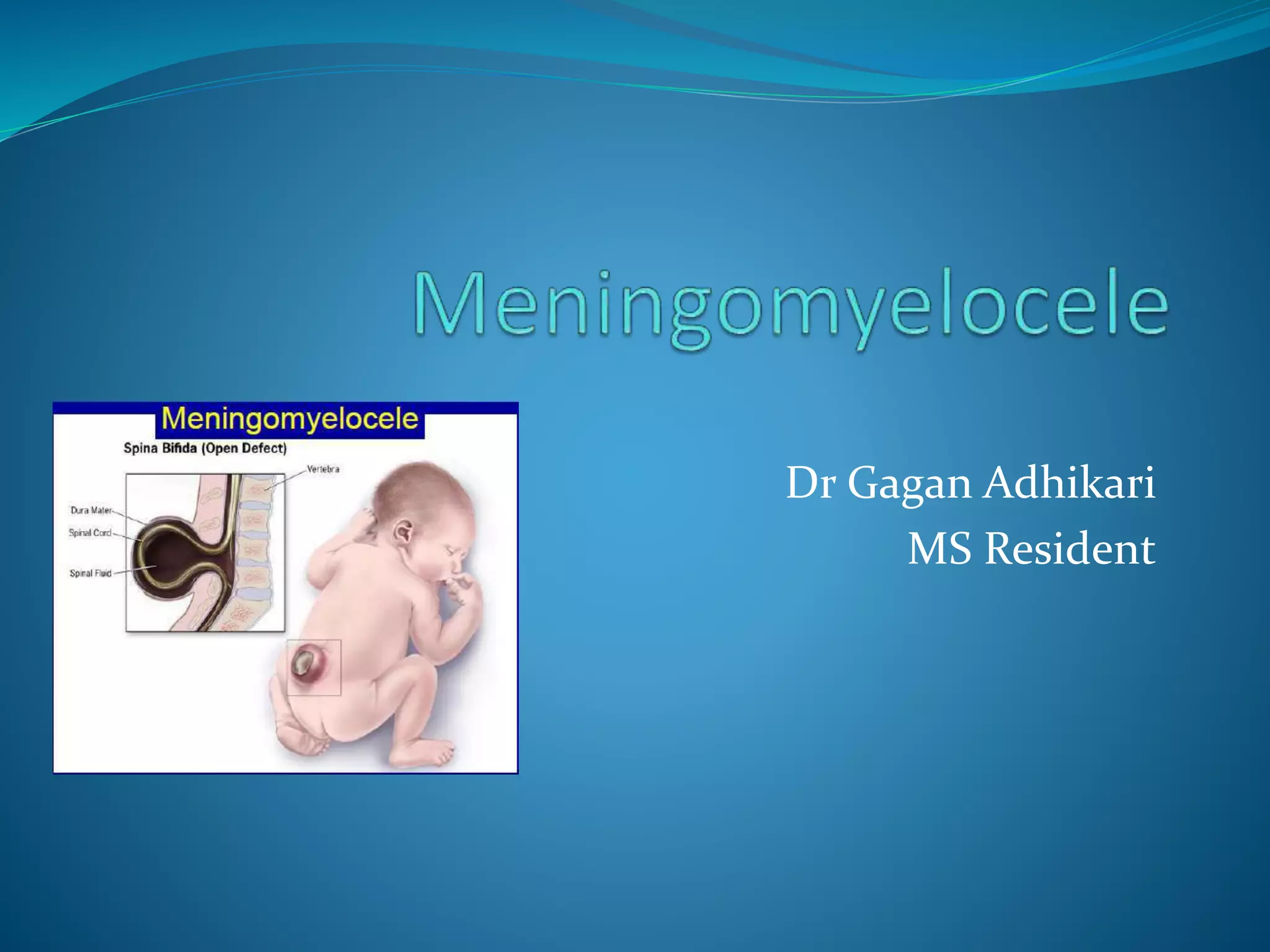

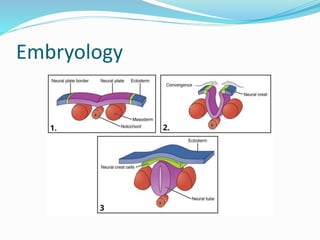

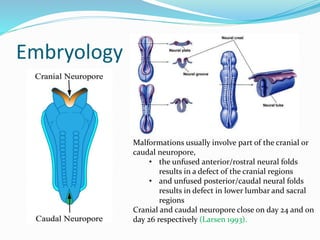

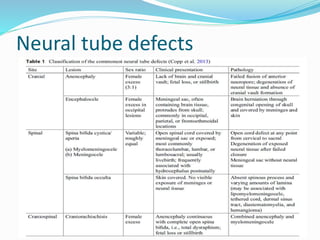

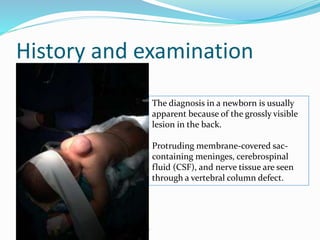

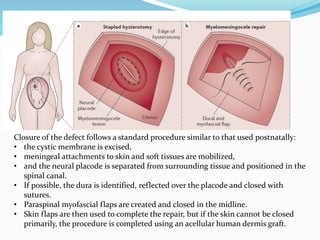

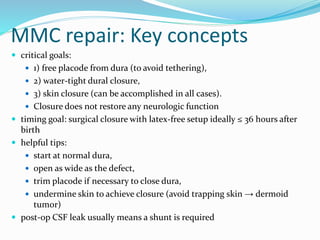

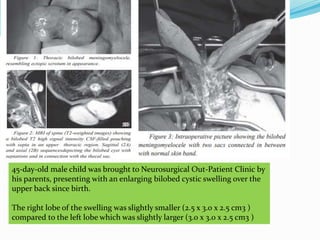

Neural tube defects are caused by abnormal neurulation, the process of forming the neural tube during the fourth week of development. Failure of the neural tube to close properly results in malformations like myelomeningocele, where the meninges and spinal cord protrude through an opening in the vertebrae. Prenatal diagnosis allows parents to make informed decisions and improves care for affected newborns. Common features include paralysis, bladder/bowel issues, orthopedic problems, and hydrocephalus.