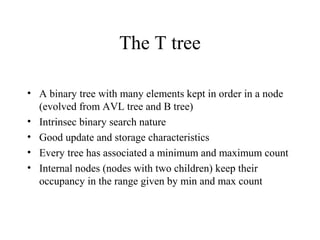

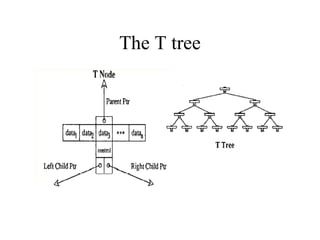

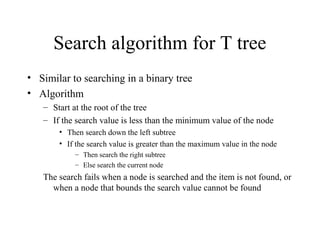

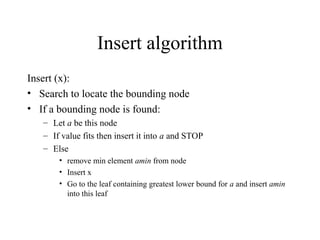

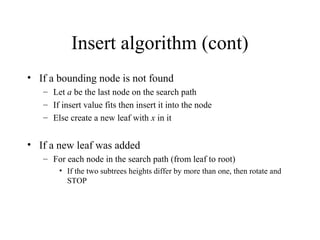

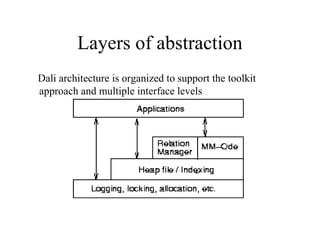

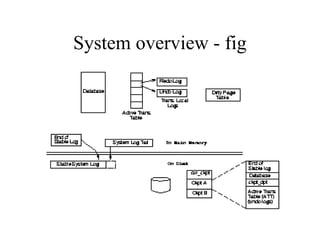

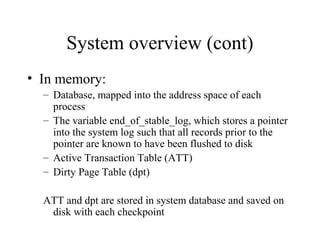

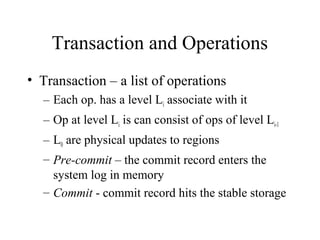

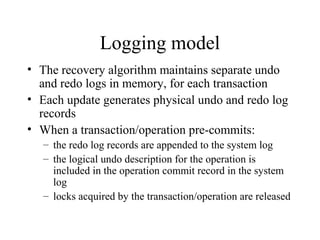

Main Memory database systems store data primarily in main memory for faster access compared to disk-based systems. The T tree is proposed as an index structure for main memory databases that provides fast search, insert and delete performance while using relatively little memory space. The Dali storage manager is designed for main memory databases and provides persistence, availability and recovery guarantees similar to disk-based databases through the use of logging, locking, checkpointing and other techniques while leveraging the speed of main memory.