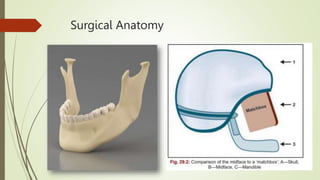

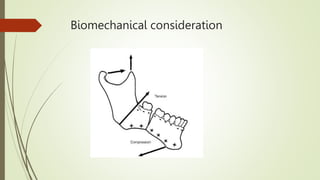

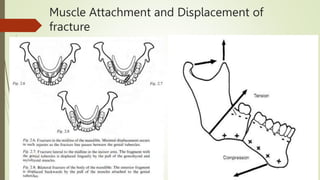

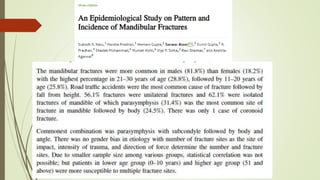

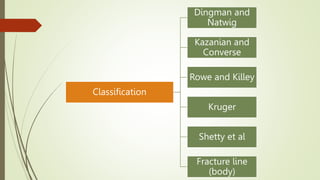

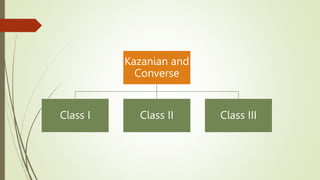

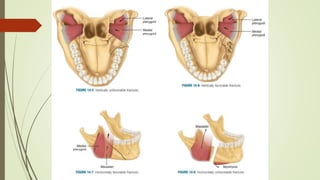

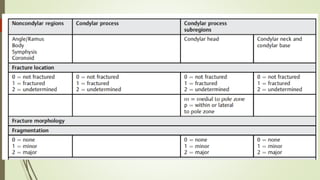

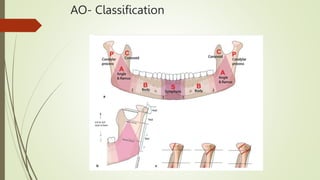

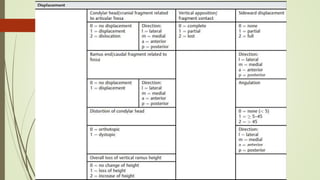

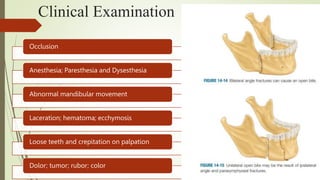

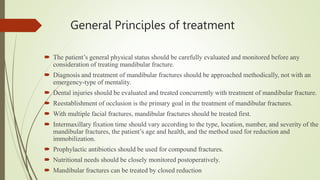

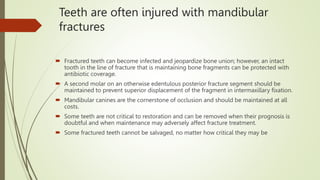

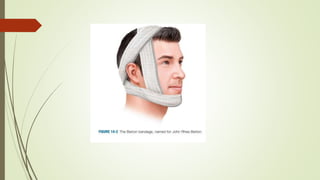

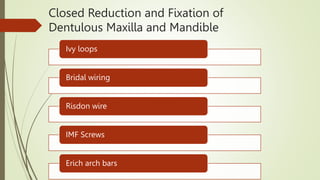

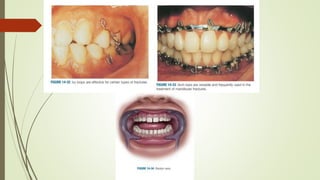

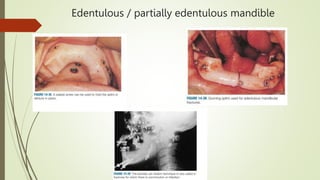

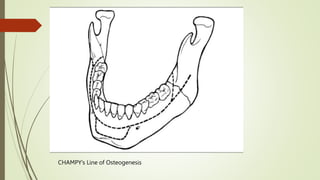

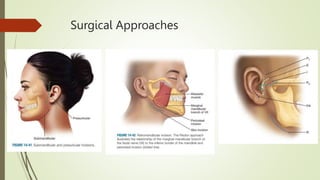

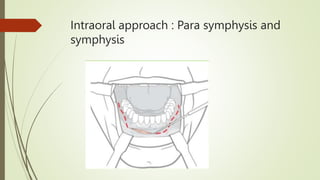

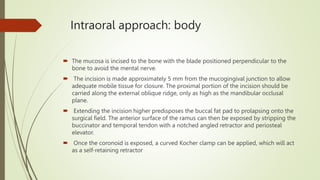

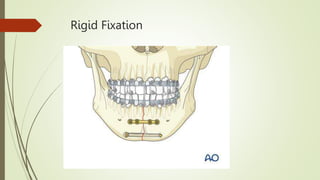

The document discusses mandibular fractures, including the most common site being the parasymphysis. It covers surgical anatomy, classification systems, diagnosis, treatment approaches like closed or open reduction, and complications. Treatment involves reestablishing occlusion through methods like intermaxillary fixation or rigid fixation for displaced fractures. Infection is the most common complication, ranging from 5-10%, and treatment approach, fixation technique, and surgeon experience can impact complication rates.