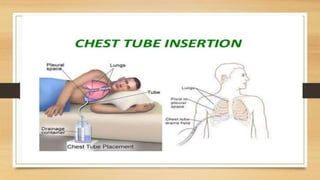

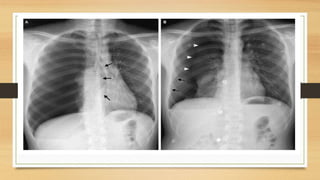

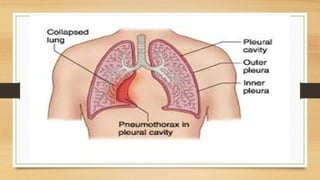

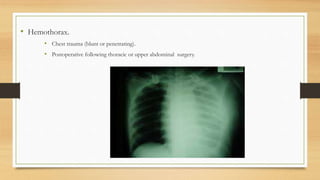

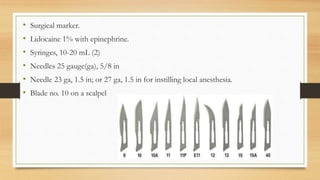

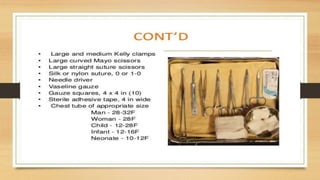

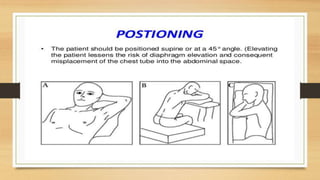

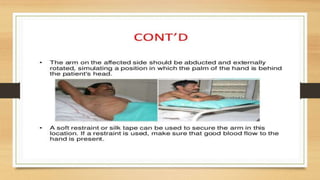

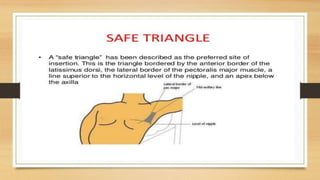

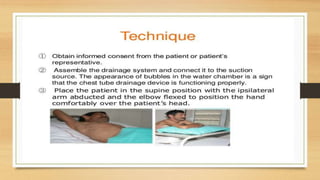

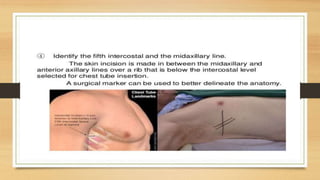

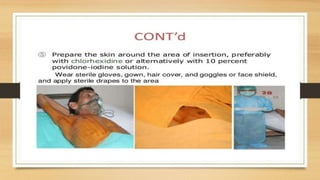

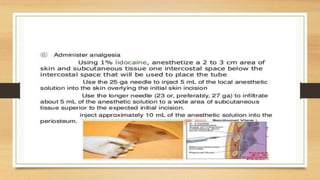

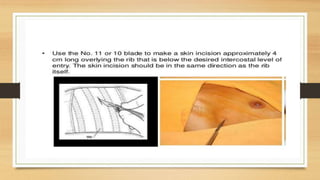

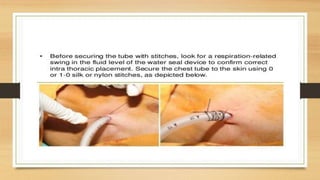

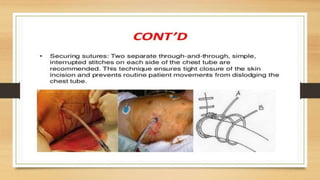

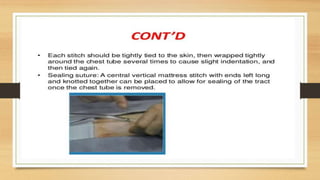

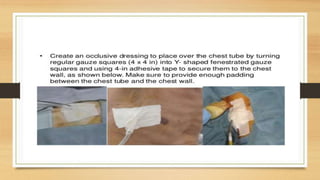

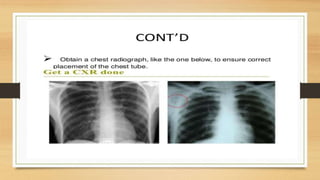

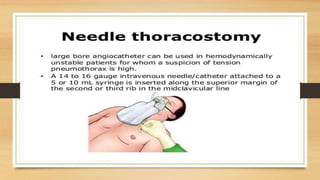

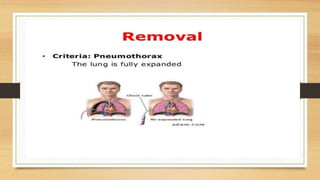

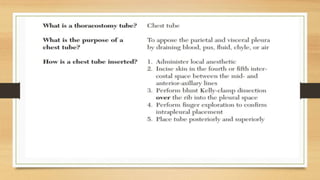

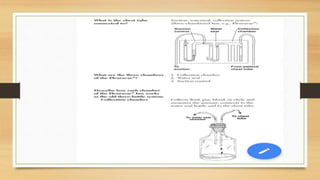

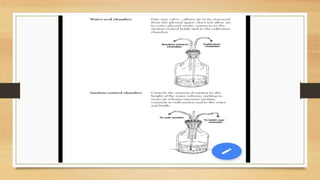

This lecture covers chest tube insertion, including its definition, indications (such as pneumothorax and hemothorax), contraindications, preparation, techniques, and potential complications. It emphasizes the importance of proper equipment, technique, and management of complications during and after tube placement. Additionally, it highlights guidelines for antibiotic prophylaxis and careful monitoring of patients post-procedure to avoid complications like re-expansion pulmonary edema.