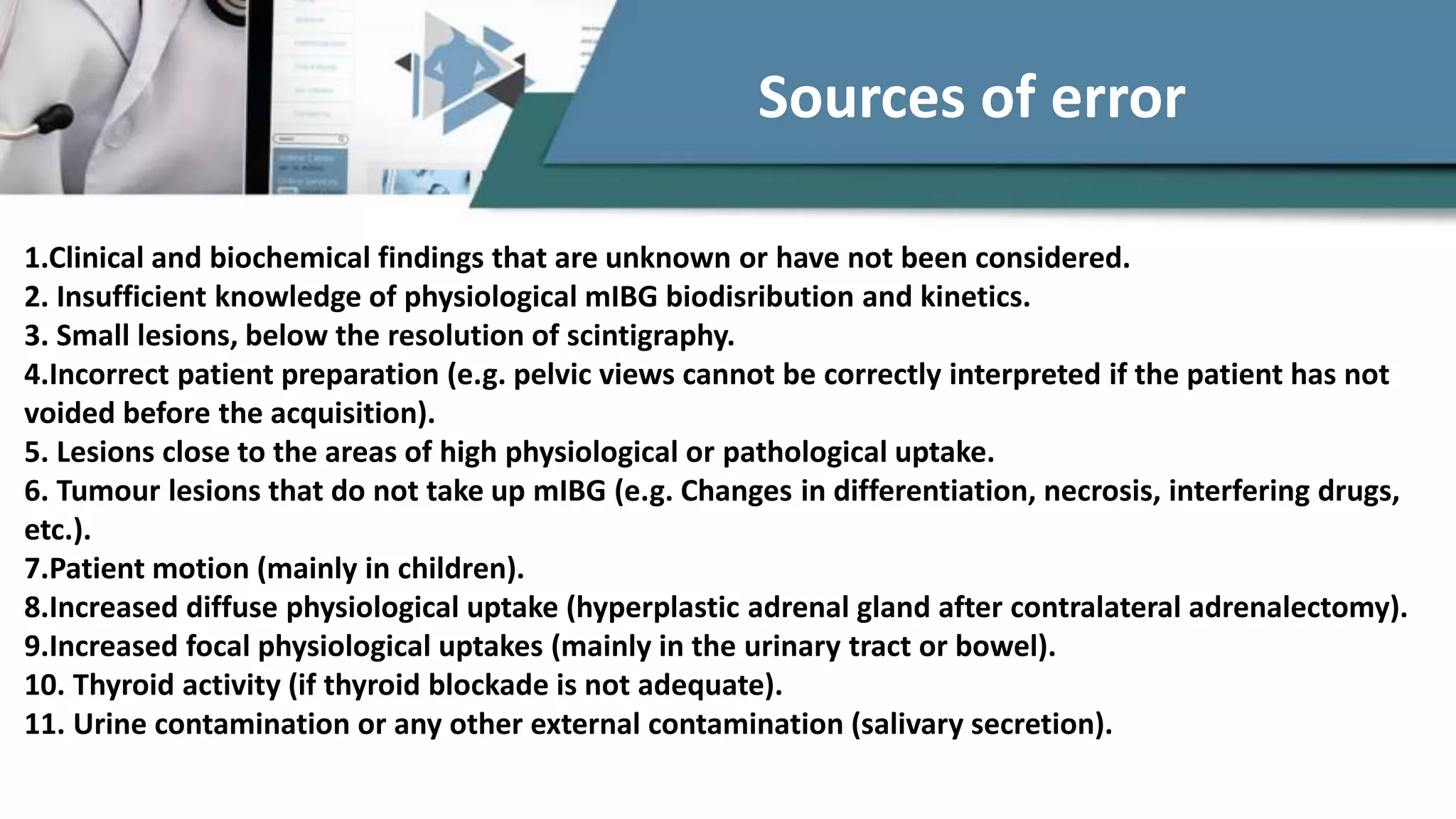

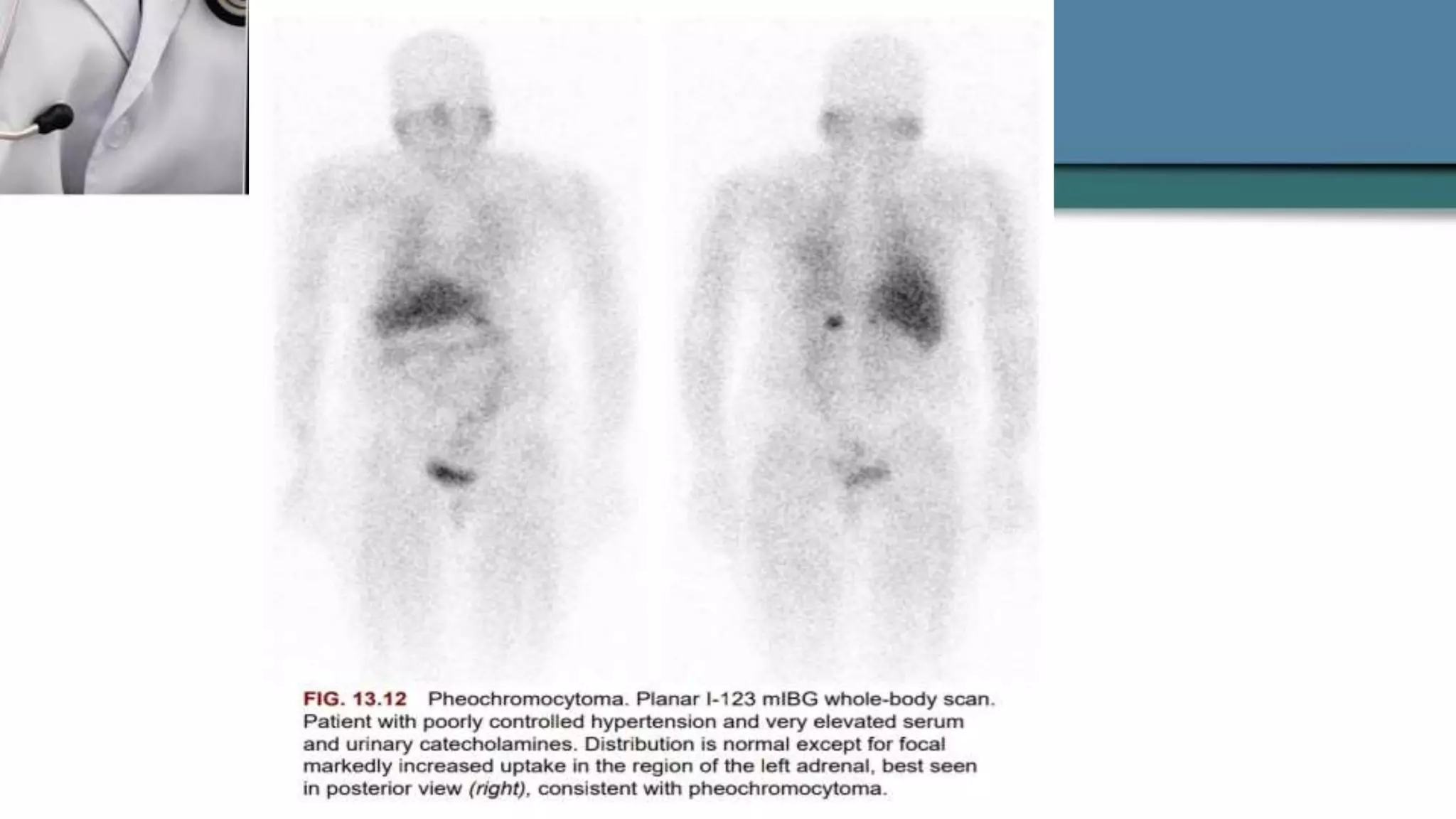

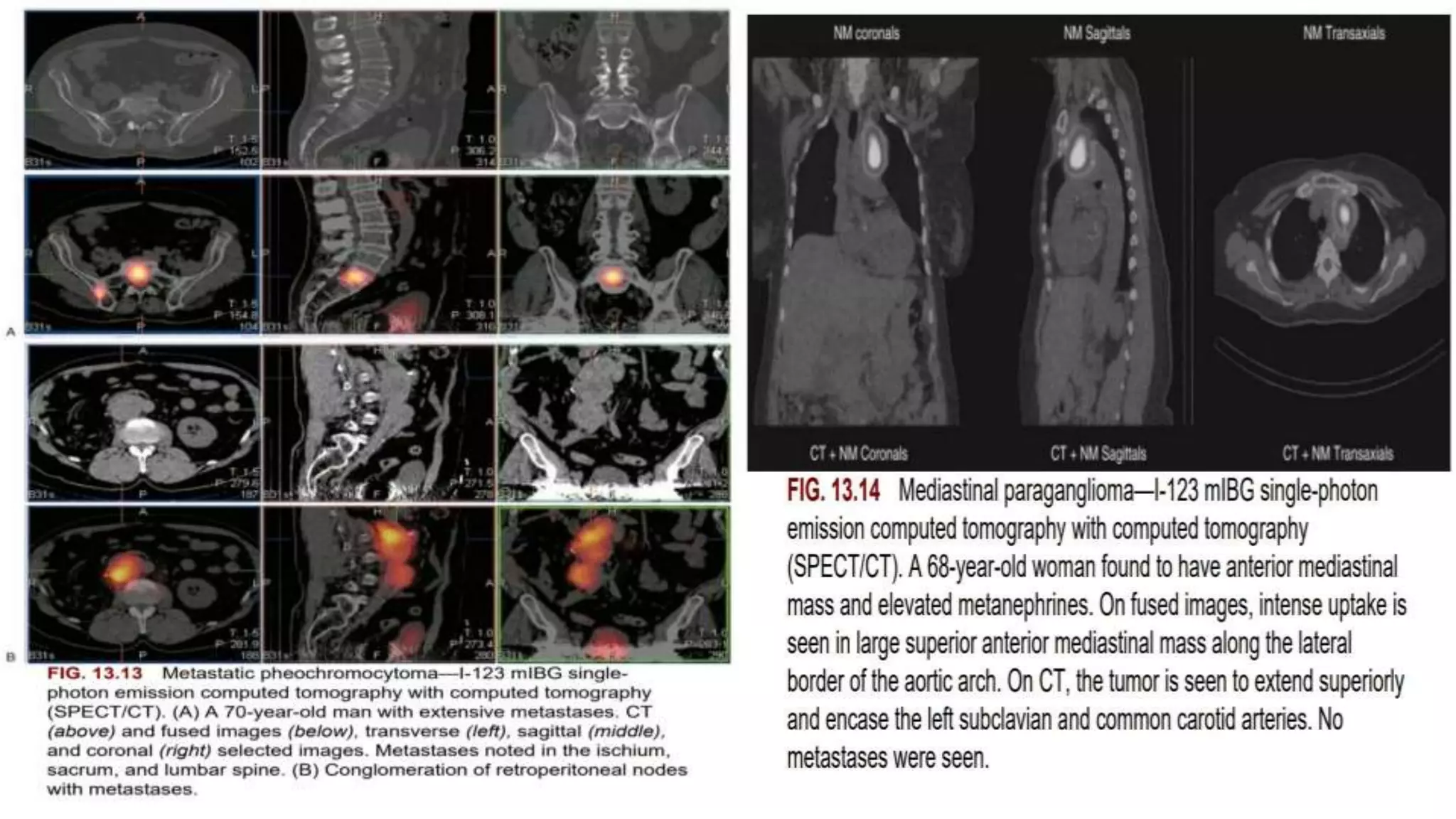

