This document discusses cell coverage and ranges for LTE networks. Key points include:

- LTE aims to support cell radii up to 5 km while still enabling coverage of 100km or more, to support high-speed rail and wide-area deployments.

- Cell sizes in LTE can range from a few meters across in indoor environments to radii of 100km or more for large rural cells.

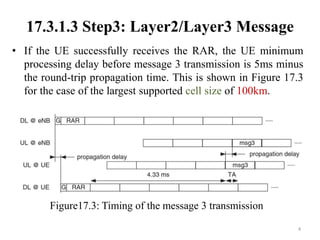

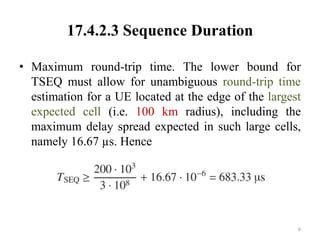

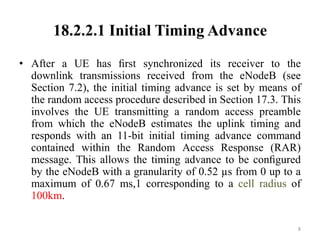

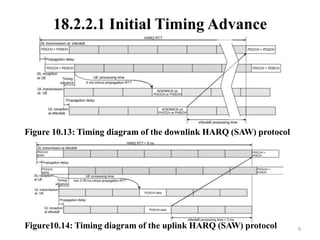

- The random access preamble formats and timing advance mechanisms in LTE are designed to support the maximum cell size of 100km radius to accommodate the largest expected propagation delays.

- A guard period duration of 700 μs supports one-way propagation delays of around 100km, allowing LTE to potentially support cell