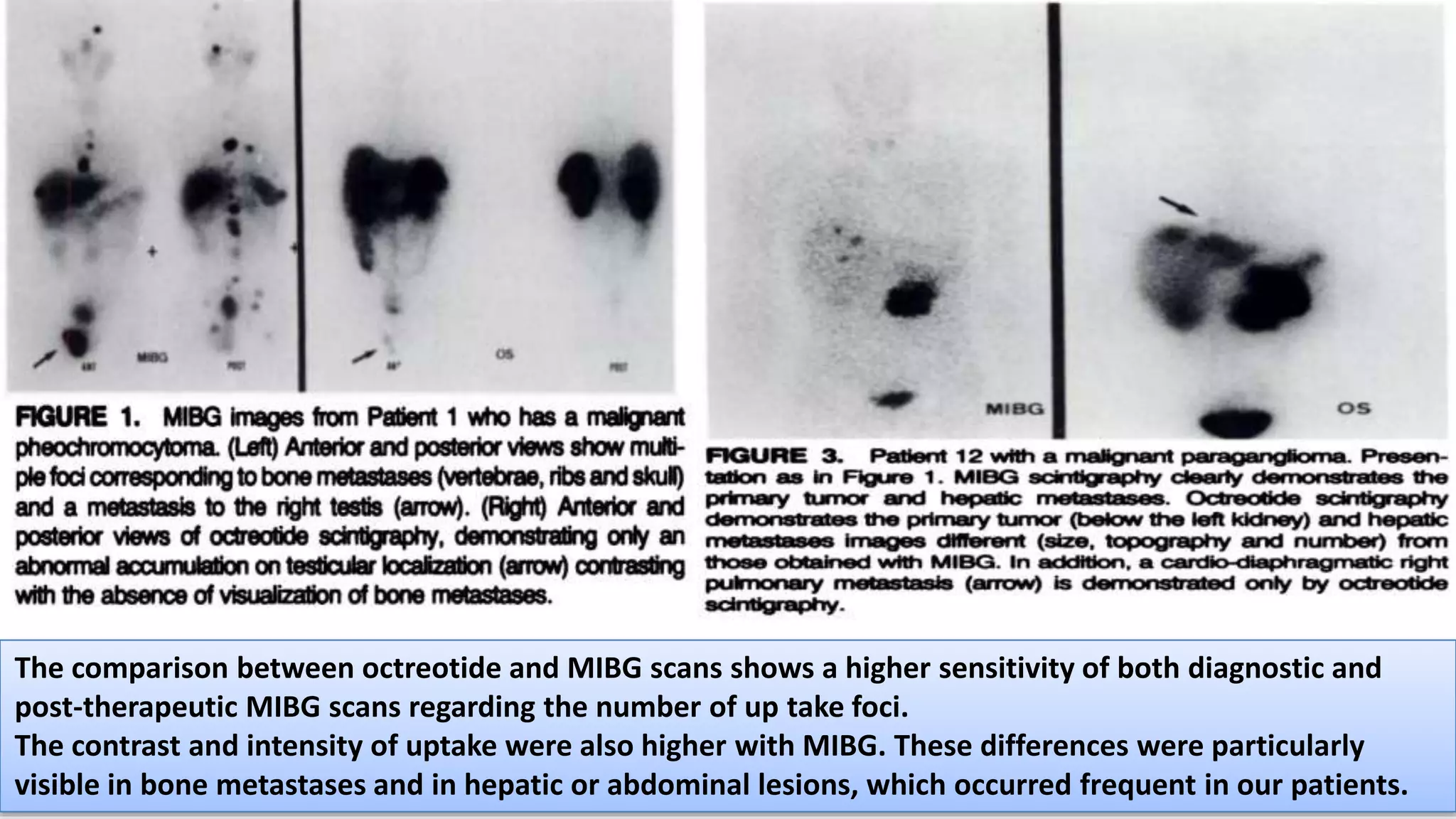

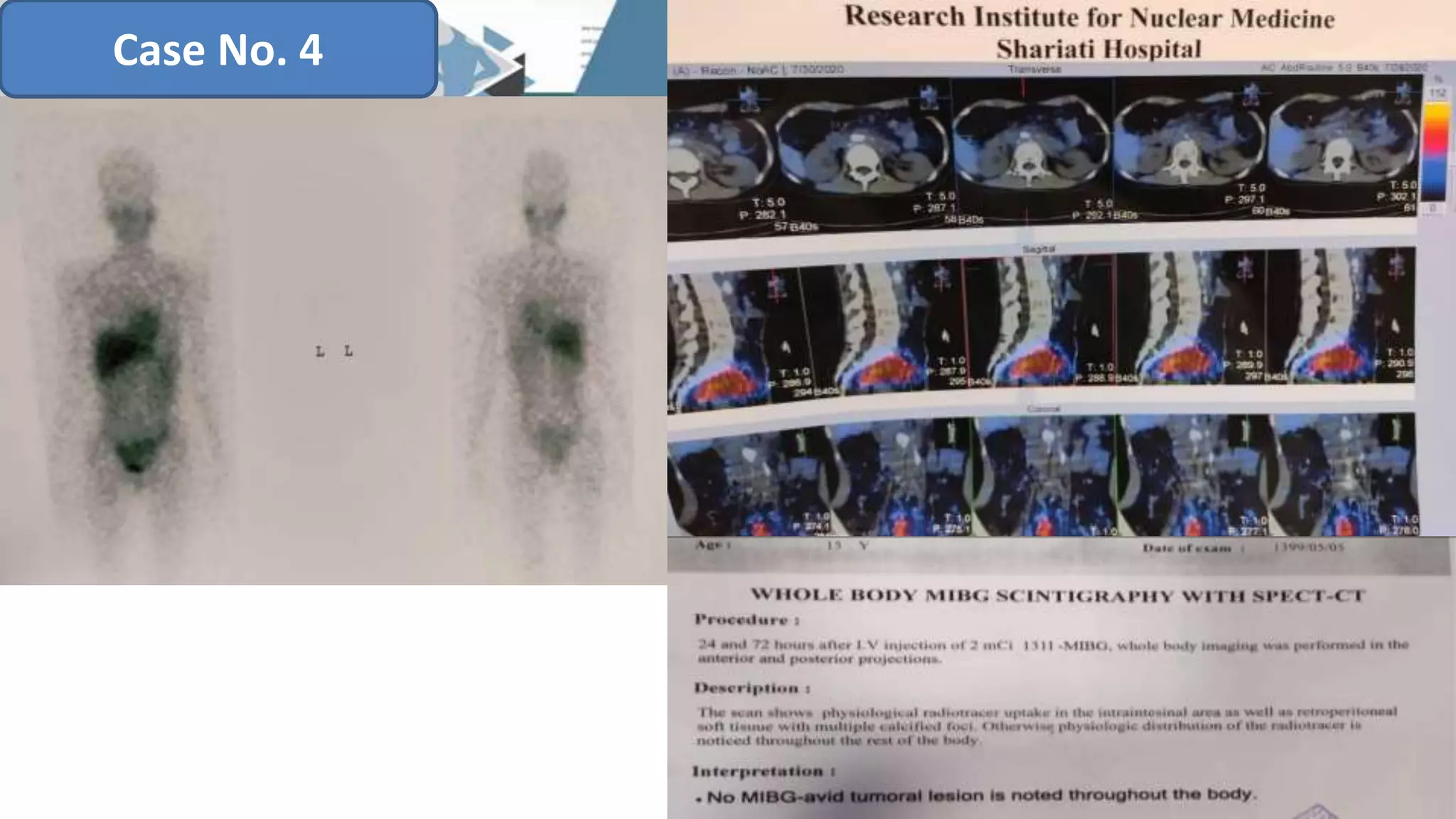

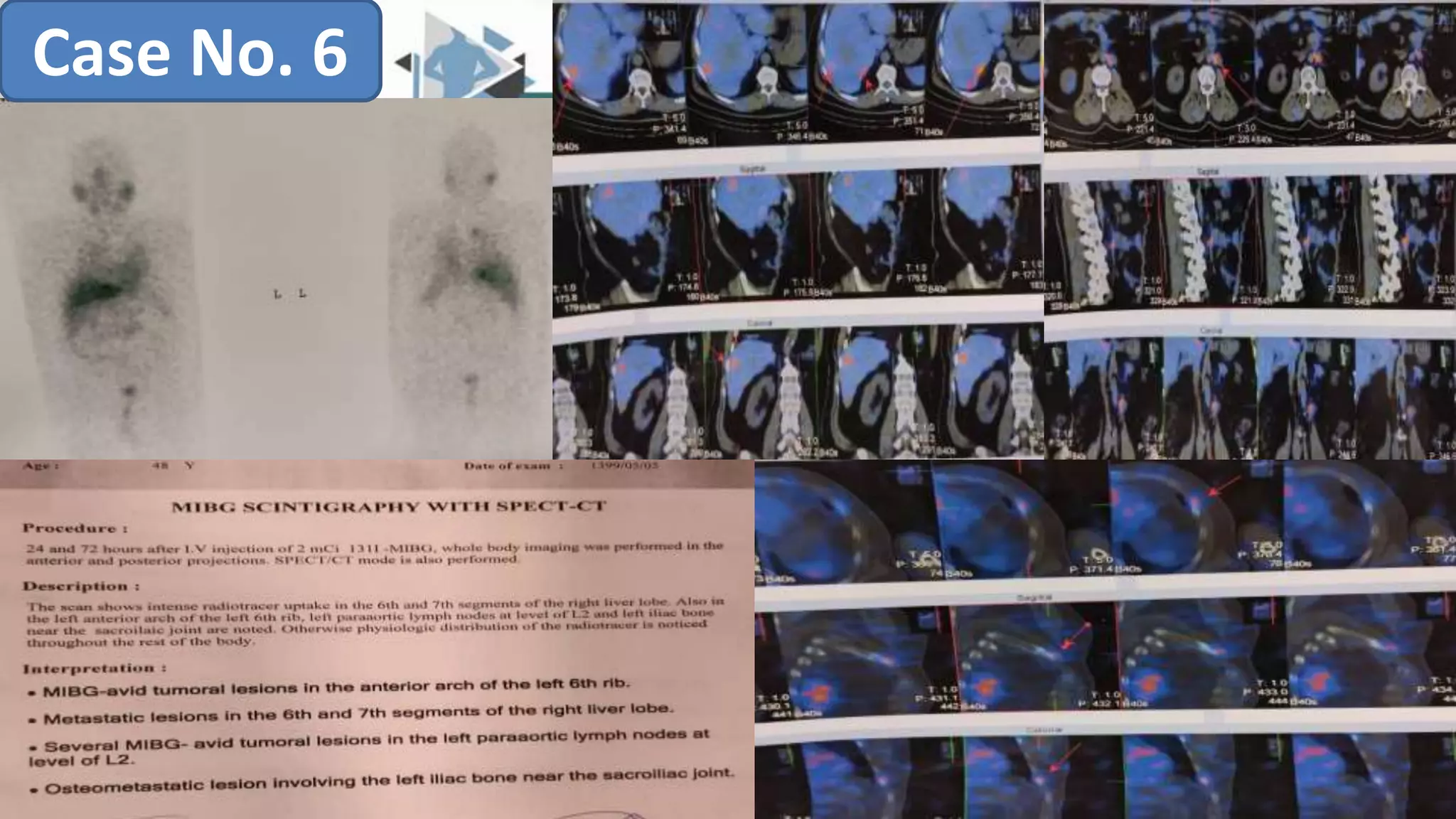

The document discusses the clinical applications and methodologies for using i-123 and i-131 MIBG in the imaging and treatment of neural crest tumors such as pheochromocytomas and neuroblastomas. It highlights the advantages of i-123 MIBG over i-131 in terms of image quality and patient safety, details the interference caused by certain drugs, and outlines baseline methodologies and evaluation criteria for effective diagnosis and treatment. Additionally, it mentions the FDA approval of iobenguane i-131 (Azedra) for treating advanced cases and the preparation protocols required for patients before MIBG therapy.